By GARRET JAROS/YachatsNews

Tumbling down from the highest mountain in the Coast Range to the edge of the Pacific Ocean is the Siuslaw National Forest – a verdant landscape that backdrops Lincoln County communities which rely upon it for recreation, water and timber.

For years the coastal forest has been managed to protect older trees that harbor fish and wildlife threatened with extinction while allowing thinning of younger trees from timber plantations.

A comprehensive new look at how the forest is managed may bring changes and that has conservation groups like the Coast Range Association mobilizing to educate the public about what is at stake.

Guidelines for managing millions of acres of forestlands in the Pacific Northwest – including the 630,000-acre Siuslaw forest — are changing for the first time in decades as the U.S. Forest Service prepares to amend its 1994 Northwest Forest Plan.

Evolving “ecological and social conditions” are challenging the effectiveness of the plan, the agency said when announcing the amendment process in December.

Collaborating to draft the amendment is a Federal Advisory Committee tasked with integrating scientific studies, assessments and monitoring reports compiled over the last 30 years. The committee is supposed to consider climate change, fire danger, conservation of mature forests and riparian habitats, Indigenous knowledge, and timber and non-timber forest resource sales that help sustain rural communities.

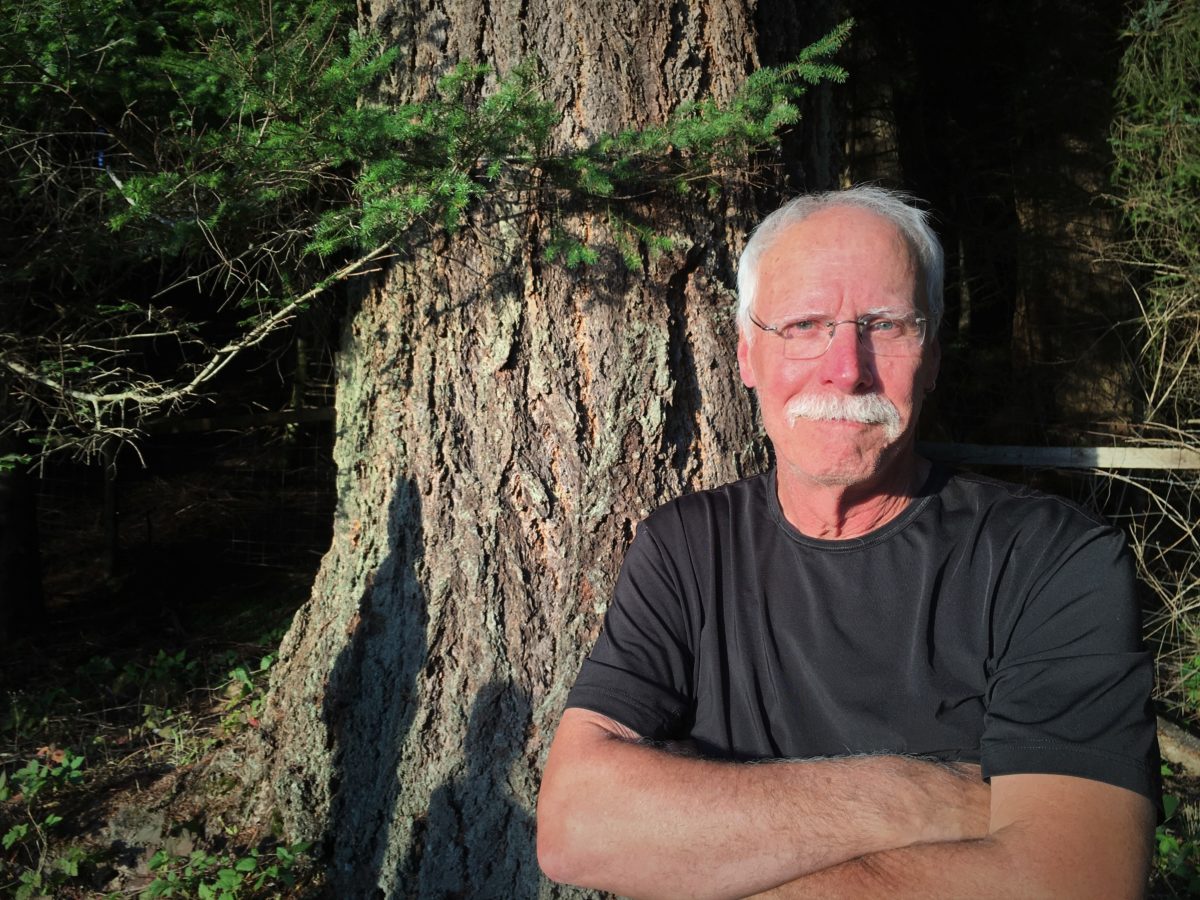

Coast Range Association co-director Chuck Willer of Corvallis is concerned language used in the reasons for the amendment – like “climate change” and “wildfires” – may be nothing more than a smokescreen for increasing logging of federal forests.

“The Forest Service amendment process may open the door to the loss of protection for streams and mature forest within the Siuslaw National Forest,” the association says on its website. “The timber industry will be in high gear to influence the amendment process. We know that several large mills will do everything in their power to open the Siuslaw National Forest to cutting mature forest.”

The advisory committee includes scientists, state, county and tribal representatives, forest products industry representatives, conservation organizations, wildlife advocates, outdoor recreation groups, forest collaborative groups and watershed management organizations.

A draft environmental impact statement outlining the amendment was planned for late June but that has been delayed until “sometime this summer,” according to the Forest Service. Once it is released the public will have 90 days to comment. A final version is expected in October — but it too could be delayed.

Northwest Forest Plan

The Northwest Forest Plan was enacted in 1994 to protect the northern spotted owl and the old-growth forests it relies upon for survival. The owl, an indicator species for the overall health of those forests, was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act in 1990. At that time, overlogging was identified as the primary cause for the owl’s rapidly decreasing numbers.

A series of policies and guidelines comprise the plan, which governs 24.5 million acres of federal lands in Oregon, western Washington and northwestern California – including 19.5 million acres on 17 national forests.

With the goal of protecting the long-term health of forests, wildlife and water, a multidisciplinary team of scientists in the early 1990s identified management alternatives to meet applicable laws and regulations for endangered species, clean water, forest management and land use.

The plan also had to account for a 1960 law that directs the U.S. Department of Agriculture to manage national forests by providing a sustained yield of timber and non-timber forest products without “impairment of the productivity of the land” while equally providing for recreation.

The Northwest Forest Plan was eventually broadened to protect more wildlife and its associated habitat — including the endangered marbled murrelet and threatened and endangered coho salmon – and was intended to last 100 years.

Lands managed by the plan include 79 percent of 17 national forests encompassing 19.4 million acres in three states; 11 percent of seven Bureau of Land Management districts encompassing 2.7 million acres; 9 percent of six national parks encompassing 2.2 million acres; and 1 percent of national wildlife refuges and Department of Defense Lands encompassing 165,000 acres.

Why amend now?

Despite protections, the number of spotted owls has continued to decrease across the Northwest. They remain listed as threatened on federal lands but are listed as endangered on state lands managed by the Oregon Department of Forestry. In southwest Canada they are nearly extinct.

The Forest Service says encroaching barred owls are now a primary factor affecting the number of northern spotted owls as is continued habitat loss from logging, wildfire, insects and disease. The agency added that “ecologically appropriate timber management, such as thinning, can contribute to development of new habitat.”

“Thirty years (after the NWFP was enacted), this landscape has experienced significant social, economic, and ecological changes,” according to the Forest Service. “Amending (it) will provide an updated management framework that incorporates best available scientific information and current conditions.”

Leading up to the decision to amend the forest plan was a 2011 recovery plan for the owl, a 2012 critical habitat designation and a 2021 revision of that designation. In 2021, President Joe Biden issued Executive Order 14008 directing the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Forest Service, and the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the BLM, to prioritize action on climate change in policymaking and the budget process.

It called for protecting older forests but emphasized that public lands, waters and financial programs support climate action in part by “providing an immediate, clear, and stable source of product demand,” increased reforestation, resilience to wildfires and jobs. And called for conserving 30 percent of lands and water by 2030.

Then in 2022, Biden issued Executive Order 14072, which also addressed climate change and wildfires through forest health and restoration “and other nature-based solutions to improve resiliency in the face of increasing disturbances and chronic stress…”

The order called for “conserving old-growth and mature forests on federal lands while supporting and advancing climate-smart forestry and sustainable forest products.” It also emphasized the multi-use mandate of recreation – camping, hiking, hunting and fishing – to help “local economies thrive.”

Siuslaw National Forest

The Siuslaw National Forest is a temperate rainforest stretching from Tillamook to Coos Bay. It covers parts of eight counties and boasts 30 natural lakes and 1,200 miles of rivers and streams that are home to more than 200 species of fish, 235 bird species, 26 amphibian and reptile species and 69 species of mammals.

It is managed in accordance with the forest plan and is home to northern spotted owls, marbled murrelets, red tree voles, salmon and steelhead.

While the Forest Service manages to protect habitat, it is the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife that manages fish and game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration that track species recovery.

Whether coho, chinook and steelhead numbers are up or down on the Siuslaw is not easy to say because it depends on the river basin where they end and begin their lives, said ODFW mid-coast fishery biologist John Spangler. It is the ocean that really determines their abundance, he added.

“Given all the environmental issues going on with climate change and everything, we are seeing some downturns in some basins on chinook, and on some within the national forest they are improving,” Spangler said. “With coho, they seem to be doing pretty good. But with steelhead, the ocean was really poor so the last four or five years it’s been poor returns. But this year it was a very good return.”

The Siuslaw is gaining older forests with more intact watersheds, Spangler said, so they are just functioning better and “as nature would intend them to function.”

“They seem to have more wood so therefore better fish production,” he said.

Efforts to restore salmon habitat on the Siuslaw have been steady according to forest managers. Since 2020 more than 1,300 logs have been placed in 28 miles of coastal streams to improve salmon habitat. Five barrier culverts have been removed and replaced with better passages, and more than eight acres of riparian habitat have been planted with conifer and native hardwoods.

Tracking the numbers of northern spotted owl on the Siuslaw is also difficult and ODFW does not have forest-by-forest numbers, said the agency’s threatened and endangered species coordinator

There has been an increase in owl habitat in older stands of trees on the Siuslaw, the agency’s staff wrote in an email to YachatsNews. And there are “many pockets of century old trees” mostly at the bottom of drainages or in places not prone to fire.

“But overall populations of the northern spotted owl have decreased regionally,” they said. “Work will continue to address not only the age but functionality of future habitat.”

About 60 percent of the trees on the Siuslaw are estimated to be 100 to 140 years old. In keeping with the forest plan, Siuslaw managers have focused on leaving those trees standing to provide wildlife habitat.

“If the NWFP amendment changes age limits or diameter recommendations, we will follow those new guidelines,” staff wrote.

On average, the Siuslaw sells 40 million board feet of timber each year through “restoration thinning projects” in younger plantation stands. In 2023, it sold 46 million board feet.

“For many years, the Siuslaw National Forest has focused on managing timber plantations to create late successional reserve forest conditions,” Katie Richarson, the Siuslaw’s natural resources staff officer said in an email to YachatsNews.

“After the Northwest Forest Plan amendment, we hope to identify additional areas where management might help reduce fire risk or adapt the landscape to climate change, but these areas are not likely to contain old growth and would be subject to additional environmental analysis and public comment.”

Coast Range Association

In order to raise awareness about the amendment and its possible impacts, the Coast Range Association began holding educational meetings in coastal communities beginning in Yachats in April.

“We have two goals,” Willer said. “Educating people about the amendment process and explaining things about the Siuslaw National Forest so they can provide input to the Forest Service when the time comes. The Siuslaw is unique in terms of fire ecology because it’s a coastal forest … so a lot of the story that gets told about fire does not apply to the Siuslaw.”

By mid-May nearly 100 people had formed three groups on the north, central and south coast to begin “ground-truthing” the inventory of trees listed on Forest Service maps. They are identifying random, select mature forests to visit, photograph and document, Willer said.

“I think (the Forest Service) has a commitment to thinning 40 percent of the forest that’s been managed,” Willer said. “And they over-thin in my opinion. And if they do too much of that in a short period of time, it would not be good for the forest. It would open up way too much of the forest to drying out with air.

“It is an agency with one tool – a hammer, and all problems are the same nail, to cut trees in some way,” added Willer, who is also part of a collaborative group comprised of conservationists and timber industry people.

Willer also expressed concern about transparency from the Siuslaw National Forest, saying they do not give out detailed information to the public unless they submit a Freedom of Information Act request, which “really puts a roadblock in front of normal people.” He added that the dissemination of quite a bit of information depends on staff approval in Portland.

“That is a very scary policy,” Willer said. “Working staff have been told not to talk to the public, that the public needs to go through proper channels. This all harkens back to the timber wars of an earlier era — the circle the wagon ’80s. It says to me the Trump administration really rolled back some institutional behavior. And it doesn’t seem to be a priority for the Biden administration to figure it out and loosen things up. Or it works for their interests.”

- Garret Jaros is YachatsNews’ full-time reporter and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com

To stay informed on the Northwest Forest Plan amendment go to the Forest Service’s website here

the best way to grow healthy forests in the coast ranges is with animal based organic fertilizer on the national forests and national parks to make the trees grow three times as fast and three times as tall

Thinning and even clear cutting are valid management tools to protect the forests. If you eliminate these tools, or restrict them too much, fire will do much more damage than chainsaws. Clear cuts can make fire breaks in a deliberate pattern, enhancing efforts to protect mature forest. Mature forest without fire breaks results in unstoppable fires burning it all.

The only reason for clear cutting is economic. It’s cheaper. The best way to manage forests for the health of all species and the environment is all-ages multiple species management. Thinning. No clear cutting. Healthy forests, not monocultural tree farms.

Thank you Garret for a well written article. One unique fact about the Siuslaw National Forest that sets it apart from all the others in the region; a low elevation temperate rainforest in close proximity to the Pacific Ocean with intact stands of mature mixed conifer capable of storing more carbon per acre than any forest on the planet.

A lot of folks and groups don’t agree the Barred Owl is responsible for the decline of the Spotted Owl nearly as much as other factors. USFS, and other agencies, current proposal to shoot them is questionable.

When does protecting our water quality and quantity become more important than cutting trees? I’m in favor of thinning deadwood as needed for fire protection but cutting too many healthy, old trees interferes with water quality and quantity and in the long run, that is worse. Thin trees and underbrush but stop cutting down our forests so much.