Lincoln County is getting older and having fewer babies.

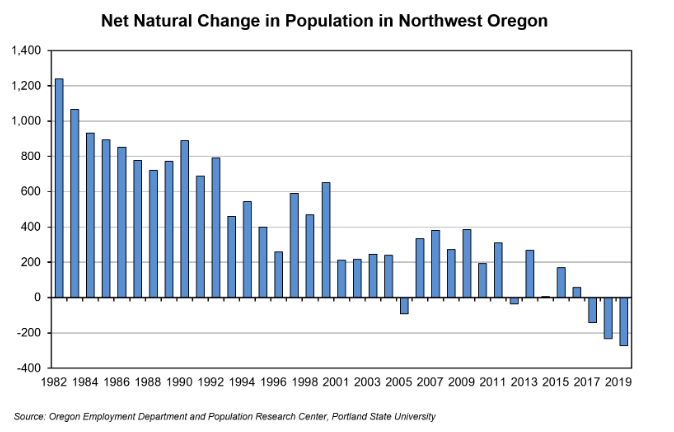

So old in fact, that it accounted for most of the natural population loss – births versus deaths – in the five counties that the Oregon Employment Department lumps together for statistical purposes and calls “Northwest Oregon.” The other four are Tillamook, Clatsop, Columbia and Benton counties.

In a recent analysis and report, OED regional economist Erik Knoder of Newport, said Lincoln County led the five counties with a natural population loss of 251 from July 2018 to June 2019. Lincoln County had 387 births and 638 deaths over those 12 months.

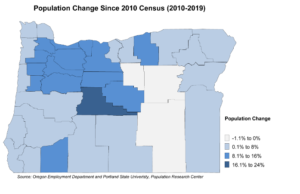

Despite that, the county is still growing slowly because of in-migration of new residents.

About 29 percent of Lincoln County’s population is 65 or older, Knoder said, and has the oldest population of the five counties in Northwest Oregon.

“Natural population loss is traditionally the case for both Lincoln and Tillamook counties, which are notable for their older-aged populations,” he said.

The five counties combined to record 272 more deaths than births during the time period, with Lincoln County accounting for the bulk of the loss.

- Benton County: A net natural increase of 64 people, with 672 births and 608 deaths.

- Columbia County: A net natural decrease of 46 with 460 births and 506 deaths.

- Clatsop County: A net natural decrease of 18, with 372 births and 390 deaths.

- Tillamook County: A net natural decrease of 21, with 248 births and 269 deaths.

“Although the number of births has exceeded the number of deaths for most years, the region seems to be starting a new trend that reverses that,” Knoder said.

Despite the natural population loss, Knoder said, the five-county region is slowly growing due to movement of people into the area, mostly from surrounding counties.

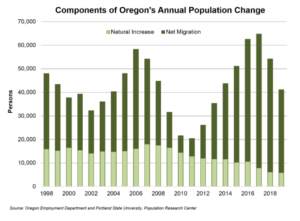

Knoder reported that migration into the area slowed during the Great Recession then picked up again since 2011. In 2006, net migration was about 2,500. By 2010, it was down to 271 people. In 2017 it was 3,022 then 2,652 in 2018.

All five counties had more people moving in than moving out, Knoder said, accounting for the majority of the population growth in the region.

Future population growth within the region will be governed not just by employment opportunities, Knoder said, but also by the quality of life, affordability, commuting times, and a host of other reasons.

Based on estimates and projections provided by the Population Research Center and the Oregon Department of Administrative Services, the five-county region’s population was 259,295 in 2018 and is expected slowly increase by 12,000 over the next five years.

Natural increase slows across Oregon

In 2019, Oregon’s population increased by 41,100 to 4,236,400, according to OED analyst Sarah Cunningham. This marked growth of 1 percent over the year, and growth of 10.6 percent since the 2010 Census.

But of that 41,100 increase in 2019, natural increase contributed just 5,942 to population growth — the lowest since comparable records began in 1960.

The low natural increase is caused by the rise in the number of deaths (36,200), which was the third highest total since 1960. In 2017 and 2018, there were 36,800 and 36,600 deaths in Oregon, respectively.

With 35,200 net migrants, a lot of Oregon’s population increase in 2019 was due to net migration. Over the past 20 years, Oregon had an average net migration of 28,900 people per year. The lowest number of net migrants over the last 20 years was 7,000 in 2010.

In general, we see net migrants increase as the economy expands and more jobs become available. Notice that prior to the Great Recession, net migration was booming in Oregon. As the recession hit, people became less mobile. This, combined with Oregon experiencing a deeper recession than the nation as a whole, brought net migration to its lowest levels since the 1980s. The current economic crisis driven by public health restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic will almost certainly cause migration to fall in 2020.