By ALEX BAUMHARDT/The Capital Chronicle

By May 2020, Ethan Kemper had all but given up on school. Banks High School, where he was finishing his freshman year, had gone to a pass/no pass grading system after having in-person school derailed by the coronavirus.

Jacoba Kemper said her son’s classes felt unplanned, communication between the teachers and Ethan lagged and filling out and returning packets dragged on and felt empty for him.

“It was just, for lack of a better word, lame,” she said. Ethan, who has a mild learning disability as a result of brain cancer when he was younger, wasn’t being supported in the ways he needed, she said. “The last two weeks of school he was passing and said he just didn’t want to do it anymore,” she said in a recent interview.

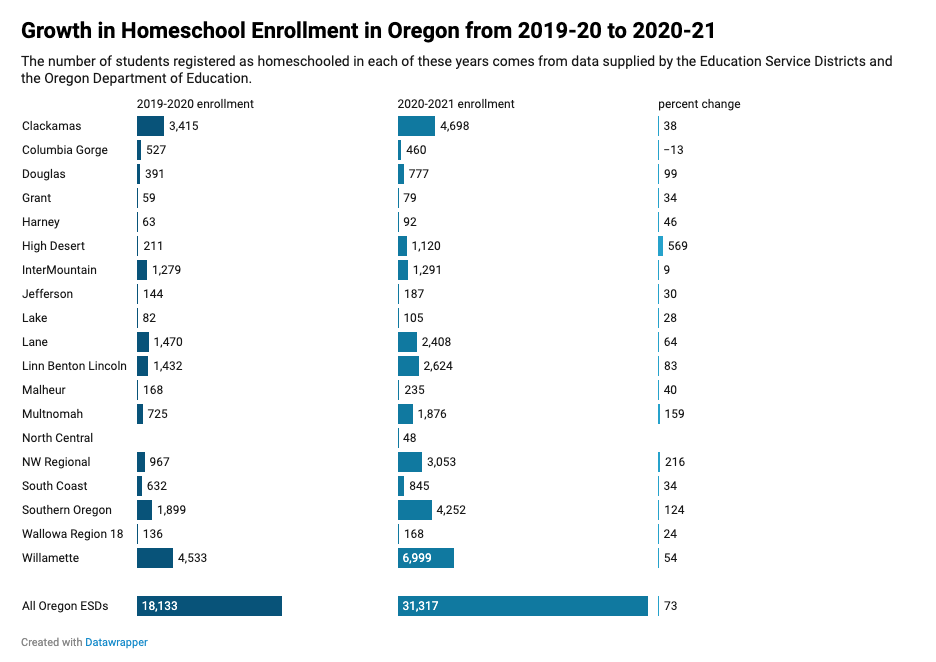

So, Ethan became one of more than 3,000 students in the Northwest Regional Education Service District, encompassing 20 school districts spanning Banks to Beaverton to Tillamook, who chose homeschooling for the 2020-21 school year. Kemper, who had been laid off from her job managing the repair shop at a local tractor dealership, became his pseudo-teacher. Across Oregon, students registered as homeschooled went up 73% from the 2019-20 to 2020-21 school year.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, students registered for homeschooling nationwide doubled between the spring of 2019 and the fall of 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The rise was highest among Black and African American families, whose numbers quintupled.

Stephony Herrera, a Black mother in Corvallis, homeschools her 8-year-old son along with her sister-in-law and her two 8-year-old sons. Herrera elected to homeschool at the beginning of the pandemic, before school districts moved classes online. She is the full-time caregiver for her husband who has a disability that puts him at high risk for severe illness from coronavirus, and she worried about the potential for her son to bring it home from school.

When the Corvallis School District went online and sent home iPads, she felt the remote instruction would leave her son, who has a learning disability, behind and she chose to continue homeschooling.

“He was gonna fall through the cracks,” Herrera said. “It gave me the opportunity to realize some kids aren’t ready to learn some things at the same time, and in the school system you have to fit in the mold.”

She said her son’s teachers told her that he struggled with reading, but she said he’s thriving at home in his reading lessons. She said he was further behind in math than she realized, so she’s paying for online math tutoring to help him catch up.

“I viewed it as an opportunity to know and understand what type of learner my son is. I didn’t realize how much was on the teacher, and how many students those teachers have,” Herrera said.

In 2020, more than 31,000 Oregon students homeschooled compared to 561,000 students enrolled in the state’s public schools.

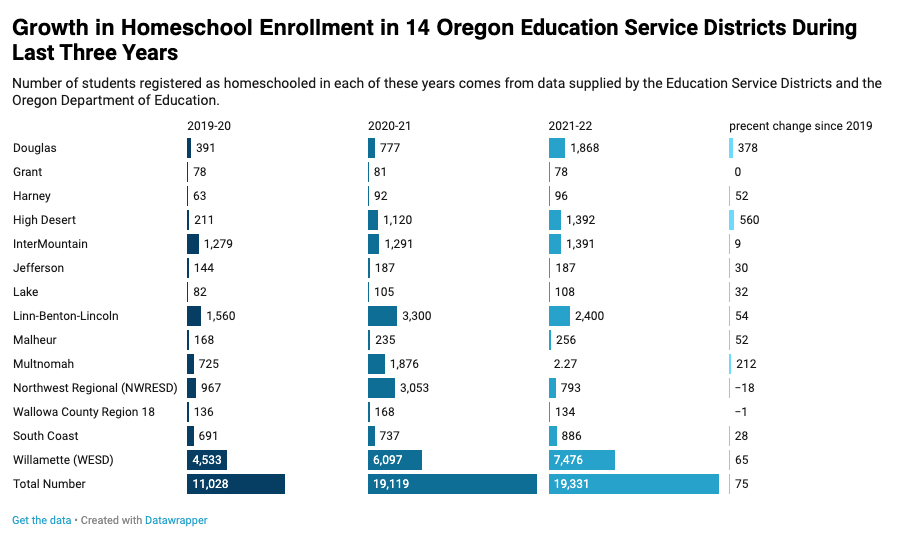

This school year, it appears many of those new homeschoolers have not returned to their districts, according to reports from 14 of the 20 education service districts around the state. Most reported a continuing rise in their number of homeschoolers.

Ethan Kemper’s days as a student changed dramatically when he chose homeschooling.

He went from six or more hours in classrooms each day to spending three to four hours a day on school work. He uses a secular online program called Build Your Library and supplements lessons with books he and his mom pick up from the local library.

“He’s very self-sufficient,” Kemper said. “It’s almost hands off for me.” She said the program is better than what Ethan could get in distance learning from Banks High School and seems just as, if not more, rigorous than in-person school was. “I went to Banks High School,” she said, “They’re still using some of the same textbooks I was using.”

“There are a few parents who have tried homeschooling and distance learning and they’re so frustrated,” she said. “They say, ‘I don’t know how teachers do it, we’re going back to school as soon as possible.’ Other parents are saying, ‘This is the best thing that’s ever happened to us. I’m gonna homeschool forever.’”

– Rosalyn Newhouse, Oregon Homeschool Education Network

—- — —– —–

Homeschooling in Oregon involves little oversight, and parents who undertake it don’t receive any funding from the state. Students are required to take comprehension tests at grades three, five, eight, and 10, and they have the choice to opt in or out of the standardized tests that many traditional students are required to take. The state Education Department on its website recommends content standards and a framework for teaching at home, but parents aren’t required to use it. When it comes to earning a diploma at graduation, it’s up to the local high school to decide whether to award one.

In general, high schools in Oregon don’t confer diplomas to homeschoolers. According to Rosalyn Newhouse, a volunteer with the Oregon Homeschool Education Network, a lot of students who are homeschooled enroll in community colleges during high school to skip the diploma and begin gathering college credit. Newhouse said her group has heard from many parents new to homeschooling this year. The network’s Facebook page has grown by more than 5,000 followers, with another 100 more joining each day.

“There are a few parents who have tried homeschooling and distance learning and they’re so frustrated,” she said. “They say, ‘I don’t know how teachers do it, we’re going back to school as soon as possible.’ Other parents are saying, ‘This is the best thing that’s ever happened to us. I’m gonna homeschool forever.’”

Each school district decides whether to credit homeschool classwork if a student returns, according to the Education Department.

The biggest increase in homeschooling numbers in Oregon since 2019 was in the High Desert Education Service District, encompassing four districts including Sisters and Bend-LaPine. They’ve seen a 700% increase in homeschoolers since 2019.

Paul Andrews, superintendent of High Desert, said the increase was unquestionably due to the coronavirus.

“If we had a trend before, it was that it was going down,” he said. In 2017, the homeschoolers in the four central Oregon school districts he oversees numbered less than 200. Now, it’s over 1,000.

In Oregon, districts don’t tend to ask parents why they’re moving their kids to homeschooling. For most families, leaving school buildings for homeschool is as simple as filling out forms online, but Andrews said many in High Desert’s school districts volunteered that it was because of how the school’s distance learning played out.

“Not sure what the difference would have been linking into a school online as opposed to other online programs,” he said about the growing number of students not coming back this year, many of whom he assumes will be using online curriculums at home.

Other parents told him it was because of mask mandates or the teaching of critical race theory.

“They’re outliers,” he said. School curriculums in High Desert districts related to the role of race and racism in the U.S. haven’t changed in the last year, but what has is the attitude of some parents towards it, Andrews said.

In the Multnomah Educational Service District, Portland Public Schools was the school district with the highest number of students registering to homeschool in the last year, and the increase was greatest for students in grades one through four. Since August, more than 440 more students in the Multnomah Education Service District have registered to homeschool.

The costs to districts losing these students in reductions in state school funding haven’t hit yet but could be more apparent in the 2022-23 school year.

“If these students continue in the homeschool setting for the 2021-22 school year there is the potential for reduced funding for applicable school districts,” according to an email from Mike Wiltfong, director of school finance at the Education Department. He added that other factors in the state’s school funding formula could offset some losses.

When it comes to the money, High Desert school districts could lose when students leave, Andrews said he’s not worried yet.

“Our area overall is growing,” he said. ”But what parents do once this is all over, that’ll be the answer,” he said. “That’s when we’ll be able to see what’s really happened.”

Besides homeschooling, enrollment in charter schools in Oregon – both in person and virtual – went up during the 2020 school year. More than half of the state’s 19 online charters, each affiliated with a school district, hit their enrollment cap of 3% of district students. Overall the state’s charter enrollments went up by more than 7,000 students last year while the state’s overall enrollment in traditional public schools declined by 3%, according to the Education Department.

In Banks, Ethan Kemper will be among those gone from future enrollment counts in his district. Despite feeling Banks High School tried their best under the pandemic, Jacoba Kemper said she now believes homeschooling is better for her son’s education. Next year, Ethan will be a high school senior, and the last classes he takes in his K-12 career will be from home.

“We won’t go back,” Kemper said.

- Oregon Capital Chronicle is a Salem-based news service that focuses on deep and useful reporting on Oregon state government, politics and policy, helping readers understand how those in government are using their power, what’s happening to taxpayer dollars, and how citizens can stake a bigger role in big decisions.