By QUINTON SMITH/YachatsNews.com

Once or twice most days the fire engines or ambulance at the Yachats Fire District’s station in downtown Yachats roll out on a call, usually some medical problem, automobile accident or to help an elderly person who has fallen. The firefighters and paramedics — professional or volunteer — are there around the clock and trained to help.

Now, the Yachats Rural Fire Protection District itself may be in need of help.

For the past year it has struggled to control costs of it’s new $8.3 million station being built on the north edge of town. That has stretched the attention of the district’s two administrators and consumed much of the time of its five-member board, which has also struggled with attendance or finding new members to serve. And it has brought into focus issues such as communication and public involvement, the unionization of its firefighters, recruiting staff and volunteers and an upcoming election in May when it will seek renewal of a levy to pay its bills and elect three board members.

The district has a $1.27 million yearly budget, seven full-time firefighter/EMTs/paramedics and two administrators, Frankie Petrick, and administrative assistant Shelby Knife. It has board approval to hire an eighth firefighter to allow it to staff its substation on Yachats River Road — but hasn’t recruited anyone. Petrick says the unionization vote last August is complicating hiring, that the budget has become too tight and it would take months to get a new hire up to speed.

The department has 10 active volunteers, including Petrick as the volunteer fire chief and Knife, but could use at least five more, Petrick says. Like many rural departments nationwide, the Yachats department struggles to find volunteers because of the changes in demographics, jobs and more rigorous training requirements. Back in the heyday of volunteering, the district had 25 volunteer firefighters and a waiting list to join up, Petrick said.

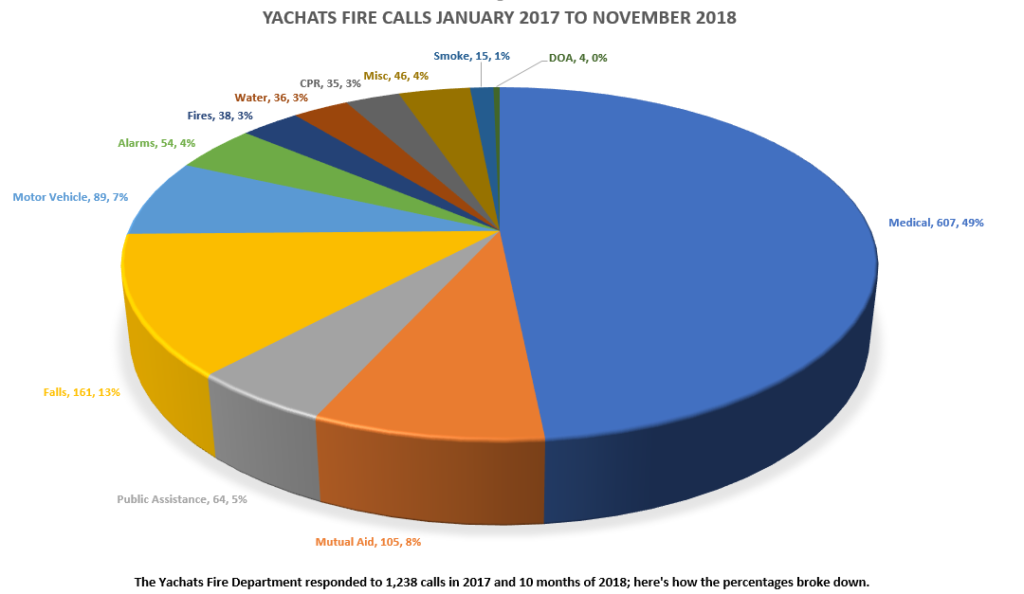

But what the department actually does has also changed over the decades. It rarely puts out fires anymore. The vast majority of its monthly calls — which can range from 40 to 80 depending on the season — are medical calls, falls by the elderly, mutual aid to Waldport and motor vehicle accidents.

Communication with district patrons who live up the Yachats River valley, in Yachats itself and north to the Waldport city limits, comes mostly when it needs voters to approve its operating levies, or in November 2016 when it asked for a $7.7 million bond to build a new fire station. Voters have always said yes.

As a result, the district now takes up the third-largest portion — 16 percent — of all property taxes levied in Yachats.

When the board meets — usually the second Monday and last Thursday of each month — it struggles to have all five members attend, especially in 2018 when it had 19 meetings overall. Director Donalee Pelovsky resigned last May after moving out of the district but had already missed five of seven 2018 meetings. There was one failed attempt to find a replacement; the positions remains vacant. For the remainder of 2018 the board often just had three members at meetings as director Cy Kaufmann missed six of the next 13 meetings. The board couldn’t take action at its Dec. 10 meeting — to, among other things, approve raises for employees and evaluate Petrick — because there wasn’t a quorum.

When it held it’s annual budget committee meeting last June, half of the four public, non-board members didn’t attend.

Three board member positions are up for election in May. They are Position 1 held by Kauffman, a four-tear term; Position 2, held by Katherine Guenther, a four-year term; and, the remaining two years of Pelovsky’s vacant Position 3. The deadline to file with the Lincoln County clerk’s office is March 21.

Board members generally try to recruit people to run, said Ed Hallahan, a longtime board member who has shouldered much of the group’s work on fire station issues. In the past there have been people elected because they had an issue with the district, Hallahan said, but gave up when their issue resolved or they discovered how much they had to learn or how mundane most decisions are.

“We try to identify someone who wants to dig in and work hard,” Hallahan said, adding that it can take 1-2 years before someone really understands how a fire department works. “We have to recruit. No one stands in line to take this job on.”

But it’s hard to know what’s going on — or when the fire board meets — because the only public notice of board meetings is an agenda taped to the door of the downtown Yachats fire station and tacked to the bulletin board in the Post Office, most times two days before the meeting. Board meeting minutes — you have to ask Petrick or Knife to see them — indicate that only three people other than a representative from a city emergency preparedness committee attended one of 19 meetings in all of 2018.

By contrast, the city of Yachats — which has a similarly sized budget and number of employees — often has 20-30 people at twice-monthly City Council meetings and five to 20 people at various monthly committee or commission meetings. It’s actions are scrutinized closely by many residents and it’s website has most city documents, agendas, reports, memos and meeting minutes going back years.

The Yachats fire district has a website (YachatsFire.org) but until YachatsNews.com asked about it in November the last thing on it was posted in July. There is no list of meetings, minutes from previous meetings, budget documents, announcements or safety tips, open burning alerts, hiring or recruiting notices, and rarely updates about its new fire station — the most expensive building project in Yachats’ history.

The Central Coast Fire District in Waldport, which has a similar-sized budget but smaller staff than Yachats, maintains a website (centralcoastfire.net) with all that information on it, including years of budget documents, meeting announcements, agendas and minutes.

In August, the seven career firefighters for the first time voted to unionize, joining the Newport local of the International Association of Fire Fighters, surprising Petrick and the district board. The union and board now have to create and agree to a contract covering everything from pay and benefits to working conditions.

“We’re ready; we’ve been ready for months,” said Petrick. “We’ve had trouble getting them to respond.”

Andy Parker, the president of the Newport local, said there was no single issue that led to the unionization vote but noted that Yachats’ department was the only remaining department in Lincoln County that was not unionized. He said negotiations could begin next month and hinted that there were more issues than just pay and benefits.

Petrick has been the district administrator since the 1990s and the volunteer chief since 2004, has deep roots in the community and an encyclopedic knowledge of the department’s history and operations. She says if people want to know what’s going on or see board minutes they can call, email her or come in to ask about them. She admits being leery of using social media, even websites, and prefers face-to-face communication.

Hallahan says the district could improve its communication. But managing the details of the massive construction project while running the department leaves Petrick and Knife little time for anything else.

“Nothing is worse than a website that is not kept current,” Hallahan said.

Despite all that, the district has had little trouble passing 5-year levies to fund its yearly operations and a bond to build its new station. As a result, the Yachats Fire District alone accounted for 16 percent of Yachats’ residents property tax bills in 2018. Of the 10 other governmental entities levying property taxes in the Yachats area, the fire district’s portion is the third largest behind only the Lincoln County School District and Lincoln County.

The station is being paid for by a $7.7 million bond that voters approved 897 to 591 in November 2016. The bond is for up to 31 years.

In 2018 the bond carried a tax rate – it can vary year-to-year — of 70 cents per $1,000 assessed property value, according to the Lincoln County Assessor’s Office. That means the owner of property assessed at $250,000 paid $187 to help pay for the station.

The fire district has a tax base set in 1997 and two voter-approved 5-year levies that fund its yearly operating budget. In 2018 the total tax rate from those three levies was $1.49 per $1,000, according to the assessor’s office, resulting in a tax bill of $372 on property assessed at $250,000. All total, the owner of property valued at $250,000 paid $559 in 2018 to support the district’s operations and new station.

One of the 5-year levies was overwhelmingly renewed by voters in May 2018. Petrick said the district plans to ask voters to renew the other one this May.