By APRIL ERLICH/Oregon Public Broadcasting

Amazon’s plans to install an undersea fiber-optic cable off the Tillamook County coast gained approval from state leaders last week, although with some reluctance.

During a state lands board meeting Wednesday, Gov. Tina Kotek and Treasurer Tobias Read both said they wanted the state to adopt more robust regulations of undersea cables, particularly after a disastrous cable installation by Meta, Facebook’s parent company, in 2020.

That spring, contracted workers with construction companies Edge Cable Holdings and SubCom were drilling into the seafloor off the coast of Tierra del Mar in Tillamook County when the massive drill’s bit broke. Workers weren’t able to retrieve the equipment, so they left about 1,100 feet of 6-inch steel pipe, an 11-inch diameter drill tip, and 6,500 gallons of drilling fluid in the ocean. Two sinkholes later formed along the cable’s pathway.

State regulators didn’t find out about the incident until two months later, when they heard about it from county leaders. At that point they hired environmental consultants to analyze the incident and its aftermath. Researchers concluded the metal equipment now stuck in Oregon’s seafloor will have minimal environmental impacts, although it will likely corrode over time.

Facebook and Edge Holdings executives paid the state $250,000 for damages, and a one-time easement fee of $135,700 — which essentially allows them to leave the abandoned equipment where it is.

During last week’s meeting, Oregon Department of State Lands staff recommended the lands board — which consists of Kotek, Read, and Secretary of State LaVonne Griffin-Valade — approve Amazon’s easement application. The permit would allow the company to operate a subsea cable off Oregon’s coast for the next 20 years.

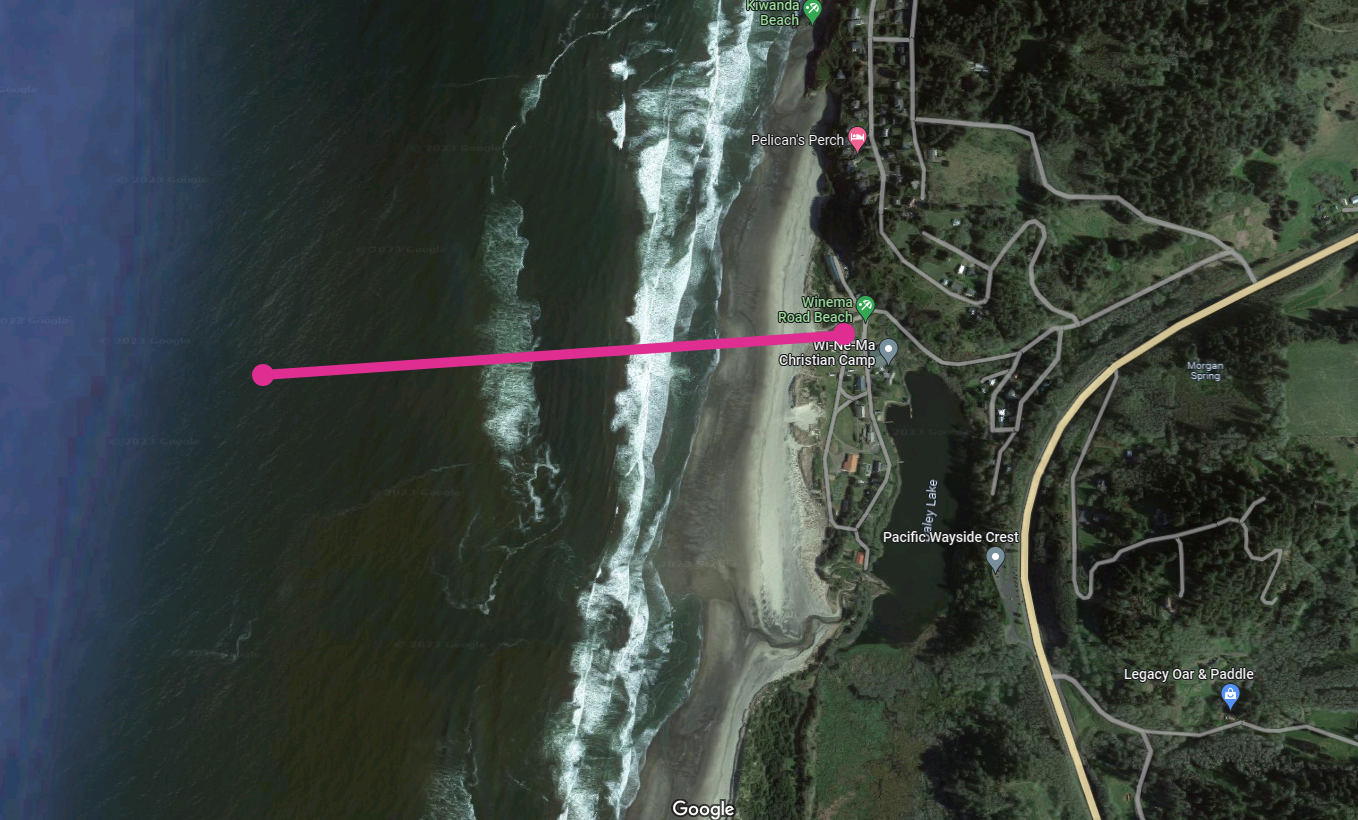

Amazon’s cable will stretch about 9,500 miles from Singapore, across the Pacific Ocean through Guam, to a landing site at the Wi-Ne-Ma Christian Camp in rural Tillamook County. It will also have a branch reaching down to Southern California.

The cable will be buried about 5,000 feet deep along Oregon’s sea shelf to ensure it doesn’t interfere with commercial fishing routes. It will run from the ocean to a manhole at its coastal landing site in Tillamook County, where workers will be able to access it for maintenance. From there, workers will bury it at least 3 feet deep along its route from the coast to Hillsboro.

Trenching work for burying the cable has already begun near Oregon Highway 6, according to Tillamook County officials. Amazon workers plan to finish installing the cable by April 2024.

In its easement application, Amazon said it had considered landing in Washington instead of Oregon, but that state’s outer coast lacks enough fiber infrastructure to connect to other cables in Olympia.

Kotek called the land board vote a “status quo” decision, saying Amazon’s easement mirrored another permit given to Facebook three years ago for a cable stretching from Japan and the Philippines to Oregon and California. Department heads said the company followed existing state rules around subsea cable permits, and that the land board decision was the final step needed to meet Amazon’s construction timeline.

“I will be very frank,” Kotek said at the meeting. “I would prefer to have had this conversation maybe a couple months ago, so we’re not feeling like a little under the gun to make an approval when I think we probably have more we want to discuss.”

After Facebook’s drilling incident, lawmakers passed House Bill 2603. That 2021 legislation requires an advisory council to propose revisions to Oregon’s Territorial Sea Plan, the document that governs how the state utilizes its portion of the seafloor. It hasn’t been updated in more than two decades.

The bill also requires the council to consider a new way of calculating permit fees. Oregon currently charges a flat rate of $5,000 for an easement, with no additional annual fee. By contrast, California charges annual rent for easements. Rent is calculated based on the property’s value, how long the cable is, and a number of other factors.

Oregon’s easement agreements currently include a “future imposition” clause that says if state law changes to require additional fees, the applicant must pay them. Applicants have the option of paying $300,000 to remove the clause from an agreement, which Amazon did. Kotek proposed approving the easement only under the condition that Amazon still be beholden to future legislative changes, but after some discussion, the board ditched that idea.

Members of the terrestrial sea plan work group say creating a new way of charging easement fees goes beyond their jurisdiction, so lawmakers will have to take up the issue. The advisory council plans to provide lawmakers with its recommendations during the 2025 legislative session.

Facebook’s fiber optic cable also runs through Tillamook County, though it built its landing site between residential properties in unincorporated Tierra del Mar. The company didn’t notify residents of its plans, so many were alarmed when they’d heard about the proposed industrial cable landing site near them. Facebook staff declined to comment for this story.

Amazon has taken a different approach. Company officials chose a landing site well away from residential areas. Amazon staff also participated in town halls along with state and local officials, and worked with county leaders to bring cell service and broadband to rural areas that previously lacked them.

“It’s the first time we’ve ever run across a company that’s asking us what they can do for Tillamook County,” said county commissioner David Yamamoto.

Amazon is partnering with Astound Communications to help connect about 270 homes to the high-speed internet provided by the fiber optic cable along its route to Hillsboro, company staff told state leaders last week. The company is also working with Verizon to build cell towers along Highway 6 to bring cell service to the area.

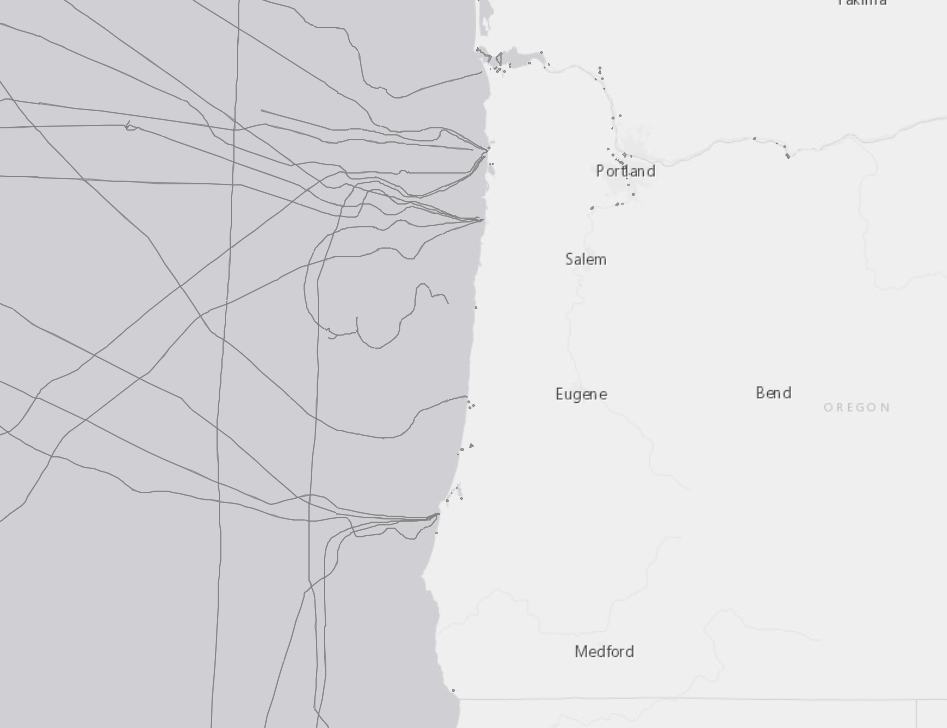

Yamamoto said about seven trans-Pacific cables run through Tillamook County, many running a few feet underground on their way to Hillsboro.

There are about 19 subsea cables off Oregon’s entire coastline, some dating back to the 1990s. Many earlier cables helped people connect by telephone, while newer ones help people connect to the internet and transmit data. Some undersea cables also transmit renewable energy, including Oregon State University’s recently approved PacWave cable.

Oregon will likely see more proposed ocean cables as demands increase for faster data transmission between countries. Companies like Facebook and Amazon benefit from having their own fiber optic infrastructure, because they profit when others want to buy that data transmitting capacity.

Oregon and California have prime landing sites for cables because they host inland data centers. Companies also tend to favor landing in Southern California because that part of the state has fewer regulatory hurdles.

Even so, California overall still has a more robust regulatory structure in place than Oregon.

“California has a very long coastline, much longer than Oregon,” said Cameron La Follette, executive director of the Oregon Coast Alliance. “But it also has very high cable landing fees, and often residents of areas ashore that don’t want a cable landing in the area.”

La Follette said she’s concerned about increased industrial activity in the ocean, since drilling into the seabed can be highly intrusive to sea creatures.

Some state regulators share her concern. During the public comment period for Amazon’s cable permit, staff with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife said the company’s plans for drilling coincide with endangered gray whale migration. State officials feared the whales’ routes would be disrupted by the drilling noise, or that migrating whales could become entangled in equipment.

In a response from 48 North Solutions, an environmental consultant hired by Amazon, workers said they would slow the drilling vessel if whales approach, and they will use specialized muzzles to reduce noise. The consultant also said entanglement was unlikely, since its cable installation process moves slowly.