By UO Communications/OSU News Service

Your average sunflower sea star can munch through almost five purple sea urchins in a week, and they don’t seem to be picky about the quality of their food.

That’s good news — and valuable data — for efforts to reintroduce these now-endangered predators to coastal ecosystems along the west coast of North America. It suggests that if sunflower sea stars returned to their former habitats, they could help keep hungry urchin populations in check and possibly help restore kelp forests.

A team co-led by Aaron Galloway at the UO’s Oregon Institute of Marine Biology published the findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society B on Feb. 15. Galloway spearheaded the work alongside Sarah Gravem at Oregon State University. The study is important because kelp, large algae with massive ecological and economic importance around the world, are under siege from environmental change and overgrazing by sea urchins.

“We show, using the experiments and a population model, that these very large-scale purple sea urchin barrens probably couldn’t have developed in the presence of sunflower sea stars,” Galloway said. “Our findings indicate that if Pycnopodia recovers, it should suppress these urchin barrens and help the kelp forest recover.”

Healthy kelp ecosystems are marine biodiversity hot spots. Canopy-forming bull kelp can stretch more than 50 feet up from the ocean floor, creating an underwater forest. Kelp’s undulating ribbony fronds provide valuable habitat and food for mammals, fish and invertebrates.

But times have been tough for kelp forests. Climate change is warming oceans, and that’s stressed the ecosystem from many directions.

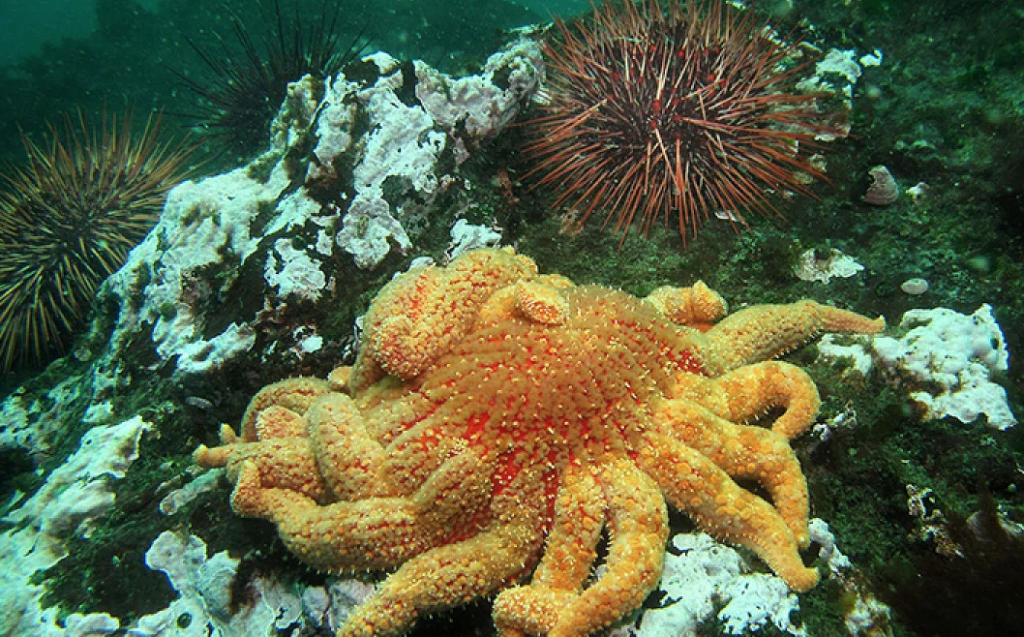

Sunflower sea stars — a meter across fully grown, with up to 24 arms — were once a vital part of such habitats. Alongside sea otters, they helped keep sea urchin populations in check. But sea otters were hunted to near extinction in the 1700s and 1800s and now occupy only a tiny fraction of their former range.

And then, over the past decade, sea star wasting disease — likely triggered by climate change — wiped out almost all the sunflower sea stars in Oregon and Washington. They’re now listed as critically endangered on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List.

“What we saw suggests a clear link between the crash of sea stars, the explosion in sea urchin populations and the decline in kelp,” said Gravem. “It also points to sea star recovery as a potential key tool for kelp forest recovery.”

In warmer waters without many predators, urchin populations have exploded and devoured the kelp. Over time, the habitat has turned into a barren expanse of spiky urchins. Hotter oceans have also stressed kelp directly, making it even harder for the ecosystem to bounce back.

“Once otters were gone, Pycnopodia were still here. So the fact that more than 90 percent of these sea stars died off was huge,” Galloway said. “We’ve had an unfortunate pile of conditions that have been very bad for kelp forests, made worse by recent marine heat waves”

At Friday Harbor Labs in Washington, efforts are already underway to rear baby sea stars in captivity with the hopes of eventually reintroducing them into the wild. But unknowns remain about sunflower sea star biology and the impact they could have if brought back to their former hunting grounds. The Nature Conservancy funded Galloway, Gravem and collaborators at other universities to help answer those questions.

Galloway’s team collected sunflower sea stars at sites in the San Juan Islands, where small populations of sunflower sea stars have managed to avoid the wasting disease. Back in the lab at Friday Harbor, they placed the sea stars in tanks and set up feeding experiments.

In one experiment, they put sea stars in a simple maze downstream of healthy urchins and starved urchins. Then they recorded which prey the sea stars chose to pursue.

Healthy urchins contain far more nutrient-rich material that make them a delicacy in some places. Sea otters, the other major urchin predator, quickly learn to avoid the less nutritious starved urchins often found in urchin barrens. But in lab experiments, the sea stars ate both starved and well-fed urchins.

In another experiment, researchers measured how many urchins a sea star ate per day. The answer — about 0.7, or nearly 5 per week — didn’t depend on whether the urchins were starved or healthy.

It’s an encouraging finding for kelp forest fans.

“If you were to have a sea star dropped into an urchin barren, we have evidence now that suggests they’re going to just start eating their way through it,” Galloway said.

And modeling work led by study co-author Daniel Okamoto of Florida State University hints at just how big this effect could be in the wild. Even accounting for some sea stars getting eaten or not chowing down on as many urchins as they did in the lab, calculations suggest that sunflower sea stars could play a pivotal role in controlling urchin populations and restoring kelp forests.

“Eating less than one urchin per day may not sound like a lot, but we think there used to be over 5 billion sunflower sea stars,” Gravem said. “We used a model to show that the pre-disease densities of sea stars on the U.S. West Coast were usually more than enough to keep sea urchin numbers down and prevent barrens.”

Because sunflower sea star recovery is unlikely to happen in the near term without intervention, Gravem said, researchers have developed a “Roadmap to Species Recovery” that includes the world’s first captive breeding program for the species and a pathway to re-introduction.

With ongoing backing from the Nature Conservancy, Galloway, Gravem and their colleagues will continue to explore the ecological role of sunflower sea stars in future field studies.

“A lot of times as marine ecologists we’re working on projects that are neat to a few scientists,” Galloway said. “But this has a big conservation implication.”