By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews.com

After a decade of near misses and almost collapses, work will finally begin next week just north of Waldport on the country’s first commercial-scale ocean-wave energy project.

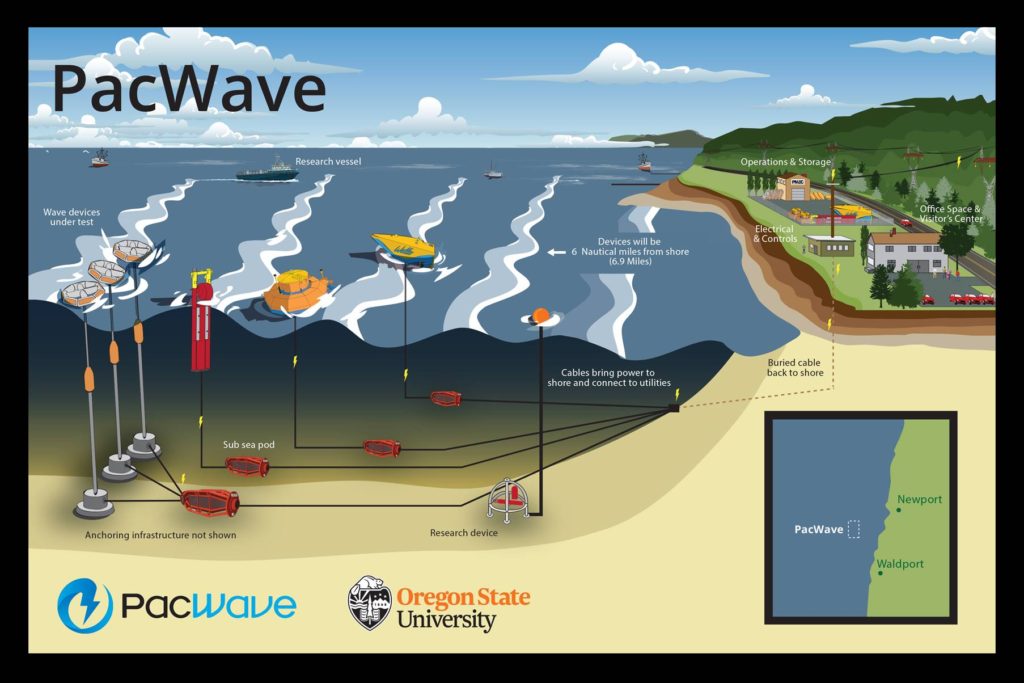

When completed — either in 2022 or 2023 — PacWave South will provide the infrastructure private companies need to test electricity-generating devices and technologies in the open waters of the Pacific Ocean.

And yet, with construction scheduled to start June 1 at Driftwood Beach State Recreation Site, myriad challenges lie ahead that conspire to keep Burke Hales, the chief scientist behind the Oregon State University-led consortium, up at night.

“It’s a bit like Jenga,” he said, referring to the game where a tottering structure is forever in danger of collapsing entirely. “So many really complicated pieces have to line up perfectly to make this all work.”

Project managers face gray whale migration issues. They’ll need to work fast enough this summer to avoid choppy winter waves that would make ocean work impossible. They’ll have to ensure that construction doesn’t endanger nesting areas for the western snowy plover.

And they will have to make sure that the highly specialized contractors needed to bore miles-long underground holes connecting onshore testing facilities to the ocean-based energy devices are available at precisely the moment they are required.

“This is all very delicately poised,” Hales said. “Needless to say, it’s a challenge.”

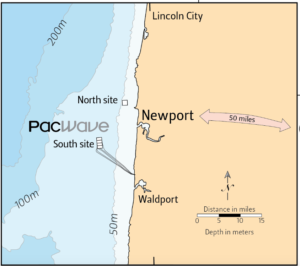

The ocean testing area, located seven miles west of Newport, covers two square nautical miles. It will be connected to a research monitoring center set for construction just north of Seal Rock. Four in-water “berths” will allow up to 20 generating devices to be tested at a time, although project officials don’t expect that number of exceed four at any given time.

Five power and data cables, buried below the seafloor and encased in tubes, will link the devices to the cable-landing site at Driftwood Park, where a second “terrestrial” bore will link the cables to the Seal Rock monitoring facility.

The system will be wired into the Central Lincoln People’s Utility District’s electrical grid and will be capable of powering upwards of 2,000 houses at peak hours, Hales said.

The project’s initial price tag came to $50 million, but that was a full decade ago, when plans were first begin formulated. The cost now is tagged at $82 million, although Hales said it could rise further as construction proceeds. The federal government is covering much of the cost.

The state of Oregon is contributing $5.4 million, with Oregon State University kicking in an additional $3 million. The Murdock Charitable Trust ($740,000) and other private foundations are also on board to help financially.

Allows companies to test devices

But PacWave South’s real benefit, Hales said, is allowing companies to test at least four different types of generating devices over long periods of time to measure productivity and durability in ocean waters.

“We are not a commercial wave-energy site,” said Dan Hellin, PacWave South’s deputy director. “We don’t do the testing, either. We provide the facilities for others to be able to test.”

Prior to the pandemic, the project was receiving quite a bit of attention from European-based wave-research companies, Justin Klure, project manager, said. He expects that to pick back up in coming weeks and months.

“There’s a very strong business case to be made for international companies to come to PacWave and break into the United States market,” he added.

The project’s federal operating license requires that it be completely decommissioned at the end of its licensure, which lasts 25 years.

The Driftwood Beach site will be closed to the public during construction. Once the cables are in and connected, however, the only visual evidence of the project will be two manhole covers leading to and from the ocean test site. A new viewing platform and interpretive display will also be added.

The beach itself will remain open, but the parking area closed for the next 10 months or so, anyone using it will have to walk or bike there.

Not an industrialized coast

In terms of visibility from the shore, PacWave’s Hales said there won’t be much to see. Wave-energy devices don’t poke far out of the water so only a research vessel or tending boat will be about the only evidence the ocean testing unit exists.

Hales also said it’s highly unlikely that commercial wave-energy farms will populate the waters off Oregon. At this point, the cost of producing that energy is far below what the market of such devices could generate, he said.

“We have people saying there will be a city of waves devices off the Oregon coast, producing something that looks like an industrialized coast,” Hales said. “That’s just not realistic.”

For now, the most likely landing spots for devices that test positively in Oregon’s coastal waters are small, remote areas that are sorely lacking in available supplies of electricity, he said.

“Some people estimate that wave energy could eventually produce 10 percent of the global electricity demand,” Hales said. “That’s a reminder that renewable energy solutions are a portfolio. There’s no one horse on which you’ll ride to the end.”

Lincoln County Commissioner Doug Hunt was among those attending a recent online informational session about the project. Like many others, he has followed the PacWave South process for years as it went through the regulatory and permitting process.

“It’s been a long time coming,” Hunt said. “It will be nice to see construction actually starting.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com