The discovery of a dead orca found tangled in recreational crabbing gear 25 miles off Newport in June is prompting a reminder from state officials that crabbers need to properly mark their equipment under a 2-year-old Oregon law.

The carcass of the approximately 16-foot-long orca was first spotted and photographed June 27 by a fisherman about 25 miles west of Newport dragging recreational crabbing gear. It was the first known case of a killer whale dying in Oregon coastal waters after being tangled in crabbing equipment.

The dead orca was spotted a second time July 7 10 miles off the mouth of the Coquille River. Fishermen recovered the gear and staff from the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife and Oregon State University examined it.

“The gear wasn’t marked with the owner’s identity, so it is not legal gear as per Oregon regulations,” said Caren Braby, who leads ODFW’s marine resources program in Newport. “In fact, the gear is not consistent with regulations in Washington or California either.”

Braby said it is not clear in which state or what coastal area the gear was from.

In an ODFW news release, Braby said the recovered gear had a sport-type crab pot and was relatively clean, suggesting it bad not been in the water long.

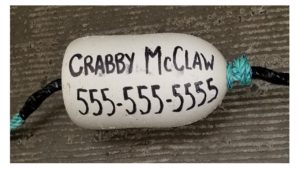

That drew a reminder from the agency that recreational crab pots or rings used in the open ocean water and bays must have surface buoys so the gear can be retrieved. By regulation, the buoys must also be marked with the owners first and last name or business name and at least one of the following: permanent address, phone number, ODFW identification number or vessel identification number. The information must be visible, legible, and permanent.

The regulation does not apply to recreational crabbing from piers, jetties, or the beach where the pot is attached to shore while it is fishing.

Braby said marked surface buoys help managers identify which fisheries and areas along the coast are associated with marine life entanglements. They also help managers develop ways to prevent entanglements in the future, the agency said.

The ODFW said its marine biologists and fishery managers are having good success decreasing whale entanglements in crabbing gear, with the frequency of entanglements dropping the last few years along the West Coast.

The agency has a marine life entanglement web page to explain its efforts. People can also report entangled whales or other marine animals to a federal entanglement reporting hotline 1-877-SOS-WHAL (1-877-767-9425) or the U.S. Coast Guard on VHF CH-16.

Pods of killer whales were spotted up and down the Oregon coast in May and June as they swam close to shore and into coastal rivers, looking to take advantage of harbor seal pupping season.

Although scientists are not certain of the type of orca that died, it is most likely a transient killer whale, by far the most frequent sub-species of killer whales to frequent Oregon’s inner-coastal waters. Transient killer whales feed on other mammals such as harbor seals, harbor porpoises and Steller sea lions, are believed to number more than 400 and are increasing every year.