By GARRET JAROS/YachatsNews

The morning sun casts orange peels across a blue-green sea as the Das Bug pulls alongside a buoy floating high above a commercial crab pot buried in the sand below.

Finding the random pots lost at sea during the commercial crabbing season is akin to looking for a needle in a haystack.

Andrew Eastwick snags the pot’s line and spools it around a hydraulic block. The block swings out from the boat as it pulls the line taught. But the line snaps without warning and the 400-pound block comes back toward the boat.

Eastwick, aware of the danger, has positioned himself safely to the side. He tosses the buoy and fragment of line onto the deck and the Bug moves off in search of more derelict gear.

Perry Bordeaux’s 40-foot Das Bug is one of 23 commercially licensed vessels that participated in the 2023 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife post-season derelict gear recovery program. Launched 10 years ago, its purpose is to remove lost and abandoned Dungeness crab gear so it will not endanger whales, other marine life or boat traffic along the Oregon coast.

This year’s recovery ran from the end of August to mid-October and pulled 593 pots, lines and buoys from the ocean. The gear-recovery program begins at least 15 days after the close of the commercial Dungeness crab season and has removed an average of 700 derelict pots a year since its inception.

“It has been a successful program,” said Kelly Corbett, ODFW’s commercial crab project manager based in Newport. “A lot of derelict gear is not intentionally left out on the ocean, but it was identified as a problem that was causing concern for entanglement risk, ghost fishing and navigational hazards.”

Derelict gear is lost or moved primarily by currents, kelp or big storms, Corbett said, or sometimes vessels unintentionally pick them up and drop them in another location.

“Coastwide, I would say right around the Columbia River is kind of a hot spot for derelict gear because of the vessel traffic in that area,” Corbett said. “And really good crab grounds. That combination can have strings get mixed up and pots placed in areas they weren’t originally set.”

Fisherman are not paid to remove derelict gear, but they do have an incentive.

The 2013 Legislature exempted crab pots from Oregon’s personal property law if they are recovered in ODFW’s program. This allows the permitted gear retrievers to keep, sell or return the gear to its original owners as they see fit.

Any vessel with a commercial license can request the permit. Forty boat captains requested permits this season but only 23, operating out of seven ports from Astoria to Brookings retrieved gear.

A special tool

A thin veil of fog clings to the shore break beneath a vault of blue sky as the Das Bug hones in on several derelict pots off Twin Rocks near Rockaway Beach.

Bordeaux’s boat is registered out of Newport but he has been operating from Garibaldi as he plies the waters in search of gear as far north as Tillamook Head. By the end of this day, Bordeaux figures he will have cleared 120 miles of coastline.

Das Bug is outfitted with a specially designed crab pot pump that blasts sand from around buried pots, allowing Bordeaux to retrieve gear impossible for others to pull free. There may be just three such pumps on the Oregon coast.

The pump operates by drawing water in through one hose and then blasting it out a second hose and nozzle. Once a buoy line is snared, it is run through the block, which pulls the line straight. Two massive carabiners are then clipped onto the line and the nozzle is lowered to the ocean floor.

“And it will dredge around the pot down to the pot,” Bordeaux said. “And then we lift the pot up through hole we made …”

Most stuck pots tend to be buried in 10 to 20 feet of sand but Bordeaux has seen them as deep as 40 feet.

The water is glassy with a gentle two-foot swell as Bordeaux stops alongside the second pot of the morning. Helping Eastwick on deck is Garibaldi-based boat captain Levi Cherry, who estimates he has 25 stuck pots in the area because he was crabbing in shallow water and when an April storm cartwheeled others more than a mile from where they were set.

The boat tips starboard as the line pulls tight and the nozzle is lowered. Diesel exhaust mixes with salt air as the pump fires. In less than five minutes an estimated six feet of sand is cleared and the pot, which is empty and polished clean from being buried, is brought on board.

The line – like all the lines pulled – are covered in squirming krill, kelp and other “line critters.”

“You have a whole ecosystem going on,” Bordeaux said. “The krill are what the whales eat and the grey whales sometimes rub them off the lines and can get tangled. And the pots are sanded in so it’s like an anchor for the whale. So the more we can clean this up the less we’re going to have gray whales getting entangled.”

Because pot pumps are uncommon, Bordeaux said many operators have no choice but to cut the lines when their pots get buried close to the surf, which leads to quite a few pots with stray lines in gray whale feeding grounds.

Protecting marine life

Ultimately the goal of the program is to remove lines everywhere, including farther offshore where federally endangered humpback whales are more likely to travel while migrating along the Oregon coast.

“Overall, the program is kind of a cooperative effort between ODFW and the fisherman to try to get ahead of what happened in California,” Bordeaux said.

The non-profit Center for Biological Diversity sued the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in 2017 after the number of whale entanglements off the California coast broke records for three straight years.

California’s commercial Dungeness crab season has been delayed or cut short every year since 2017, although not always solely because of entanglement issues. This year’s season was initially delayed until at least

Dec. 1 because of a high number of humpbacks off California’s central coast. The commercial opening has since been delayed until at least Dec. 16 along the entire West Coast due to pre-season testing that showed low meat-yield in some areas.

There have been far fewer entanglements in Oregon, but in August, the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission voted to extend measures to avoid entanglements, which include limiting the number of and depth crab pots can be placed when humpbacks are most likely to be present.

“When the (derelict gear recovery) program first started up entanglement was definitely a concern,” Corbett said. “It’s been identified as a larger concern since then. But our agency has been doing a ton of work to address risk of marine life entanglement.”

Needle in a haystack

Back on the Das Bug, the pace of pot recovery has bogged down as the crew attempts to unravel what they call a “flower” — when multiple lines are tangled and their buoys splay out on the surface like flower petals.

What usually takes minutes turns into an hour-long effort as the crew struggles with the mess so they can get the pump nozzle down to release four stubborn pots. After burrowing down 18 feet in the sand, they decide to come back during a lower tide.

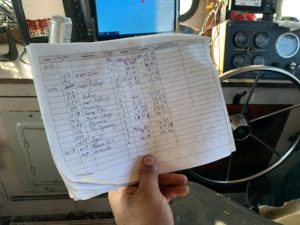

Much of the gear being recovered off Twin Rocks belongs to Cherry, confirmed by his commercial tags attached to the buoys. Information about where each pot is found and which boat it belongs to goes into a log that is verified by ODFW. That information is then posted online by the agency.

“This spot is particularly sticky,” Bordeaux says as he throttles north in search of more pots. “We’ll run uphill a mile to go after others where the bottom is different and they come up easier. We’re not trying to leave any pots out here, but we’re trying to be efficient weather-wise.”

Eastwick glasses the water looking for commercial buoys, which from a distant are sometimes mistaken for birds. There are also recreational pots, which are left alone.

“When we are out here we play the game ‘Bird or Buoy?’ ” Eastwick says.

While ODFW does pass along information on where some pots have been spotted, the trio’s work is mostly like “looking for a needle in a haystack,” Bordeaux says.

A fourth pot is freed before the Bug is engulfed in an afternoon fog accompanied by a plunge in temperature and bucking seas. Fisherman call looking for pots in the fog “crabbing by brail,” Bordeaux says.

Bordeaux maneuvers the boat away from the beach break – it was as shallow as 10 feet — as he turns back toward port. Three more pots are freed along the way, but the plan to go after more south of the jetty is scuttled because of rapidly building seas.

While none of the pots collected contained any dead crab, Bordeaux said he has found everything inside pots from giant agates that have been in the ocean for thousands of years to a whale vertebrae.

“You always wonder if you’re going to pull up a big ole’ gold nugget,” he says.

The real gold however, is in the pots collected. A new 100-pound pot, its lines and buoys can cost $400, said Bordeaux, who estimated he pulled up 125 to 150 pots this fall.

Pots that cannot be tracked to an owner, he will keep for the upcoming season to replenish his own lost gear. One pot can earn anywhere from a $1,000 to $2,000 during the crabbing season. The remainder of the gear will either be returned to the original owner for free — if they are strapped for cash — or returned in trade.

“The old term is ‘brown bottle fee’ – trading favors back and forth,” Bordeaux said. “A lot of us work together, we’re friends and we rely on each other through the season so in most cases we do some sort of an in-kind trade to help each other out, maybe toss $100 on a pot to help cover operating expenses, maybe lend a crewman for a couple of days, or maybe trade for bait.”

- Garret Jaros is YachatsNews’ full-time reporter and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com

Gives new meaning to the phrase “Oregon pot harvest”! Many thanks to these fisherfolk for their efforts, and wishing them all a safe and profitable crab season.

Nice work!

The lay population has no idea how easy for a bouy to be cut and then there is no way to find the pot. The crabpots have a string sewed into a panel that rots and let the crab escape

Great Story. Appreciate the concern for whale safety. Whales play a role in the marine environment that helps generate significant amounts of oxygen into the atmosphere.

What an incredible undertaking. Thanks so much for this important effort!

A very interesting and well written article. Thanks!