By GARRET JAROS/YachatsNews

Federal wildlife officials floating the idea of returning sea otters to the Oregon coast in an effort to re-establish their historic range are also hoping they might help combat the devastation sea urchins are reaping on the underwater ecosystem.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service notes there is currently a 900 mile gap in sea otter populations between Santa Cruz, Calif. and the central Washington coast. Otters along the Oregon coast once served as a vital genetic link between those populations, but were mostly driven to extinction by the fur trade of the late 1800s.

Returning sea otters to Oregon would help increase genetic diversity and long-term sustainability of the wild otters by beginning to reconnect the northern sea otter and southern sea otter subspecies.

At the direction of Congress, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service last year completed an assessment of sea otter reintroduction to the Pacific Coast. The 200-page assessment concluded that reintroduction is feasible and would result in substantial benefits to the conservation of the species and to the diversity and resilience of the nearshore marine ecosystem.

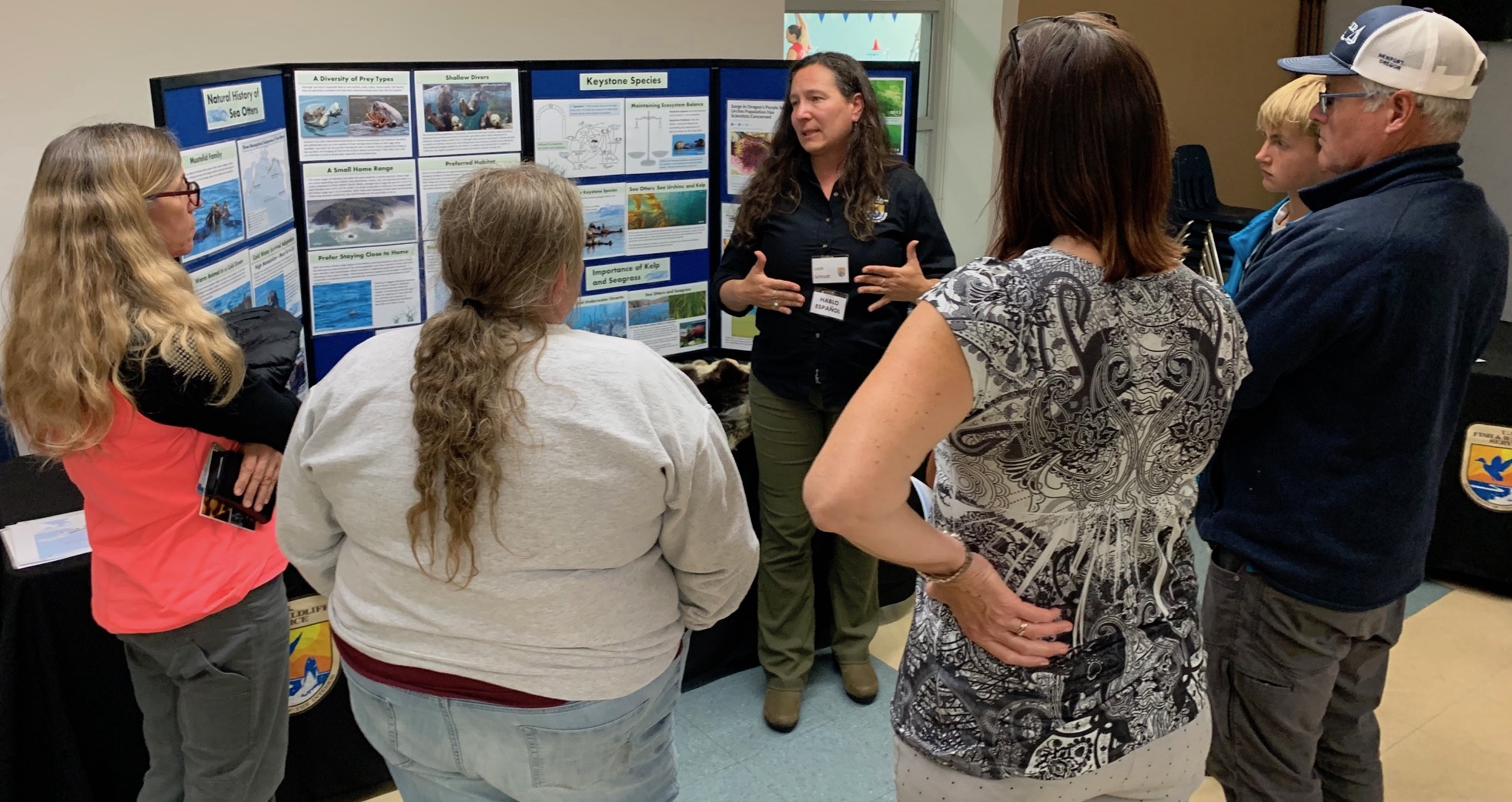

With that in mind, the agency conducted eight open houses in cities along the Oregon coast this week to help educate the public about sea otters as well as get feedback from community members and people who rely on the ocean to earn a living.

A slow trickle of people turned into a full house during the agency’s open house Wednesday evening in Newport, where informational placards accompanied presentations by and conversations with wildlife officials.

“There have been a lot of good conversations and a good turnout,” said Michele Zwartjes, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service field supervisor in Newport, who led the three-person group that wrote the feasibility study. “We’ve had the whole gamut of responses so far, from people who are really excited about bringing sea otters back and who are familiar with some of the climate benefits that come along with sea otters from kelps and seagrass enhancement as a result of sea urchin predation and all of that. And people who just value seeing sea otters in the water.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Zwartjes has also heard from people concerned about how reintroduction could impact their livelihoods — from clam divers in Garibaldi to crab fisherman who experienced the significant impact reintroduction of otters caused to fisheries in southeast Alaska.

Crab industry concerns

Alaska is home to 90 percent of the world’s sea otters.

The 400 sea otters introduced to southeast Alaska in the early 1970’s grew to an estimated 27,000 four decades later, which “decimated what had been a thriving crabbing fishery,” said Tim Novotny, executive director of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission.

The commission does not oppose re-introducing sea otters to the Oregon coast, he said when reached by phone Thursday, but wants to make sure that plans and guardrails are in place to protect the shellfish industry before any reintroduction occurs. The Dungeness crab fishery is Oregon’s most valuable.

“The biggest concern is that we know that sea otters love Dungeness crab and the only history we can point to in modern times of a reintroduction effort was what happened in Alaska,” Novotny said. “And part of the problem is that there was no ability to keep track of the population, and partly because depending on which species they go with, they are a protected mammal. And also, just in general, it’s very hard to manage the cuter of the species so to speak.”

Novotny also points out that sea otters are voracious consumers, eating 25 percent to 30 percent of their weight each day.

The otters are “generalist predators” known to consume 150 different species of invertebrates. They have high energy needs because one of their two key adaptions for staying warm in the water is a high metabolic rate along with their dense fur coat, which contains a million hairs per-square inch, or the equivalent of 10 heads of human hair.

With otters weighing anywhere from 50 pounds for a small female to 80-90 pounds for an adult male, that translates into the consumption of 10-25 pounds of food a day.

But Zwartjes said comparing the release in Alaska, where a large population of otters was introduced to seven different sites in shallow waters with rich habitat, would not be the case if reintroduced in Oregon.

“All of those factors contributed to a very high growth rate, about 22 percent a year for southeast Alaska,” she said. “You compare that to California, which has a very linear coastline without all that complexity, a very narrow continental shelf that doesn’t have a lot of area available to sea otters within their diving depths, and you see a growth rate of 5 percent.”

All indications are that Oregon never had a really large population of sea otters based on the number of skins exported from the area. Also, locations suitable to supporting otters in any number along the coast are very patchy.

“We surmise that (historically) sea otters were not continuously distributed along the coast but most likely in isolated pockets,” Zwartjes said. “The recommendation we’re looking at, if this were to move forward to reintroduce sea otters, would be a very small number of animals to establish a small seed population.”

The hope would be to have enough animals to regain the connectivity between northern and southern sea otters, she added. The numbers the agency has modeled based on a small release would result in 75 to 120 or so otters in 25 to 30 years.

A previous effort to return sea otters to Oregon in the 1970s failed. Of the 93 initially reintroduced, only one was found by 1981. One possible reason for that is that otters have an incredible homing instinct and will travel hundreds of miles to return to their native waters, Zwartjes said. That could be addressed in any future reintroduction by releasing orphaned otters that were raised by surrogate mothers and are not bonded to a particular area.

Novotny feels that U.S. Fish & Wildlife staff along with Siletz-based conservation group Elakha Alliance, which has long advocated the return of sea otters for their cultural significance and other reasons, have been thoughtful in taking into account the concerns of the shellfish industry.

“Elakha did a feasibility study that I thought was pretty reasonable,” he said. “And then the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service I think went even more in depth and when they released their study, I felt it was very thorough, and I felt like they had listened to us and heard our pleas … .”

While there may be no immediate impact to reintroducing the otters, Novotny said it is the long-term effects that are concerning.

“Certain issues have to be addressed beforehand and one of those issues has to be putting certain guardrails in place to protect overgrowth of the species and setting what that overgrowth number would be to protect the fishery,” he said. “And so we’ve said from the beginning, that it’s not a thing that can be rushed. It’s something that should be studied and set in stone ahead of time before you start putting sea otters in the water so that everybody knows what rules are being played by.”

Having those guidelines in place are all the more important because sea otters are protected under several strict federal laws, including the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and in the case of the southern population, the Endangered Species Act.

Potential benefits

Both Novotny and Zwartjes agree on the potential benefit sea otters could provide in protecting nearshore kelp forests and sea grass (both of which provide oxygen, food and habitat to a variety of species including young crab) by eating sea urchins. The urchins began destroying huge swaths of those landscapes after sunflower sea stars, which preyed on the urchins, began dying off in 2014.

One of the people attending the Newport open house was Robert Bailey, president of Elakha Alliance, who has stated in the past that if sea otters were to be reintroduced, it would likely not occur for another five or six years.

“I am very pleased, in fact I am thrilled really, to see U.S. Fish & Wildlife have these open houses, getting this topic out to the public in a way that is digestible, understandable and really is very positive,” Bailey said. “They’ve got to meet the public sooner or later and that they are doing it at this early stage is great.”

It is one thing for an advocacy group to call for reintroduction but quite another for the agency responsible for making it happen to be taking these steps, he added. There is a lot to figure out – when, where, where the animals will come from, what are the costs, do we have enough capacity to do all this stuff?

But Bailey is confident Oregon is on the road to bringing sea otters back to the state.

“So I’m feeling really good about where we are,” he said. “I think this is a positive for everybody. I know there are concerns out there from crabbers, maybe some fisherman, certainly the urchin divers down in Port Orford are nervous, but there’s a lot of goodwill here to make this right.”

- Garret Jaros is YachatsNews’ full-time reporter and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com

If otters are reintroduced then the protection laws much also be changed. Sea otters were reintroduced to Monterey Bay in the 1970s. They have thrived, and the whole ecosystem has changed. One species cannot be allowed to completely monopolize and decimate an area. Take a look at the harbor seals in Alsea Bay.