By GARRET JAROS/YachatsNews

Turning around a life that is well along the path to rock bottom is near impossible. And rising from the ashes of rock bottom – requires the power of transformation.

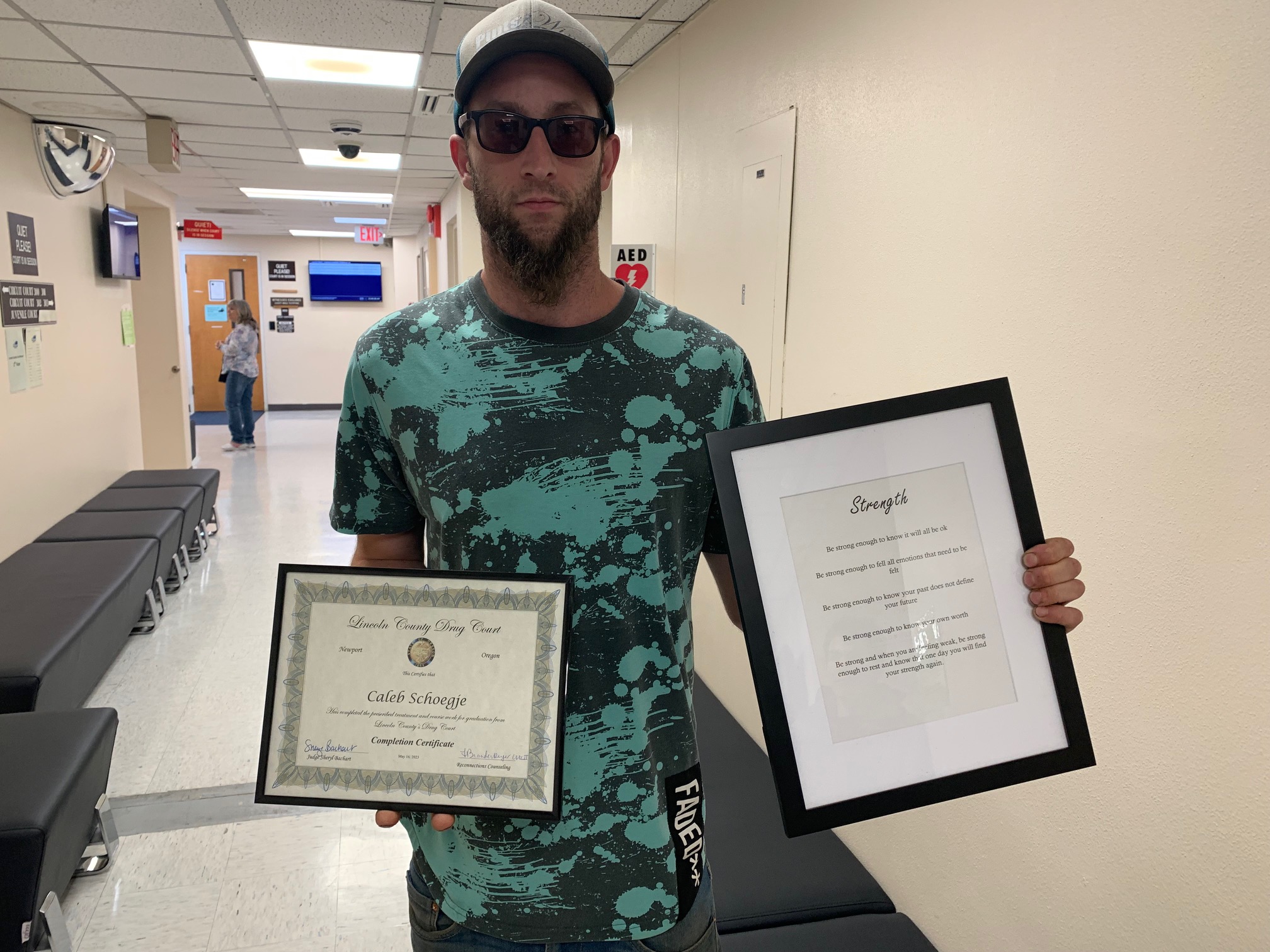

Caleb Schoegje would be languishing in a prison cell today if he hadn’t reached up from the ashes for help – and if help in the form of a specialty court had not been extended to him.

Specialty courts in the United States began in Florida in 1989 with a “drug court” as an alternative to incarceration as a way to help offenders tackle substance abuse and mental health issues.

The first Lincoln County drug court was established in 2006. Today, the county has six specialty courts, which along with the number of participants and graduates, is more than any other county in Oregon with comparable populations — as well as several with greater populations.

Schoegje rose from his usual seat in the back of Courtoom 3 last week and walked to the front, passing the gold-star adorned walls with the names of past graduates before sitting across from Circuit Judge Sheryl Bachart to receive his final sentence.

The 30-year-old Lincoln City resident, who has a rap sheet dating back more than a decade, looked up at the judge and did what all drug court participants do when they sit before Bachart each week. He called out his number.

“Nine-hundred-and-fifty days clean,” he said.

“It’s your last day,” Bachart said. “Congratulations. We are super proud of you Caleb. I know you probably didn’t think this day was going to come.”

“No, I didn’t,” Schoegje said, eliciting laughter from those gathered in the courtroom. “Especially after six months. I was getting ready to go to prison.”

“I know,” Bachart said. “And I think perseverance is a good word. You persevered through it. I know it was challenging for you. You fought the program.”

“Well yeah, I tried,” Schoegje said.

“You did, you fought it,” Bachart said. “But then look where you are at now. It’s fun to see you. You have a smile on your face and it’s just a transformation with you. You should be proud because you worked hard to get where you are. And when you work that hard, it just makes it all the more sweet when you achieve your goals. So congratulations Caleb.”

Specialty courts here

In addition to drug court, Lincoln County offers hope, domestic violence (both established in 2009), mental health and wellness (2020), family support (2022), and aid and assist (2023) courts.

The four main specialty courts – drug, hope, mental health and wellness, and family support — range from 12- to 18-months in duration, although they can run longer if a participant is struggling. There are currently 80 participants in those programs.

The courts are designed to give people in the criminal justice or child welfare system who suffer from substance abuse or mental health disorders an opportunity to achieve sobriety and make positive life changes.

The specialty court programs are optional for certain offenses. But someone who is incarcerated or facing charges must apply via their defense attorney and then be vetted by the district attorney, the court’s program manager, treatment providers, probation officers and a judge.

“We want to determine if they are motivated to really embrace recovery and work the program,” Bachart said. “Because you have some people who are just motivated to get out of jail.”

Lincoln County participants advance through four phases with each phase having base and individual requirements – including the amount of treatment, time in a phase, meetings with probation officers, attending court weekly, and random weekly substance testing.

Phase one focuses on detoxification and changing abusive habits and routines to achieve a baseline of sobriety. Graduation is based on sobriety and all-around lifestyle changes, having a high school diploma or GED, having stable drug-free long-term housing, full employment or enrollment in school or getting on Social Security, and completing a parenting class if the person has children or is a caregiver.

The goal is to provide support and focus on individual needs to promote physical and mental well-being by addressing the root causes of underlying issues with evidence-based treatment. The programs combine treatment, community support, court obligations and supervision to ensure and help people live substance-free.

Costs

There are no easy-to-pluck numbers that give the total cost associated with the county’s specialty courts.

Megan Bostwick-Terry, who manages the specialty courts, points to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals website which claims treatment courts save “considerable” taxpayer dollars, producing $6,208 per participant and returning up to $27 for every dollar invested.

Sixty-five percent of all inmates in the U.S. have a substance abuse disorder, according to the association, and the nation currently spends $80 billion a year on incarceration.

“Treatment courts are the single most successful intervention in our nation’s history for leading people living with substance use and mental health disorders out of the justice system and into lives of recovery and stability,” the website states. “Instead of viewing addiction as a moral failing, they view it as a disease. Instead of punishment, they offer treatment.”

The cost of operating Lincoln County’s four main specialty courts is paid for primarily by a federal grant from the Criminal Justice Commission; followed by funds from the county’s community justice/probation department, which pays for probation officers and the hope court; community partners with in-kind donations for employee involvement; and the circuit court, which pays for judges and staff time.

Program participants pay their own rent at a local halfway-house after their initial stay in a rehabilitation facility somewhere else in the state.

Why so many courts?

One reason Lincoln County has more treatment courts than other Oregon counties is because most are not mandatory, Bostwick-Terry said. It is the presiding judges’ who decide.

“It’s very time consuming,” she said “And having this many specialty courts is not normal. It’s very rare. But they work.”

Three judges oversee Lincoln County’s six courts. Bachart is in charge of four.

She references the passage of Measure 110 by Oregon voters in November 2020, which decriminalized the possession of smaller amounts of certain drugs — including heroin, methamphetamine, PCP, LSD and oxycodone — when asked about the specialty-court program.

“The idea behind the measure and the way it was sold to the voters, was to get people out of the criminal justice system and just engage in treatment,” Bachart said. “Unfortunately, drug use has just exploded because of that, because people in their addiction don’t necessarily recognize that they need the help or have the resources to engage in treatment.

“And there’s no incentive for them to do it if they are not intersecting with the criminal justice system.”

The change affected drug courts across the state because people no longer faced the drug charges that often filled those courts.

Lincoln County made up for the loss by pivoting to accept different types of criminal cases (theft for example) whose underlying motivation was substance abuse. Some of the other counties did not take that tack.

Bachart is proud of the fact that 70 percent of current participants are on “downward departure,” which means if they weren’t in the program, if they are not successful or violate their probation – they would be headed to prison.

“That’s what’s on the line,” she said. “It’s a huge motivation for a lot of them. I think that’s also unique maybe to our county to have so many downward departures.”

One theme that some don’t like to hear, Bachart and Bostwick-Terry say, is that participants uniformly say going to jail helped force them to detoxify and take a break from their situations, helping them get clean and start the work of transforming their lives.

Having a district attorney who is on board is also crucial to the courts’ success, Bachart said, by agreeing to refer people into the programs.

“Our DA believes in it and has been very supportive of these programs and that has been another key to our success,” Bachart said. “We have a lot of cooperation. And I have spent a lot of time investing in relationships with community partners. You don’t do this alone. It takes a huge buy-in and investment from our community partners.”

More than 500 people have taken part or are currently in the program since 2006, and a total of 261 have graduated.

Measuring the program’s success rate is difficult. Some graduates are in prison now while others who relapsed bounced back and now have a decade of sobriety under their belts.

“We plant the seeds,” Bachart said. “It’s a substance-abuse disorder. Some are going to relapse, they’re going to fall down. But what do they do after that? They have the tools.”

The success of the program is typified by someone like Schoegje, who never envisioned himself finishing anything, Bachart said. Yet he completed the intensive program, which is probably the biggest accomplishment in his life.

The reward

Bostwick-Terry has managed the specialty courts for 10 years, longer than any of the judges have been involved in the program.

“I think the greatest reward is when people realize their potential, you see that lightbulb turn on,” she said. “And it’s so heartwarming to see people look out for other people. We hear it a lot. Someone is late for court and five people get out their phones to text them. Just seeing that, how we are a team, all of our participants, is huge and the most rewarding.”

Bachart, who has been a judge for 15 years, has been involved with the specialty courts for four years.

“I tell people it’s the best and worst decision I ever made as a judge,” she said. “It’s the best because it’s so rewarding to see the growth of the people, watch them transform their lives, connect with family that they’ve been estranged from, become the parents I know their kids need.

“It’s the worst decision because you do get to know them, you care about them. You care about their lives. You see them every day, so when they are hurting, when they’re struggling, you take that on, you worry about them. And yeah, it keeps you up at night.”

Schoegjge, who had to endure a lot more praise from the judge and others, along with several gifts before receiving his certificate of completion, offered a few words after.

“I was addicted to meth which led to other things – and you just throw your life away,” he said. “This (program) is hard to get through, it can be pretty challenging with the amount of requirements. I missed a few groups and they got tired of it and gave me two days in jail. If I missed another, they would have given me four days and then six and it just goes up from there.”

His advice to others who are struggling with drug addiction?

“If they offer you a program like this — take it.”

- Garret Jaros is YachatsNews’ full-time reporter and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com

This is the kind of enlightened justice that we need in Oregon. We should extend such an approach to proactive social services for indigent families who otherwise lack resources necessary to change generational trends that manifest in drug use and criminal behavior. We need to stem the tide. Changing lives for the better while saving tax dollars, this is something that transcends party affiliation. Battling homelessness and crime while at the same time diminishing cultural patterns of hopelessness, exploitation, and apathy, these are worthy goals that require high functioning programs. The mentality behind the special courts should be more widely applied in the public sphere.

I’m surprised to see that participants may be required to apply for & be approved for Social Security disability benefits. In the 1990’s, Congress changed Social Security law so that no substance abuser/addict could receive SSDI or SSI benefits unless he/she/they could prove that even they were not using/abusing they had a severe impairment or impaiments, that had lasted or would last ffor at least 12 months (or they’re expected to die in less then 12 months) that prevents that person from performing work at “substantial gainful levels” (usually means 40 hours/week but not always) on a regular & continuing basis.

The person isn’t disabled because he/she/they is doing meth or meth cut w/fentanyl or heroin & won’t get hired for a job and won’t last more then a month or two if they do. There has to be a severe physical or mental impairment/s that would be disabling (by SSA’s rules) even if the person stopped using.

But perhaps the requirement of filing for SS disability benefits is only for what’s referred to as a mental health & wellness court, although the article focuses on the drug court.

For sure there are people who will meet SSA’s criteria, particularly mental impairments, who are substance abusers, but given the difficulty of getting mental health care treatment and particularly mental health treatment that includes seeing a psychologist or psychiatrist at least occasionally, being approved for SS disability benefits for substance abusers is more difficult before Congress changed that rule. Particularly for those under 49.

But . regardless, it’s great that Lincoln county judges have set up these courts, that both the judges and the DA can use the legal/judicial system to work with people with certain problems to avoid jail/prison by getting treatment, a GED, etc., and have more of a chance to move onto a healthier, happier & better off life.