By JULIA SHUMWAY/Oregon Capital Chronicle

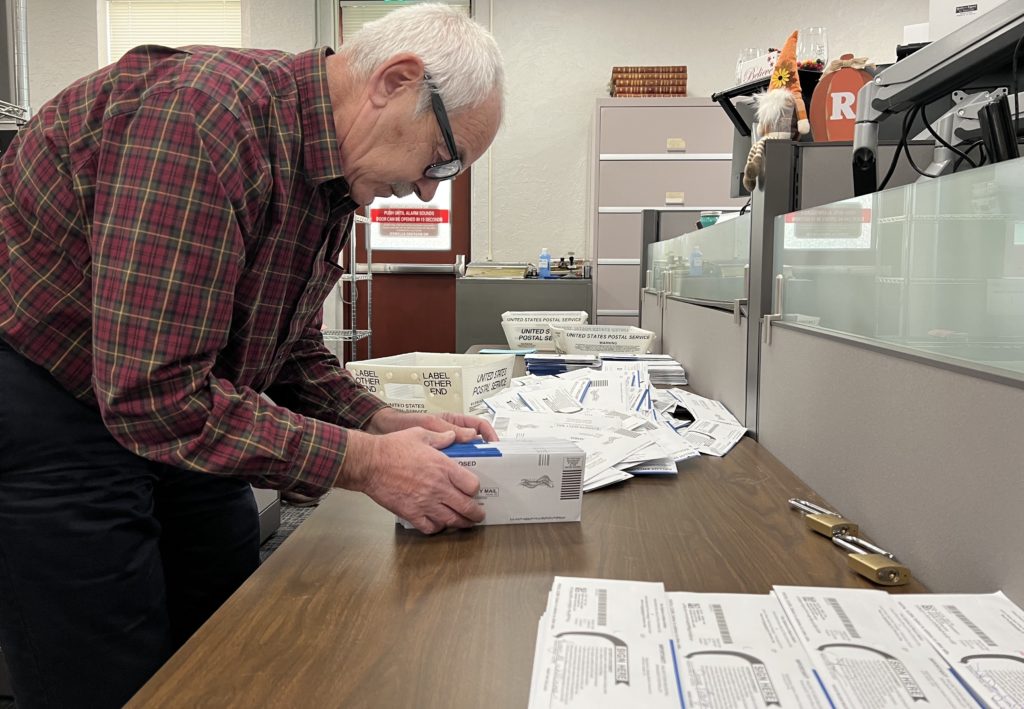

SALEM — Local election offices throughout Oregon are understaffed and underfunded headed into the 2024 presidential election cycle, according to a “grim” report presented to state lawmakers Tuesday.

The report from Reed College’s Elections & Voting Information Center was based on months of interviews with county clerks and other elections staff from 34 of Oregon’s 36 counties, who oversee elections with as few as 1,000 voters or as many as half a million.

Secretary of State LaVonne Griffin-Valade told members of the House Rules Committee that the report backed up the hundreds of anecdotes from local officials in Oregon and nationwide about increased stress on election offices. In Oregon alone, top election officials in 12 counties have left their jobs in the last few years, many citing fallout from the 2020 election and threats and harassment from a vocal minority who denied election results.

“This report is a grim look at what our county clerks face,” Griffin-Valade said. “It is also a testament to their professionalism and ingenuity.”

The Oregon-centric report follows a series of national surveys the center conducted in partnership with the Democracy Fund, a nonpartisan foundation in Washington, D.C. The November 2022 survey found that one in four local election officials, and two-thirds of those in large cities, faced violent threats after the 2020 election.

“The cloud over all of this is the political environment to some degree or the perceptions,” said Paul Manson, a Portland State University political science professor and the center’s research director. “(In) one out of five of our interviews, we had to pause because it was just too emotional.”

One of the clerks interviewed no longer feels comfortable telling strangers what their job is because they’re scared of the reaction, Manson said. Concerns about threats and harassment also make it harder to recruit employees.

Job postings, description and compensation don’t match the current job requirements for county election workers, Manson said. They’re usually classified as clerical jobs, but election workers now have to do more outreach and public engagement, spending time debunking misinformation and talking to adversarial voters. One Oregon official interviewed for the study noted they would make more working at the In-N-Out Burger across the street than in the elections office.

Those increased needs come as counties, which bear the brunt of election costs, face tight budgets. In most counties, clerks split their time between running elections and recording documents such as deeds and mortgages.

Many counties rely on fees from recording documents to pay for elections. When higher mortgage interest rates drove home sales down, counties made less money. Most election offices in small or medium-sized counties have staffing at or below their levels from five to 10 years ago, despite Oregon having nearly 800,000 more voters now than it did in 2013.

Even Multnomah County, which has the largest election division in the state, lags similarly situated counties in other states. Multnomah County has 12 full-time election workers, half as many as Denver County in Colorado though it has about 30,000 more registered voters than Denver County. Like Oregon, Colorado is a vote-by-mail state.

Small eastern Oregon counties with fewer than 5,000 voters typically have a single election employee, while the majority of Oregon counties with between 5,000 and 100,000 voters average two employees. Those medium-sized counties also struggle to afford some tools, such as ballot-sorting machines and computerized signature verification, that could make processing elections easier.

Harney County Clerk Dag Robinson told lawmakers the eastern Oregon county with about 5,700 registered voters is trying to come up with millions of dollars for a new correctional facility. The county doesn’t have money to spare for his request for a part-time election worker.

More funding from the state, federal and local governments would help counties cover the costs of elections, he said.

“It’s just not a level playing field for what our resources are, and we strive to ensure that each voter in Oregon is treated exactly the same,” Robinson said. “We want to make sure that everyone has the same opportunity, the same ability, and without a stable funding stream there’s a risk that we don’t have that.”

Paul Gronke, director of the Elections & Voting Information Center, said there are opportunities for the state to provide resources. For instance, Illinois used a portion of its federal election grant money to make sure each local election office had the cybersecurity and technical training it needed.

“It’s really an equity concern to get all these offices to a point where they can deliver all their services,” Gronke said.