By ELAINE WATKINS/YachatsNews.com

It’s a clear sunny Sunday as Andrea Scharf walks her collie, Rio, up Big Creek Road.

“All those trees would have been cut down if they’d built the resort,” she says, pointing to a stand of hemlock, Douglas fir and spruce. A light mist blows off the ocean, and shafts of sunlight spear through the old-growth forest. A squirrel chitters at Rio from above.

The sound of water is everywhere, from distant waves breaking to the runnels flowing down the mountain.

“Those wetlands,” she points to a field, “how could you keep them intact and keep the creek clean for coho and steelhead? All the buildings would have created runoff and erosion.”

Instead, fields of bright yellow skunk cabbage grow in marshy pools, a sure sign of spring.

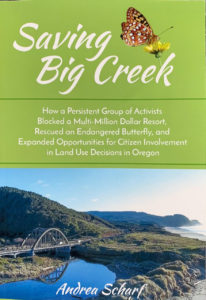

Scharf is walking through the 186-acre Big Creek conservation area halfway between Yachats and Florence. It’s the setting of one of Oregon’s longest-running land use battles and the subject of the Yachats resident’s just-published book, “Saving Big Creek.”

The work chronicles the 35-year fight by coastal residents to thwart a proposed destination resort in a sensitive environmental area. But to research, write and publish the book, Scharf had to show the same perseverance as the resort’s opponents — a group labeled just “a bunch of hippies” by Honolulu developer Victor Renaghan.

For Scharf, the desire to write a book sparked when she attended a 2013 ceremony to celebrate the transfer of one of the last privately owned, undeveloped areas on the central Oregon coast to the Nature Conservancy.

From the time Scharf moved up the Yachats River, she’d heard tales of how the local “hippies” dedicated decades to prevent a destination resort from being built in the Big Creek area. Two of her earliest friends, Jim and Ursula Adler, were part of the Big Creek group. They often spoke of Tom Smith, Paul Engelmeyer, Hans Radtke, Robert Ackerman, and others who persisted until Big Creek was safe from development.

Scharf was intrigued — and worried. Those hippies were now in their late 60s and 70s. Age was taking a toll. Their leader, Tom Smith, was already gone. If someone didn’t step up to preserve the story, it could be lost forever.

She decided this chapter in Oregon’s land-use history deserved its own book.

Oregon’s environmental battles

People have coveted the land around Big Creek for many reasons. In 1969, the Eugene Water & Electric Board considered building a nuclear power plant there. That idea died when the area offshore was determined to be an active earthquake zone.

Environmental battles — clear-cutting of national forests, cities sprawling onto productive farmland, motels wanting to close off beaches, and industries fouling the water and air — were being played out all over Oregon.

It was in this political and environmental climate that the Yachats hippies, led by Smith, reacted when they first saw a sign in 1979 announcing a resort at Big Creek.

Smith arrived in Yachats having worked at Trout Unlimited and the National Wildlife Federation. He understood how the wheels of government turned. First, the group had to find out who owned that land. Then, they needed to learn the law and discover how to make it work for them.

It was a desire to write that lured Scharf to Oregon in 1994, several years after Smith’s death. The legal battles for Big Creek were largely over and had devolved into skirmishes to keep development plans suppressed. Renaghan hadn’t surrendered, even though he’d lost the war.

Armed with a master’s degree in creative writing, Scharf sought a quiet place to spend a year working on her craft. Eventually, life intervened and she moved on to other things, including a three-year stint as marketing director for city of Yachats. But she knew she had the tools and tenacity to write the story of Big Creek.

She began by interviewing the person whose health seemed the most fragile, attorney Robert Ackerman. Ackerman fought alongside Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore. against WPPSS and against the industrial development bonds Renaghan had proposed to fund his Big Creek resort. Scharf showed Ackerman the initial passages she’d written based on their talks. He thought they were terrible.

She widened her circle of interviews. She spent almost four years interviewing people, walking the woods and meadows, reading thousands of pages of planning documents, copying 800 of those pages on her own dime. She came to feel she knew the players as they’d been back then: wild-haired, idealistic, homesteaders fighting to save old growth forests from logging and development.

Scharf spent hours interviewing Renaghan, who, she said, often digressed to rehash grievances over having lost the case and his dream.

Renaghan maintained from the beginning that the resort would prioritize protecting the environment. But Big Creek was a fragile ecosystem and – it was discovered — one of the few remaining habitats for the Oregon silverspot butterfly.

The silverspot laid its eggs under wild blue violets on the meadows just above the ocean. As the eggs hatched into caterpillars, they ate the violet leaves, metamorphized into butterflies, and then flew into the wind-protected forest east of U.S. Highway 101 to mate.

The small creature provided a turning point in the case. It had just been listed as an endangered species. And Smith, a biologist who testified at that hearing, knew this.

Outline of book takes shape

Gradually, the thread of the book emerged as a chronological account. It began with the geology of the area, moved on to its indigenous population, recounted how land use and private property law developed in Oregon, discussed the endangered butterfly and, somewhere about halfway through the manuscript, got to the Yachats hippies.

Scharf showed a proposal and sample chapters to a friend, Carla Perry, owner of Dancing Moon Press. Perry liked the project and suggested sending it to OSU Press. OSU’s acquisition editor also liked the idea and gave it to two reviewers, one of whom was Perry. The second reviewer, however, eviscerated the manuscript.

Scharf still feels the sting.

“There were penciled marks all over the pages,” she said. “He was really harsh, but he was also nitpicky. I remember he nearly wrote off the project because I misspelled the name of the Greyhound Bus Company.”

She pauses. “But as painful as that was, it was the most valuable criticism I got.” The reviewer advised her to restructure the book and resubmit it.

The detailed writing and endless revising weren’t easy, and procrastination was a challenge. Scharf admits her work habits are much like the butterfly’s.

“My style is to flit from task to task. I might write for an hour then go dig in the garden. Write for 30 minutes then make the guestroom bed. Write for 45 minutes then wash the dishes.”

She also needed to read widely in the environmental genre and decided to structure her story like a DNA helix of two parallel plots: one about the people fighting to save Big Creek and the other about the history of the land.

It worked.

“The book is a lot like a mystery novel,” Scharf said. “But instead of being a ‘whodunnit,’ it’s more like a ‘howtheydunnit.’”

Persistence is what strikes Scharf most about the bunch of hippies. Many of them still live around Yachats, up Yachats River Road and near Tenmile. They know what it takes to stick and make a living.

Scharf learned persistence, too. OSU Press’s interest in the book kept her going, but in the end, they passed on the project, calling it “too local.”

She disagrees. She believes the book is a road map of how a group of citizens fought to have their voices heard. In the process, they figured out how to work with county planning commissions, state and federal agencies, courts, the Legislature, and Oregon’s statewide planning goals to protect an irreplaceable stretch of the coast. In doing so they helped change the landscape for citizen involvement in land-use decisions.

Scharf set out to self-publish her book, “Saving Big Creek.” She had it edited several times, kept revising, and eventually knew it was ready.

She established a GoFundMe site and raised close to her goal of $5,000. That paid for Dancing Moon Press to produce 500 copies of the 235-page book.

Nearly half the copies have sold or been given to donors who supported her work, but Scharf still hopes to find a publisher to help market her book to a broader audience.

“It has so much relevance for people today who feel overwhelmed when it comes to effecting change,” she said.

Groups band together to buy property

In 2005, Victor Renaghan approached the U.S. Forest Service about buying his 186 acres. Appraisers established a price of $4.25 million, and the Nature Conservancy got involved. A mad dash ensued to find grants, state parks money, and donations. Then the economy crashed, and the land’s value dropped by half.

Renaghan held firm on price. The Nature Conservancy decided it was a fair price to protect the Big Creek parcel, bought it and turned it over to Oregon State Parks and Recreation to manage.

Kevin Beck, manager of the Carl Washburne State Park area, says saving Big Creek was well worth the fight.

“For the last couple of years, there’s been a lot more private residential development between Yachats and Florence,” he said. “This property is unique. It’s an area without hotels or condominiums.”

Plans include eventually developing trails for hiking and birdwatching and connecting the south side of Big Creek to the Washburne campground. But the primary goal is to continue removing invasive species, such as knotweed, blackberry and gorse.

Sherri Laier is the state park natural resources specialist overseeing the hands-on work at Big Creek. The Nature Conservancy used some techniques to manage the property, including cutting trees, moving slash, and covering invasive species with landscape cloth. But Laier said none were very effective in restoring the habitat to help protect the silverspot butterfly.

Instead, the state uses a wetlands-approved herbicide, leaving a 15-meter buffer between state and federal land to compare active to passive management. Laier feels the state approach is working because now that invasive species are under control, native plants have re-established.

Thousands of densely-planted violets shelter and feed the silverspot eggs and caterpillars. Nectar plants like native thistle, pearly everlasting, and asters bloom in late fall when butterflies are on the move into the forest.

The silverspots had their second-highest recorded numbers last year, Laier said. There have been cougar sightings at Big Creek, and the elk have returned.

“By restoring the wetlands, through mowing and removal of knotweed, the creek’s habitat is improving for salmon and cutthroat trout, too,” said Beck. “It’s a long-term process, but eventually, we’re going to get there.”

An author’s finished work

Walking along Big Creek Road, Scharf arrives at a meadow. Rio is happy to be off-leash and bounds across the field to sniff fresh elk tracks. She searches for knotweed and doesn’t see any.

“Whatever they’re doing out here is working,” she says. “It looks so much better than a few years ago.”

Back at the car, she decides to cross Highway 101 to check out work on the sea meadows. They’re cleanly mowed, but it’s too early to find any violets. Scharf says in her book that she possesses a sixth sense of being able to feel how things were in the past. History is real to her. Right now, so is the future.

“I guess my final thought is that, with a little help from the humans, the Big Creek area will return to something like natural habitat undisturbed by human activity,” Scharf says. “That’s kind of a contradiction but probably the best we can hope for.”

——-

Andrea Scharf’s book Saving Big Creek is available at Mari’s Books and at Toad Hall in Yachats, and on her website: http://www.savingbigcreek.com. The e-book version is available on Amazon, but people need to search for the title, not the author. Scharf is available for speaking engagements and is working on a second book, a fictional memoir.