By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews

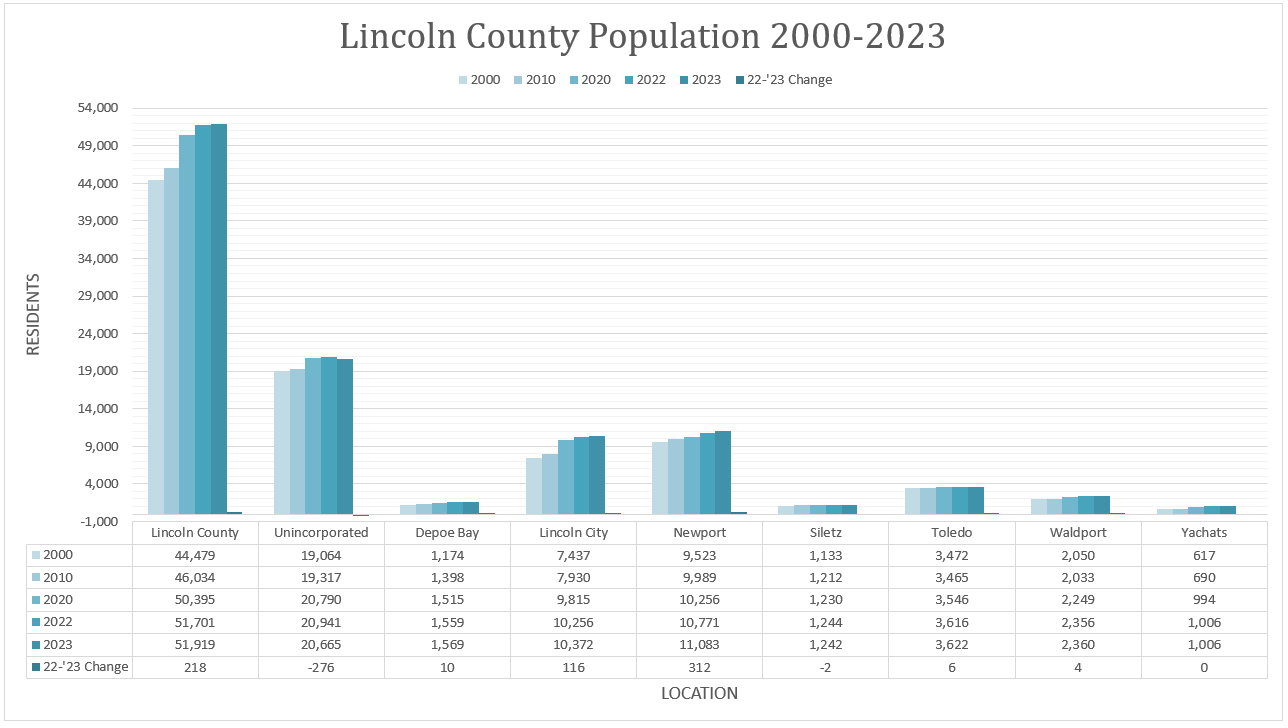

Lincoln County, like 30 of Oregon’s 36 counties, gained population last year, according to new population estimates released this week by Portland State University’s Population Research Center.

The county’s year-over-year gain of just 218 residents, however, continues a pandemic-era trend of little to no population increases for Oregon’s smallest and mostly rural counties, and flashes danger signs for years ahead, according to labor economists.

“The in-migration we used to count on to replenish our work force and our economy has definitely hit the brakes, big time,” said Pat O’Connor, a regional state economist for the Oregon Employment Department. “And, at this rate, it’s very difficult to see how that’s going to turn around.”

Lincoln County was actually on track to lose population this year, according to preliminary numbers released last month. Those figures showed a net loss of 159 residents, putting the county among 10 statewide to dip downward.

The new, revised numbers included refined estimates provided by local governments.

The counties that lost population – Baker, Grant, Harney, Jackson, Josephine and Union – all tend to be smaller, rural areas are not experiencing in-migration.

Other counties to recorded only negligible gains – Gilliam (+19), Sherman (+33), Tillamook (+42), Wheeler (+17) and Wallowa (+1) – also fall into that geographical category.

Labor market challenges

In an economic sense, O’Connor said, that will present significant challenges ahead in those areas’ abilities to attract new workers. The same is also true for rural counties such as Lincoln, Clatsop (+220) and Wasco (+58).

“Unemployment is still near record lows in all of Oregon’s 36 counties,” he said. “It’s awfully tough to see how the work force will be able to grow in light of a tight labor market that will be here for some time to come.”

For counties experiencing either net population losses or negligible gains, the reality isn’t, for the most part, that residents are moving out in search of other places to live, O’Connor said.

Instead, these areas are facing what demographers refer to as “natural decline,” where aging existing populations are simply dying off faster than new births are replacing them.

“For years, obviously before the pandemic, Oregon was a popular place to move to and we were used to experiencing a ‘natural increase’ in population,” O’Connor said. “The pandemic was the first time we started seeing deaths exceeding births, which makes perfect sense since a disproportionate number of older people died in the pandemic.”

Cities drive population

If smaller, more rural areas of Oregon are declining in population, the state’s metropolitan regions are moving in just the opposite direction, according to the new PSU certified estimates.

Washington County led with way with a net increase of 5,693 residents in the July-to-July tally. Deschutes County, powered by population growth in and around Bend, was next with a gain 3,624. Next in order of growth were Clackamas County (+2,514), Lane (+2,080) and Multnomah (+1,728).

O’Connor wasn’t surprised by any of those figures.

“It’s really to be expected that we’re seeing more concentrations of growth in the state’s metro areas,” he said. “”Housing costs still present the same type of challenges we see in rural areas, but Oregon’s larger cities just have more jobs to offer and labor commuting is much, much easier.”

The state as a whole grew from 4,277,533 residents in the 2022 certified estimates to 4,300,931 from 2023. That amounted to 23,397 more residents than last year for a net gain of 0.55 percent.

Data-driven forecasts

PSU’s population estimates are mandated by the Oregon Legislature and intended to help implement policies tied to population size or housing growth.

According to the PSU center, “these data are used within Oregon’s state and local government to ensure equitable distribution of tax revenue, better land use planning, determine appropriation of various state and federal program funds, and for other public policy priorities including education, public health, and redistricting.”

“It’s always important to know where your population trends are going,” O’Connor said. “It gives us an idea of where population and job growth is moving both the fastest and the slowest.”

Looking ahead, O’Connor said he sees more statewide challenges in terms of attracting new residents to the state simply due to its current spate of aging Baby Boomers.

“Currently, 25 percent of the state’s work force is age 55 and above,” he said. “At some point over the next decade, as more workers retired, we’ll expect overall workforce participation to drop like a stone.”

He added, “In terms of worker shortage, there are always up and downs associated with business cycles. But sheer demographics are very tough to battle. And that’s really what we see stretching out ahead.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com

Interesting article, but I’m not sure of a couple of points. First, who qualifies as a new resident? If someone builds a second/vacation home or a vacation rental business house, are the owners counted? It seems every time I drive between Newport and Yachats, I see a new huge home being built along the beach and new roads being cut on the east side of the highway, with more big homes being built on the hills. I’ve lost track of the tear-downs of modest homes so that their land can be used for new monster houses. This has to be contributing to the sky-high housing costs in LC. It shouldn’t be a mystery why younger people aren’t able to make Lincoln County their permanent home, even if they sincerely wish to.

Denise:

Owners of second homes or vacation homes are not counted unless they change the place of their legal residence.

I think we must stop being fatalistic about the housing and workforce crises. O’Connor says: “But sheer demographics are very tough to battle.” To a great extent those demographics are an artificial construct which have become a pernicious feedback loop. Perhaps the solution starts with reducing the tax deductions on second homes and vacation rental businesses and using the taxes to help people own first homes. Simpler said than done, I know, but we could try.