By KRISTIAN FODEL-VENCIL/Oregon Public Broadcasting

Back in the 1970s, botanist Barbara Wilson found a fun way to pass the time during her daily 80-mile roundtrip commute from Iowa to Nebraska.

“I saw roadkill,” she said. “I would pick up the best of it … and prepare it as specimens for the University of Nebraska at Omaha.”

This wasn’t some odd hobby — she was getting her master’s degree in bird behavior, and she was motivated by science and a desire to protect the environment. Fifty years later, scientists still use her specimens for work like DNA research or to compare past pesticide levels with today’s animals.

But she gave up her roadkill habit when she moved to Corvallis in 1993, to get a doctorate in botany from Oregon State University. Then, a few years ago, she heard about a new nonprofit website called iNaturalist, which was created by students at the University of California Berkeley to crowdsource the collection of scientific data.

“We have these things in our pockets that take pretty good photos. They have GPS antennas, and they’re connected to the internet,” said iNaturalist’s Tony Iwane. “So it’s very easy to snap a photo that has coordinates with it and post it to iNaturalist, and that’s a data point on a map that anyone can use.”

Crowdsourced data has been used to do everything from tracking wolverines in the Cascades to establishing the range of the Himalayan giant honey bee. It’s social media for scientists, but instead of “Hey, look at me in this new outfit,” the offerings are more like, “Hey, look at this cool bug. And does anyone know what it is?”

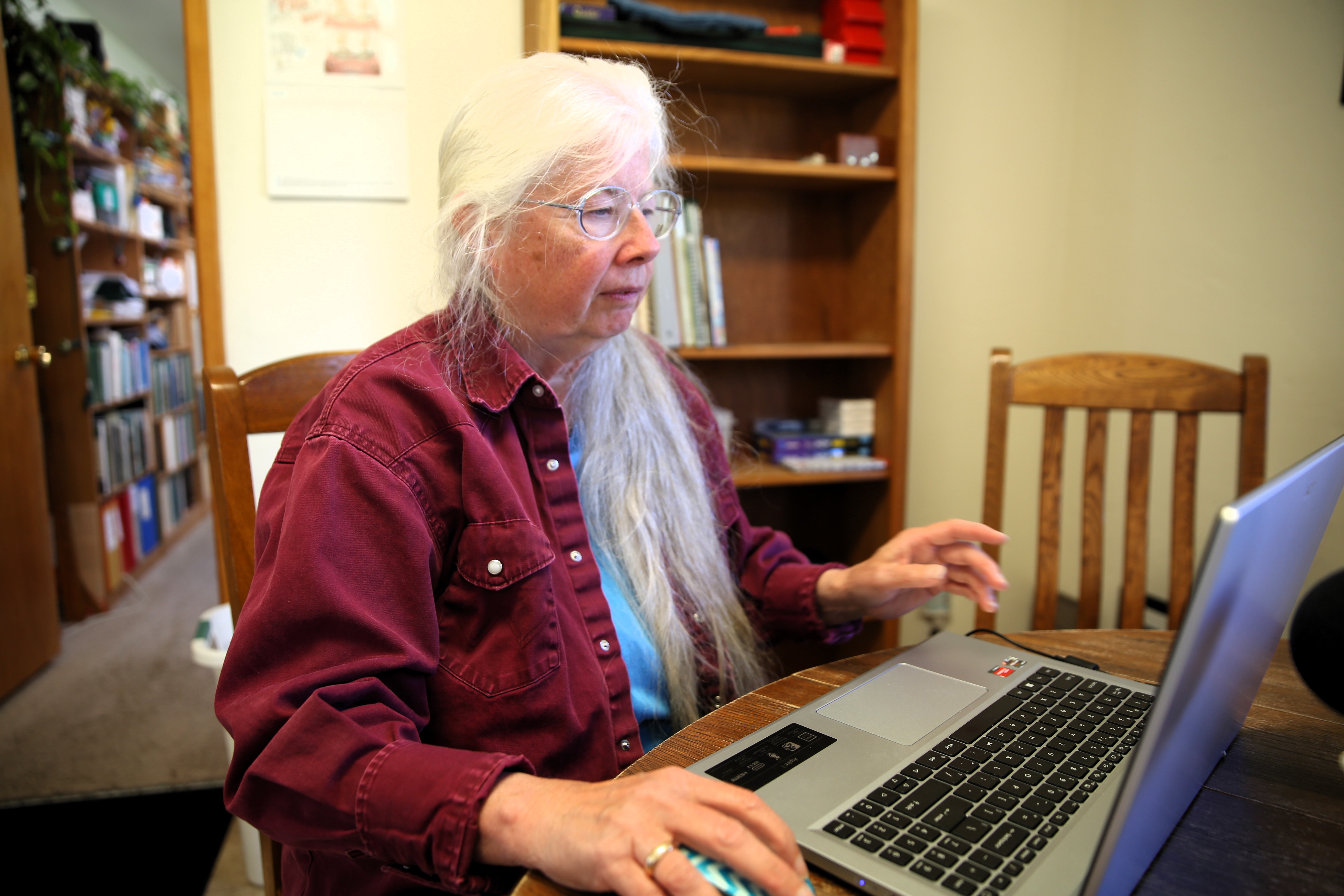

As a botanist, Barbara Wilson documented plants for government agencies and businesses. So it felt natural to upload pictures of plants and animals to the website. She’s made 47,000 observations since 2019.

This summer, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Zoo started asking Oregonians to do their own tracking and upload pictures of roadkill.

“I love collecting things. I love taking pictures of things,” Wilson said. “This gave me an outlet for it.”

So far, she’s uploaded over 160 roadkill pictures for the state.

“I don’t exactly go looking for roadkill. But they’re interesting, and I see things that I do not otherwise see,” she said. “I have never seen a bobcat in the wild, except for one that was flat as a pancake in Wasco County.”

“The state wants to get a better idea about where different animals, different species are getting struck and killed by cars,” said Rachel Wheat, the ODFW wildlife connectivity coordinator.

If Oregon’s naturalists can identify roadkill hotspots, then maybe the state can reduce the number of animals killed in interactions with people each year by removing vegetation that attracts wildlife to a specific area or by building a wildlife crossing.

Washington has 50 dedicated wildlife crossings. California has close to 60. Oregon has just five.

They’re not cheap. An overpass big enough to have trees, rocks and downed logs on it – so elk will cross without getting spooked – can cost $10 million dollars or more. So it’s important to build them in the right place – and hence the need for the Roadkills of Oregon project.

Wheat said Oregon’s first dedicated wildlife crossing was built on Highway 97 outside Bend.

“Since that structure was built, wildlife vehicle collisions were reduced by 80%,” she said.

State scientists counted more than 30 species, large and small, using the crossing. Just how many animals are killed annually on Oregon roads is not clear. But from 2007 to 2013, more than 42,000 wildlife deaths were recorded by the Oregon Department of Transportation.

Before coaxing the family into identifying dead animals on the next road trip, a few warnings. The first is safety. Don’t let the excitement of a fresh carcass blind you to the dangers of wandering the highway with a cell phone camera.

“Make sure that you feel safe when you’re collecting these observations,” said Wheat. “Don’t put yourself at risk to take a photo of an animal. Make sure that there’s a good place to pull off, away from traffic.

“Once you start seeing roadkill, it’s hard to stop seeing them because they really are everywhere,” said Wheat.

There are about 162,000 miles of road across Oregon. Transportation department crews remove large carcasses, like deer and elk. That means the state has some idea about where wildlife collisions are occurring.

“But we really lack information about which other animals are being killed. And we know it’s a significant issue for wildlife,” Wheat said.

The state hopes citizen scientists can document smaller roadkills like snakes, frogs and birds.

“Any individual can take a cell phone camera out and snap a photo of a roadkill event and add it to iNaturalist,” said Wheat. “Then the state has access to that information to be able to learn more about where and when road kills are occurring.”

- This story originally appeared July 24, 2024 on Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Bypasses of roads for wildlife is a great idea–I believe one was built/created along the 2nd “shortening” of western 20, and it has decreased roadkills. But how ODOT, which has announced it may have to lay off a large number of employees, limit state road repairs, is going to find the money for more wildlife bypasses?

While I think ODOT does its best in trying to remove dead deer, it’s not unusual to see a deer carcass near/by the side of 20 for several weeks. Perhaps it’d be easier to increase ODOT’s funding if fewer subsidies/tax breaks were given to large corporations?