By ALYSSA LUKPAT/The New York Times and LEE J. SIEGEL/YachatsNews.com

Just after 5:20 a.m. Tuesday, a 4.2 magnitude earthquake struck off about 250 miles off the central Oregon coast. It was nothing groundbreaking, because quakes happen offshore all the time.

An hour and a half later, another tremor rippled through the seafloor.

And then another earthquake struck. And another. And another.

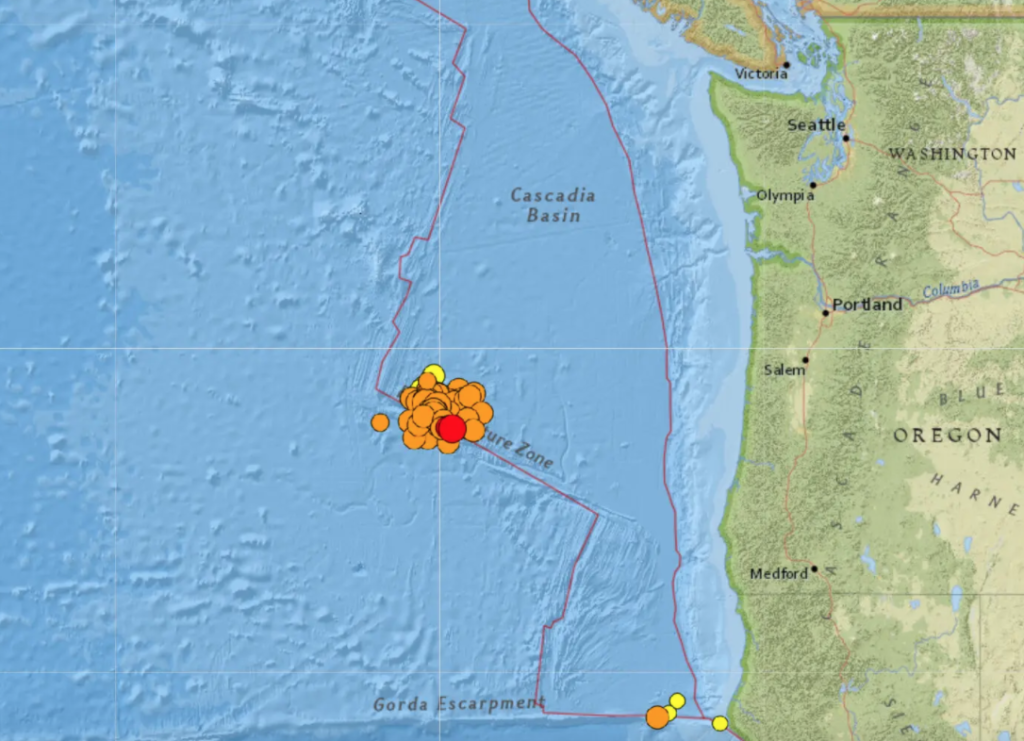

By now, seismologists were really paying attention. Almost 30 earthquakes happened that day along the westernmost segment of the Blanco fracture zone, a roughly 200-mile-long plate boundary off the Oregon coast, according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey. There were two recorded tremors of a magnitude of 5.8, the smallest 3.4.

By Wednesday afternoon, at least 66 quakes had been recorded in the area, according to the USGS. By Thursday night they numbered 96 of magnitude 2.5 or stronger, but the the number of earthquakes seem to be tapering down in frequency.

What has been most impressive about this week’s quakes is the swarm has included 17 tremors reaching a magnitude 5.0 to 5.8 — including two in that range Thursday afternoon. The majority occurred at a relatively shallow depth of six miles. CNN reported that the sheer number of magnitude 5.0 or greater quakes in the region is five times the annual average since 1980, according to a USGS database.

A few coastal residents reported feeling the largest jolts, but the National Weather Service repeatedly announced through the week that the earthquakes were far too small to trigger a tsunami.

The swarm is occurring on the Blanco fracture zone, which is among the most seismically active in North America and part of the boundary of the between the Pacific plate’s eastern edge and the Juan de Fuca plate’s western edge. The Blanco zone is much farther west of the more concerning Cascadia subduction zone and rarely leads to destructive quakes, according to earthquake experts.

The Cascadia subduction zone — where the Juan de Fuca plate’s eastern edges dives beneath the western edge of the North American plate — has produced magnitude 9 megaquakes as recently as 1700.

The largest quakes in the area where the latest swarm occurred were a magnitude 6.2 in 2000 a bit west of the swarm and a 6.3 in 2003 somewhat east of the swarm, said geophysicist Robert Sanders of the USGS’ National Earthquake Information Center in Colorado. Sanders said that in the six years he has worked at the center, he recalls perhaps three or four swarms of magnitude 5 jolts in various sections of the Pacific-Juan de Fuca-North American plate boundaries.

He said the latest swarm could end soon, or go on for days or weeks, and that a similar swarm, but with fewer magnitude 5 quakes, was occurring in the Gulf of California.

Blanco’s swarm not worrying

If 96 earthquakes had struck along a different area, such as the San Andreas fault in California, there could have been chaos and destruction. But this series of small and moderate quakes, known in earthquake parlance as a swarm, was nothing to worry about, said Don Blakeman, also a geophysicist at the National Earthquake Information Center.

“This is just how the earth works in that spot,” he said, adding that the area was “a fairly active zone.”

Someone on the beach 250 miles from the fault might feel the ground shake, he said, but would not need to worry about a tsunami or a powerful quake occurring much closer to them.

The National Weather Service wearily reminded people of that fact on Twitter on Wednesday.

“For the 7th time in the last 16 hours … tsunami not expected with earthquake off the southern Oregon coast,” the agency wrote.

Tsunami is extremely unlikely

In fact, it is extremely unlikely that the Blanco fracture zone would generate a tsunami, said Douglas Toomey, a geophysics professor at the University of Oregon, who has been instrumental in the ShakeAlert warning system implemented in Oregon.

The Blanco fracture zone is what is known as a strike-slip fault, which means its two sides move alongside each other horizontally. Think of when someone “rubs two hands together,” Toomey said. For a tsunami to happen, the seafloor would need to shift up or down.

Other types of faults – like along the Cascadia subduction zone which is close to shore — have vertical movement, which could generate a tsunami.

While a tsunami is an impossible occurrence along the Blanco zone, earthquakes are fairly frequent there.

“If they had an ocean-bottom seismometer out there, it would be recording earthquakes every week,” Toomey said.

He said he was not “entirely surprised” to hear about the swarm but added that the number and size of the tremors were “a bit unusual.”

A 2005 swarm might have eclipsed this one, however, because its most powerful quake reached a magnitude of 6.6, said Susan Hough, a seismologist with the USGS in Pasadena. The two largest tremors from this week’s swarm reached a magnitude of 5.8.

It was not clear what caused this swarm, but Hough said there was a theory that swarms in general could be caused by fluids that “move around” once they get into the earth’s crust.

“We don’t really understand why swarms get started,” she said.

Tissue paper, not cardboard

In an earthquake, stresses that have built up along a fault reach a breaking point, releasing huge amounts of energy. That can set off nearby faults, similar to tipping a row of dominoes.

It is possible, though “exceedingly unlikely,” Hough said, that the swarm from the Blanco fracture zone could set off the Cascadia subduction zone, which is 100 miles farther east.

The Cascadia zone, a fault running from Northern California to Vancouver Island, is like the Blanco zone’s bigger and scarier cousin. It is closer to the coast and much longer, and it would move vertically in an earthquake. A powerful quake there could devastate the Pacific Northwest, seismologists say.

But, again, experts have said that there is no reason to be concerned about the swarm along Blanco fracture zone generating a powerful quake because the earth’s crust is much thinner there than in the area of the San Andreas fault, Hough said.

“It’s like a fault going through a piece of tissue paper,” she explained, “as opposed to cardboard.”

- Lee J. Siegel of Beverly Beach, Ore. is a retired science writer for the University of Utah, Space.com and The Associated Press.