By CHRISTIAN WIHTOL/YachatsNews

With the pandemic over and Samaritan Pacific Communities Hospital in Newport back to regular operations, the four-year-old facility is proving stunningly popular with record numbers of patients.

That has turned the landmark campus just off U.S. Highway 101 into a strong financial engine — at least for now — for its nonprofit owner, Samaritan Health Services.

At the same time, staff and the hospital’s chief executive officer say the facility — and its smaller sister hospital in Lincoln City — face severe post-pandemic challenges.

The two hospitals — like most statewide — are chronically short of staff. Workers represented by the Oregon Nurses Association and Service Employees International Union say Samaritan must raise wages to attract and keep workers and cover the increasingly steep cost of housing on the central coast.

The two hospitals — like most statewide — are chronically short of staff. Workers represented by the Oregon Nurses Association and Service Employees International Union say Samaritan must raise wages to attract and keep workers and cover the increasingly steep cost of housing on the central coast.

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, Samaritan Pacific’s new, $63 million hospital had been open barely 12 months. Patient volumes dropped as it curtailed many services, including elective surgeries, to hold space open for patients sick with the virus.

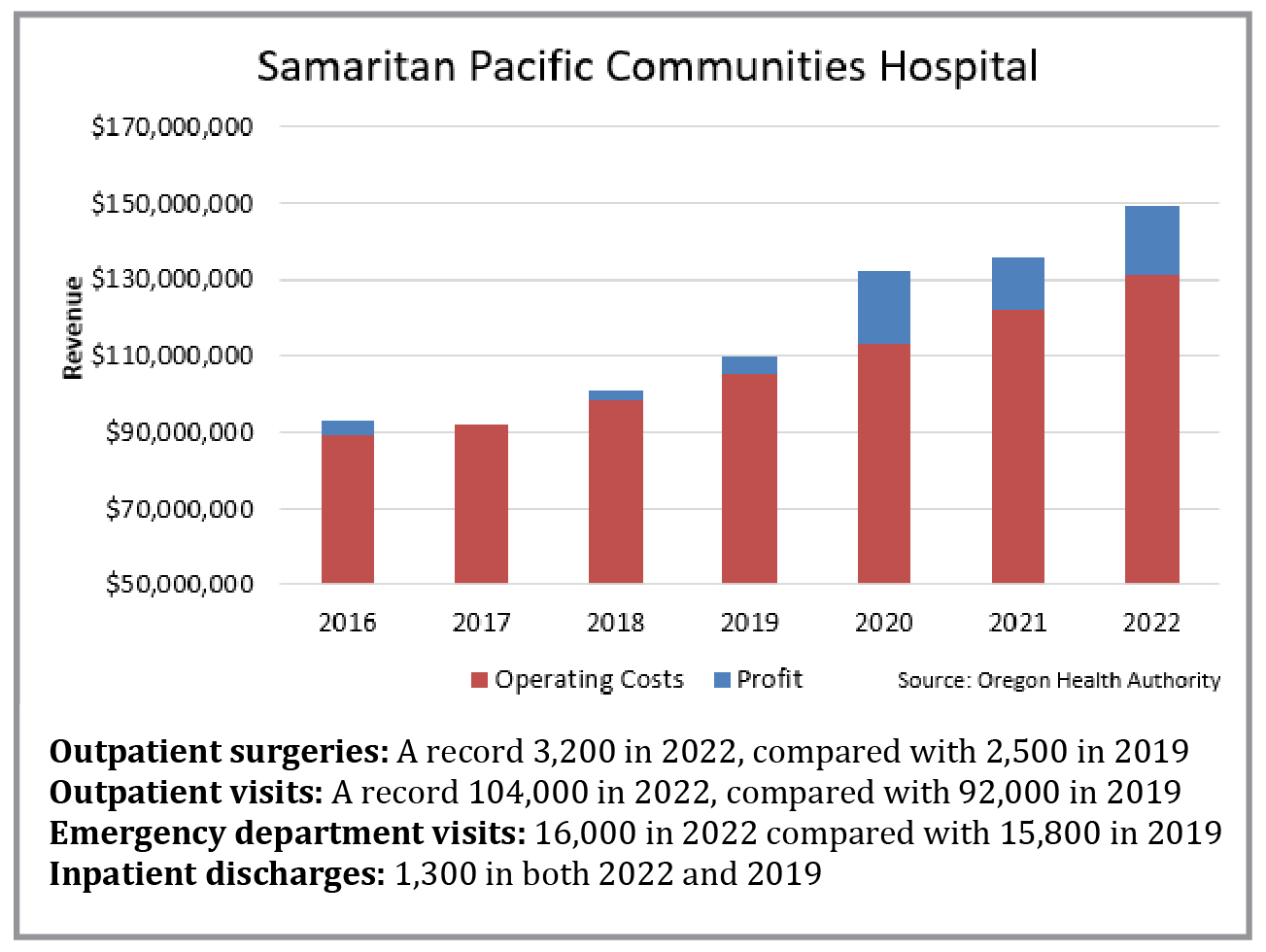

But as state regulators eased restrictions on hospitals, patients are checking into the facility in ever-increasing numbers. The latest numbers, according to Oregon Health Authority data:

- In 2022, total outpatient visits hit a record 104,437, up from the previous year’s 101,374, itself a record. That’s a 25 percent increase in outpatient visits from before the pandemic;

- The hospital’s outpatient surgeries reached 3,171 in 2022, up nearly a third from before the pandemic.

The hospital has just 25 beds, but Samaritan has packed it with niche offerings, from cardiac care to eye surgeries and orthopedics.

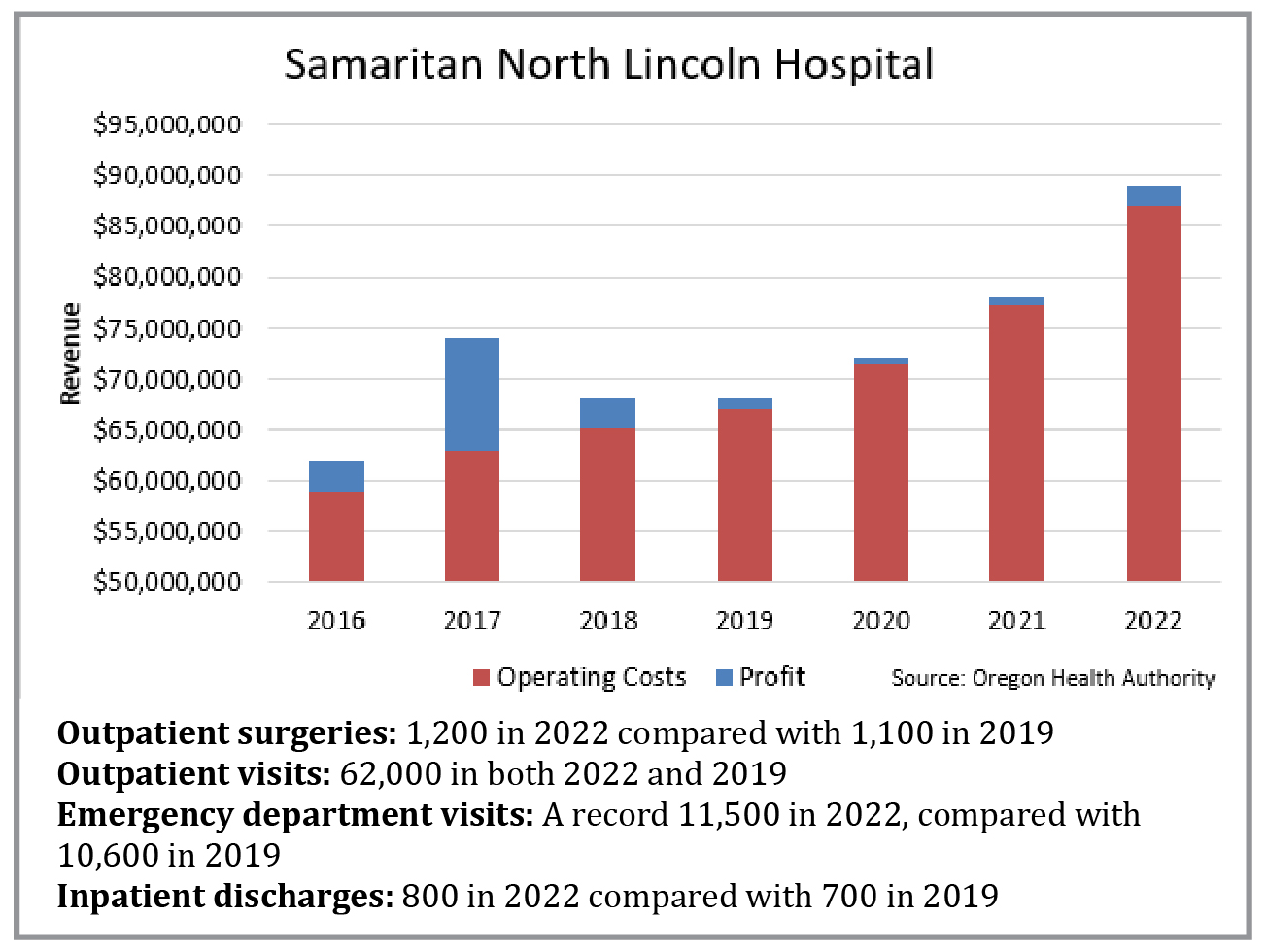

“Our goal is to try to do everything we can so that people don’t have to travel for their basic or in some cases even their expanded care,” said Dr. Lesley Ogden, the chief executive officer of Pacific Communities and the 16-bed Samaritan North Lincoln Hospital in Lincoln City. Samaritan North Lincoln’s facility is also new, opening in 2020 — one year after Newport’s.

The new facilities have been a lure for patients, Ogden said.

“Instead of bypassing our hospitals and going somewhere else for healthcare, we have more people seeking care at our new hospitals,” Ogden said in an interview with YachatsNews.

The boom is not all the hospitals’ doing. The county’s relatively strong economy – with a current jobless rate of 4.3 percent — has helped. A good economy “means people have money to spend on preventive or elective health care,” Ogden said. “And that really keeps our local hospitals healthy.”

Big revenues, profits

The patient numbers at Pacific Communities have boosted the hospital’s bottom line.

Before the pandemic, the 70-year-old Newport hospital typically had annual revenues of about $95 million, and eked out a profit in the 1 percent to 4 percent range – a few million dollars a year.

For 2020, 2021 and 2022, annual revenues averaged $138 million — thanks in part to federal pandemic assistance grants — and annual profits averaged $17 million, or 12 percent.

As part of the five-hospital Corvallis-based Samaritan system, Pacific Communities doesn’t keep those profits. The system’s finances are pooled, with profits from some facilities and services covering money-losing services or going into reserves for capital projects.

Typically, Samaritan wants the Newport and Lincoln City hospitals to produce annual profits of 3 percent to 5 percent, Ogden said.

“Sometimes we get closer to a 1 percent (profit) margin, and sometimes we exceed that and we’re very happy about that,” she said.

Taxpayer-approved bond

The two hospitals are joint ventures by Samaritan and local health districts, the North Lincoln Health District in north Lincoln County and the Pacific Communities Health District that stretches from Depoe Bay to Yachats. Samaritan paid the $42 million cost for the new Lincoln City facility, while property owners in the Pacific Communities district are paying for a voter-approved, $53 million bond that funded construction of the Newport facility. Samaritan spent $10 million on equipment in Newport.

The two Lincoln County hospitals are among 25 rural Oregon hospitals designated by the federal government as “critical access” facilities enabling Samaritan to get full Medicare reimbursement to cover cost of care. The average Medicare reimbursement is about 85 percent of cost, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

The designation aims to improve access to healthcare by keeping essential services in rural communities. Other nearby critical access hospitals are in Florence, Tillamook, Dallas, and Lebanon.

The federal designation also protects communities from over-building by limiting the number of hospital beds in Newport to 25 and Lincoln City to 16. It also requires the hospital’s emergency room to be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Samaritan Health Services stands out as unusual – a relatively small hospital group with two new facilities on the coast and hospitals and clinics in Corvallis, Albany and Lebanon.

Many hospital systems in Oregon and nationwide cut back on new capital spending during the pandemic, as they faced sharp financial losses due to spiraling labor costs spiraled and lagging patient revenues.

Samaritan Health Services also stands out because it managed to scrape through the pandemic with a profit every year: For 2022, a net profit of $20 million on revenues of $1.6 billion; for 2021, a profit of $48 million on revenues of $1.4 billion; and for 2020 a profit of $65 million on revenues of $1.3 billion, Samaritan’s financial reports show.

Pandemic grants from the federal Department of Health and Human Services helped: $6 million to the North Lincoln hospital; $7.5 million to Pacific Communities; and $21 million to the main Corvallis hospital, according to the HHS database.

Employees press for raises

Given the strong finances, some workers feel Samaritan isn’t sharing the wealth. Some say Samaritan isn’t paying enough to keep workers – and they are irked by the large pay increases Samaritan has handed to top executives.

Jessica Maldonado, a registered nurse at Pacific Communities and an Oregon Nurses Association member, said staff shortages, pay that is lower than at many other Oregon hospitals, and high executive compensation are among her main issues.

The three-year contract between the nurses’ union and Samaritan covering 106 nurses at Pacific Communities runs for another year. It provides a total of 9.5 percent in raises over the three years, plus annual step increases of nearly 3 percent for most workers. But rising prices for housing and other costs is eating into that, Maldonado said.

“Right now, our current increases don’t keep up with inflation,” she said. Pay will be a central issue when contract negotiations open next year, she said.

Worker departures have eroded staffing, said Maldonado, who has worked as a registered nurse for two years.

The hospital keeps losing experienced nurses who have 5-10 years on the job, Maldonado said. “I was hired as a new grad and I am looking around and there are less and less of these experienced nurses, where pretty soon I am going to be the experienced nurse with what, two years? I think I’m a good and a competent nurse, but I’ve only been a nurse for two years.”

High executive pay

Samaritan has given some top executives big raises, the system’s filings with the Internal Revenue Service show.

Chief executive officer Douglas Boysen’s pay rose to $1.3 million in 2021, up 33 percent from 2019. The organization’s second-highest paid executive, chief physician executive Robert Turngren, was paid $648,000 in 2021, up 24 percent from two years earlier.

Overall spending on top executives rose briskly. The average of the 29 highest-compensated executives was $462,000 in 2021, up 13 percent from two years earlier. Figures for 2022 are not yet available.

“If you are giving your higher-level employees 10-15 percent annual wage increases, why aren’t your front-line workers seeing similar wage increases?” asked Maldonado.

Meanwhile, SEIU Local 49 and Samaritan are engaged in negotiations for a new contract to replace the three-year agreement that expired earlier this year that covers 135 workers at Pacific Communities.

Pay and benefits are the core issues, said Sheri Khan, a food preparation worker with nine years at the hospital and a member of the negotiating team.

SEIU-represented workers need at least 6.5 percent annual increases to keep up with inflation, and the union is also seeking an across-the-board $18 starting wage for cleaning staff, dietary aides and other similar positions, Khan said. Now, a number of starting wages are under $17 an hour, she said.

The hospital is “a good place to work. We just have to play catchup. We have to stop losing people, and the only way we are going to do that is to increase wages and give good benefits,” she said.

Many vacancies

Ogden says the two hospitals she oversees are doing their best to fill jobs.

Pacific Communities has about 500 workers, and North Lincoln about 400, she said. Together, the two have about 80 vacancies, from registered nurses to lab and imaging technologists and respiratory therapists, she said. The hospital is using costly temporary labor to fill about 30 jobs at the two hospitals, she said.

Ogden said the new facilities were a big boost to patient care when the pandemic hit. Their modern, flexible space could be easily configured to cope with surges of Covid patients, and the modern air exchange systems combated the airborne virus, she said.

“It’s been a blessing to have these types of facilities,” Ogden said.

Now, the new Newport facility, with its surgical suites, is an attraction to some medical professionals, she said. But the shortage and high cost of housing are big hurdles for potential employees, she said, especially for lower-paid workers.

Partial fixes include Samaritan improving its national advertising, and Pacific Communities’ ongoing development of on-the-job training for entry-level spots such as medical assistants, that can be filled by local residents, she said.

“It’s hard to attract people to move to an area for those jobs. It’s much better to develop a workforce here,” Ogden said.

Raising worker pay is also important, Ogden said.

“But when your costs are growing so much, you are like (wondering) where is all this money going to come from?” she said.

So, Ogden said, Samaritan systemwide is also focused on becoming more efficient and on increasing revenues. And it wants to plug gaps in its service offerings, she said.

The latest addition, to be run by Samaritan, is the 16-bed Samaritan Treatment and Recovery Services residential and outpatient facility for patients with substance use disorders. Projected to open in 2024, the campus in Newport is a combined venture of numerous entities. With up to 40 workers, it will likely run at an operating loss, Ogden said, which Samaritan will cover.

Meanwhile, to try to address the scarcity of housing for hospital workers, Pacific Communities rents 20 apartments, including some RV spots, which are used by new employees and contract workers. The hospital may try to secure additional units, she said, but that also poses a dilemma.

“We don’t want to take away from the inventory that’s available for local people,” she said.

The long-term solution is for the community to allow and encourage more housing construction, she said.

Lawsuit with contractor

And there’s another unresolved problem: Alleged construction defects at the Newport hospital. Samaritan and its general contractor remain snarled in a legal dispute in Lincoln County Circuit Court over purported deficiencies in the building’s flooring.

In a lawsuit it filed in late 2021, Samaritan is seeking $12.7 million to repair defective flooring, “property damage and life-safety issues,” and a further $13.4 million for “loss of use of the hospital,” according to the complaint against The Neenan Co., a Colorado contractor.

Problems with flooring in some parts of the hospital include “bubbling, flooring separation, curling, material pulling away from the walls and doors, buckling, and cracking,” the lawsuit said.

Neenan’s repair efforts, which lasted for 18 months after the hospital opened, failed to fix the defects, the lawsuit said. “Samaritan notified Neenan that the problems with the flooring also created health and tripping hazards for patients, visitors, and Samaritan personnel,” the complaint said.

Neenan responded that all problems were “solely or substantially caused by Samaritan’s own negligence or fault, including but not limited to faulty design directions, improper product specifications, and misuse of the installed flooring in violation of applicable standards including manufacturer’s recommendations.”

If the flooring wasn’t properly installed, that may be the fault of subcontractors, Neenan said.

- Christian Wihtol is a Eugene-based freelance journalist specializing in health care. He can be reached at wihtol@Yahoo.com