By GARRET JAROS/YachatsNews

YACHATS — In a galaxy not so far away a colorful constellation of stars revolves in an unforgiving world of extreme conditions where creatures survive by seemingly unearthly means.

It is a world of toxic poisons and self-created clones, a place of searing heat and numbing cold. And a place not to be missed when exploring the Oregon coast.

“It’s an alien world out there,” tide pool guide Jamie Kish said during a tour this week at Bob Creek. “It is fun for us but can be a nightmare for the animals when the water drains off and they are suddenly exposed to sun and heat.”

Tide pools are diverse ecosystems within rock-walled pools populated by a plethora of plant and animal species — from the base of the food chain to top carnivores. At high tide they are submerged under the ocean. At low tide and in particular at minus tides, they are isolated pools of wonder.

And yes, they are populated by galaxies and constellations.

Kish is one of three tide pool “ambassadors” with the Cape Perpetua Collaborative, which in 2020 began offering free guided tours from May through August. Its mission is to bring together community, science, art and local knowledge to enhance the stewardship of the land and sea in and around Cape Perpetua.

Tours take place only during negative tides. Kish says the best time to get started is about an hour before low tide so as to have enough time. The collaborative hosts roughly 20 tours a month.

Cape Perpetua is the largest of five protected marine reserves on the Oregon coast. It encompasses 15 miles of shoreline and extends three miles out to sea. The other reserves are at Cape Falcon, Cascade Head, Otter Rock and Redfish Rocks.

Kish, who also serves as the tide pool coordinator for the collaborative, grew up exploring tide pools, which led to volunteering at the Oregon Coast Aquarium beginning at age 11. She went on to study aquarium sciences. Her encyclopedic knowledge is only matched by the exuberance and humor she brings to her tours.

Careful where you walk

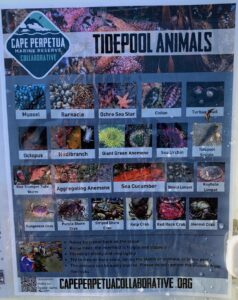

Tour participants may meet at several different locations within the reserve depending on conditions. At Bob Creek, Kish sets up a sandwich board for passersby who can stop to get identification information before continuing on to the pools.

It is there she starts educating tour participants about the reserve – how the area is protected and does not allow for any harvesting of plants or animals except by indigenous peoples who collect, among other things, olive snail shells used for jingle dresses worn at powwows.

She warns about not walking on kelp- and algae-covered rocks to avoid slips and falls, to not walk on fragile mussel beds and to pick your feet up and not scuff when walking across barnacles, which are okay to stand on for a short time before moving on.

“Never touch anything harder than you would an eyelash,” Kish says. “For anemones, do not poke or stick your finger or anything else in their hole. That is their digestive track and it is both their mouth and their butt. A singular hole that does it all. Or as I like to say – one hole to rule them all.”

They can be touched on the outside – which they cover with minute shells to serve as a sunscreen – and on their tentacles.

“They feel sticky to the touch for humans,” Kish says. “Those are actually tiny barbs that give off a poison. They are too small to affect us when we touch them with our hands, but since it has become a thing I should mention, don’t kiss them because it does burn the more sensitive skin on our lips.”

She also passes around what looks like a round bird’s nest but is actually a “whale burp” or seafloor tumbleweed.

“They have nothing to do with whales and usually begin with something manmade like a scrap of wire or rope from a crab pot which things bundle up around,” Kish explains.

Before leading off to the tide pools, she points out the high tide or “wrack line” where glass floats and other treasures including wax balls from a famous shipwreck and even dolphin skulls have been found.

“It is a great place to peruse,” Kish says before leading off with a treasure scoop in hand.

Bob Creek surprises

Bob Creek is well-known for agate hunting, which is allowed because they are naturally occurring and not part of the food chain. The scoops are a rigid length of steel with a handled-grip at one end and a sieved-scoop at the other. They look like golf clubs from a distance and are a sure sign of a veteran agate hunter.

Participants are encouraged to spread out at the pools to get more eyes on more places as Kish makes the rounds to educate. It is not long before the first “Oh wow!” is elicited by the sight of a cluster of colorful ochre sea stars.

“One of my favorite things is bringing people out here and hearing that reaction,” Kish says.

A group of sea stars – whether with five rays (arms) or 20 or more depending on the species – are aptly referred to as a galaxy or constellation.

Despite their numbers being decimated along the Oregon coast beginning in 2014 by the so-called sea star wasting disease, they are making a substantial comeback with ochres doing “phenomenally,” Kish says.

Stars move by taking in water and then pumping it out their arms, which have tiny suction cups they use to pry open the mussels they prey upon.

“When a star has a hunched-look it is feeding on a mussel,” Kish says. “They crack open the mussels and then push their stomachs inside the shell. The stomach then releases a digestive enzyme that turns the inside to soup.”

After consuming the mussel, the star tucks its stomach back into its body. An ochre star consumes about 80 mussels a year.

Taking care where to step between the tide pools can be a challenge as an assortment of small hermit and shore crabs skitter about, wayward sea stars lay in the sand, and dog whelk snails and their eggs and acorn barnacles that resemble prehistoric pods with little dragon-like beaks cling to rocks.

“Numbers are a big thing out here,” Kish says. “Everyone is trying to have as many babies as possible in hopes a couple will live.”

And everything has an amazing story. Once hatched the young snails will eat all of its siblings who have yet to hatch. Acorn barnacles live their lives upside down with their heads cemented to the rock. And those beaks, called cirri, are feathery feet that open underwater to filter food.

Mussels attach themselves to the rocks with byssal threads so strong that scientists are attempting to synthetically create them in labs. Spiny sea urchins bore round holes into the basalt. And many of the animals are “intersex” – meaning they are both male and female – while others can change their gender completely.

And then there are clusters of small aggregating anemones, which may spawn in the summer like everything else, Kish says, “but later in the fall they will split their bodies and create a clone. It takes about two week and is a great adaptation because they can create a security fence with their clones.

“It sounds made up but it happens,” she adds. “It truly is an alien world.”

Tide pools host everything from sea cucumbers to red trumpet tube worms to the occasional wayward octopus stranded by the outgoing tide. Kish points out a Monterey sea lemon, a nudibranch – which means “naked gills.”

“They have their gills outside their body, which is a risk,” she says. “They secrete a citrus-like deterrent to keep predators away. There are so many adaptions like that. It’s not every day we get to see a nudibranch out here — so that’s a big treat.”

When spawning begins tide pools can turn neon-orange or white. Low tides and full moons trigger spawning. And that is typically going to happen at the lowest minus tide of the season, which is usually in early July, Kish said.

“And during minus tides in the winter you can go night tide-pooling and come out with a UV light and everything glows,” Kish says.

Inspire love for sea

Anne Henderson of Tucson is a watercolor painter who finds inspiration in the tide pools.

“I just really love all the different habitat and animals,” Henderson said during Monday’s tour at Bob Creek. “Last year I was at Heceta Head during a super minus tide and we saw well over a dozen species that I’d never heard of before.”

Her friend Paula D’alfonso of Yachats is another tour veteran who praised the tour as well as the ecosystems’ diversity and the fun of “trying to find little critters.”

“And Jamie is just so knowledgeable and a delight to be with,” D’alfonso said. “I’ve been on tours with her before.”

When D’alfonso brings friends along on tours, she said they are always amazed by what they see – “and it’s always changing. Each tour is different.”

The tours try to provide a feel for the habitat so that people can learn to identify what they are seeing and understand what is happening, Kish says. And the hope is it will translate long-term into people voting to keep the reserves protected.

“The more people we have falling in love with the species and the habitats out here the better because it’s only going to create more conservation and more passion,” Kish says. “We hope these tours inspire a love for the area,” she said. “A love that carries forward with future generations to ensure it is protected.”

-

For more information or to sign up for a tour to to the Cape Perpetua Collaborative website

- Garret Jaros is YachatsNews’ full-time reporter and can be reached at GJaros@YachatsNews.com