By LAUREN ELLENBECKER/Columbia Insight

Over a century ago, settlers altered the Pacific Coast’s natural shape with the introduction of two non-native grass species. Now, a new hybrid grass species is making headway, presenting challenges for dune restoration.

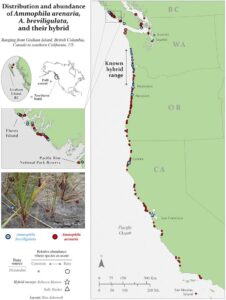

A study published last month in the journal Ecosphere said two invasive, dune-building beachgrasses — European beachgrass and American beachgrass — hybridized to create a new beachgrass taxa, but said “little is known about its distribution, spread and ecological consequences.”

The study was conducted by Oregon State University researchers, who led a large-scale survey along the Oregon and Washington coasts, finding nearly 300 individual hybrids of European and American beach grass.

While documenting the hybrid’s far reach, researchers also found the new grasses were within and near conservation habitats designated for the western snowy plover and streaked horned lark, both listed under the Endangered Species Act.

The findings built off a 2021 discovery of only a dozen hybrid sites along the coast. The hybrid was first observed in 2012.

“It creeped up on us. You would never have thought of hybridization being a likelihood,” says Sally Hacker, an OSU coastal ecologist and one of the study’s co-authors. “It all happened in this intentional yet unlikely way.”

European beach grass has thin blades that help create tall and narrow dunes. Its rhizomes can shoot upward, allowing the hardy clumps to keep pace with towering sand.

American beach grass slightly differs, growing fewer thick stalks to form short, wide dunes.

Where the two overlap, hybrids may appear and outshine the parent species by being both tall and wide, says Hacker.

Of further concern, hybrid beach grass could crossbreed with European and American beach grasses, allowing genes to flow between the invasive species — fueling their dominance along the coast, competing with native species and making beaches narrower.

“They’re everywhere,” says Hacker. “They’re going to be exponential in abundance.”

Two-state study

The Oregon and Washington shorelines were originally only sparsely dotted with vegetation.

Sand moved freely along expansive, low-lying plains similarly to a river, according to Celeste Lebo, a regional habitat restoration biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The landscape was constantly transforming under wind and tidal influences, untethered by masses of grass.

Native vegetation shaped lower dunes that melted and swelled under the wind’s push and pull. These plants became accustomed to seasons of being completely buried, only to flower again and reproduce.

But the coast’s original openness wasn’t conducive to the modern human lifestyle.

Fine particles of sand would slowly accumulate along a home’s window frames, on the porch and between cracks.

Without a barrier to break the wind, sand could engulf an entire house, sometimes piling up to its roof and cracking weak points under its weight, according to Meg Reed, a Newport-based Oregon coastal policy specialist with the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development.

Beginning in the early 20th century, settlers planted European beachgrass near Florence to serve as a windbreak, a practice the U.S. Forest Service oversaw years later.

Shortly after, American beach grass, native to the East Coast and Great Lakes, debuted along the Clatsop Peninsula near the mouth of the Columbia River.

By the 1950s, nonnative beach grasses had spread from Mexico to Canada.

“When this change happened, with this planting of nonnative grasses, it just totally changed the landscape and made it difficult for native species to compete,” says Reed.

The beach grasses’ invasion of the Pacific Coast is permanent.

This year, the Washington Noxious Weed Control Board classified European, American and hybrid beach grass as a “Class C” weed, a designation that reflects the species’ invasive nature without requiring control. A listing, however, can help local organizations, governments and agencies acquire funding for beach grass management.

Dune restoration

Lebo says mending dunes is a relatively new area of focus, as opposed to rehabilitating estuaries and coastal prairies.

Pacific Coast dune restoration thus presents novel challenges — this is an area of focus that remains largely unexplored — as environmental managers attempt to keep pace with an endlessly morphing landscape.

Restorative efforts by public and private entities are nevertheless scattered across coastal communities in Oregon and Washington.

These include a large dunes restoration undertaking led by the Siuslaw National Forest on the central Oregon coast by a coalition of stakeholders including federal, tribal, state and county agencies, watershed councils, recreation groups and environmental groups.

Beach grass management can involve scraping away invasive grasses with mechanical equipment, spraying them with herbicide or prescribing burns.

Practices can be more intensive, involving digging a trench the width of a bulldozer, tearing beach grass off the top, burying it and smoothing the surface.

Management efforts can be indiscriminate, leaving a lasting impact on all plants within treated areas, regardless of native origin. Invertebrates residing in wet sand can be smothered when freshly dug material is placed on top of them.

Even further, studies illustrate that snowy plovers can require a 100-foot radius surrounding their nest to feel comfortable. The tiny birds collect shells, driftwood and various beach scraps to make their home, a process easily disrupted by human disturbances.

An issue for homes

Habitat experts such as Lebo hope to centralize coastal dune restoration within one concept.

“How do we restore natural dune processes in ways that are self-sustaining?” she asks.

The Oregon Coastal Dune Partnership, which Lebo helps spearhead, aims to restore the Oregon coast’s native dunes and the species that depend on them.

Partnership members have returned to documented sites in the dunes where native plant communities or rare plant species were known to occur. She says they either can’t find them, or find the habitat degraded by invasive beach grasses, leading them to wonder whether remnant patches of native plants can persist.

“At this point, we’re recognizing that we’re way behind in conserving species that are dependent on natural dune ecosystems,” says Lebo.

Nearly 45 percent of Oregon and Washington’s coastline is composed of beaches and dunes and, among them, a string of small communities.

Foredunes — low hills formed parallel to the ocean edge consisting of sand and driftwood and usually capped by European beach grass — are common along the coast.

Modern life on the coast depends on these sandy walls, which spare residents from the torment of sand dirtying streets or damaging homes during winter storms.

Environmental managers seek to balance tradeoffs that foredunes present, including restoring dunes to support biodiversity versus protecting coastal development by prioritizing beach grass, says Rhiannon Bezore, a LCDC coastal shores specialist.

With help from an OSU doctoral student, Oregon is readying an update to its coastal guidebook, a task last done in 1989. In doing so, it hopes to provide coastal residents with best practices for tending to the dunes in their backyard, including what types of vegetation they can plant.

The Oregon Coastal Dune Partnership and other groups will continue to apply for research grants and explore uncharted territory.

“There’s a lot we just don’t know,” says Lebo, adding this is what makes this realm of study so important.

- Columbia Insight is an online independent, environmental news publication and 501(c)3 nonprofit organization based in Hood River.

It’s important for coastal residents who want to manage their dunes to be aware that, although their property ownership may extend to the high tide line, management of lands west of what is called the “statutory vegetation line,” or the established upland shore vegetation, whichever is further inland, falls under the authority of the Oregon Department of Parks and Recreation. The statutory vegetation line, which can be viewed online, is often very close to residences, so that homeowners should check with Parks and Recreation regarding what is allowed before tending to their dunes or making improvements to their backyards.