By Oregon ArtsWatch

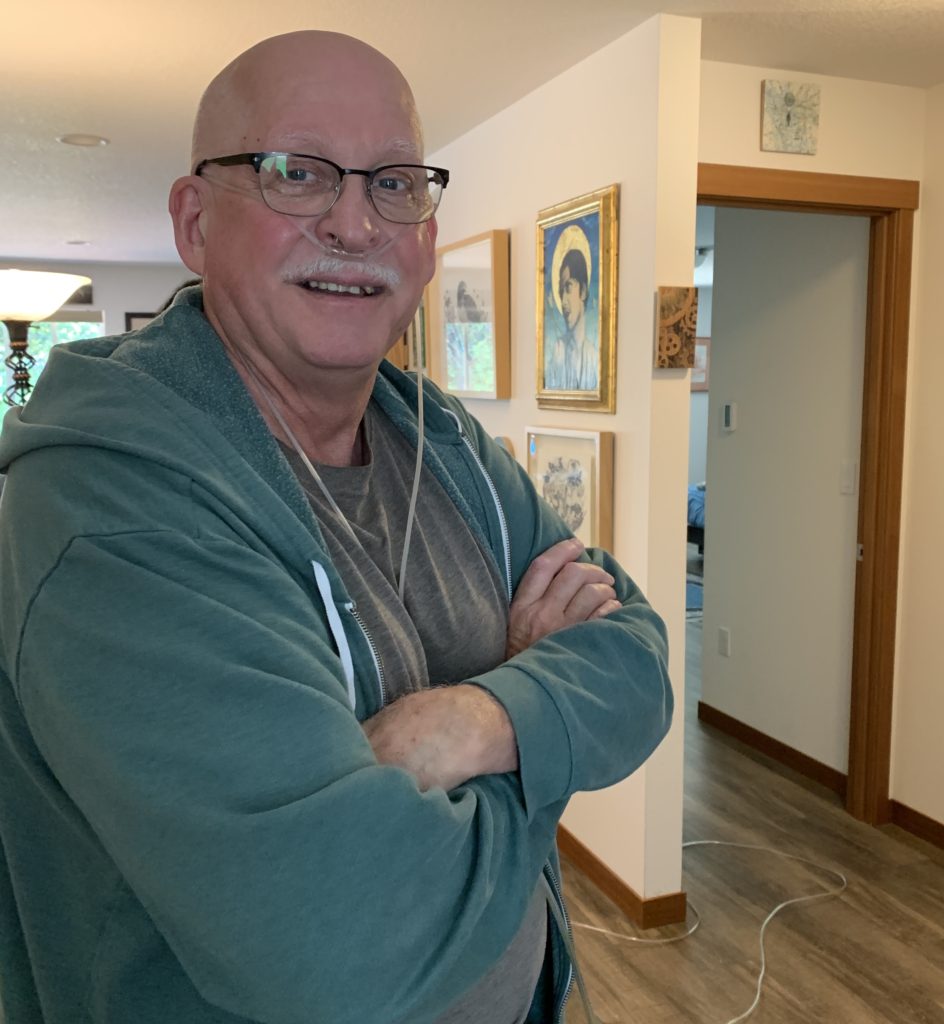

WALDPORT — No one wants to hear they’ve been diagnosed with the illness that will kill them. That includes art collector Duane Snider of Waldport.

Yet not long after doctors gave Snider the grim news, he found himself living some of the most fulfilling days of his life.

“I thought having left Portland, I had been cut off, disconnected, that no one would care,” said Snider, who moved to Waldport in 2018. “But when I got the diagnosis and put it out there, I got this flood of concern and care and well wishes. I never felt so loved and appreciated at any other point in my life.”

As it turns out, Snider’s illness is now believed to be treatable. Still, there’s nothing like a reminder of your mortality to jumpstart that important project you’ve been putting off.

In this case, that would be the cataloging and future curating of the more than 240 works of art – largely by Oregon artists – that Snider has collected since 1982. That task is in the hands of Tammy Jo Wilson and Owen Premore – co-founders of the nonprofit arts organization, Art in Oregon.

“The singular things that are unique about the collection (are) the length of time it covers for Oregon artists in such a wide scope,” said Wilson, who with Premore tackled the project this summer. “And just Duane’s own collector voice as far as leaning toward the surreal, kind of magical, but then also just wanting to capture the Oregon art feeling and artists that are important to the state as a whole.”

Wilson and Premore recalled encountering Snider many years ago at exhibits all over Portland. He was unpretentious, curious, sincere and “just so grateful to have someone sit down and talk with him.”

If “grateful” seems an odd choice of words for a man who has been part of the arts scene for decades. It might help to understand that Snider has also been, in his own words, an outsider.

A common man in art world

In the famously exclusive art community, Snider is the oddity – a man who worked for a living, possessed limited disposable income, and yet managed through sheer will and tenacity to amass not only an impressive art collection, but an estimable education.

And it all started with a chance encounter in 1982 as he walked with his soon-to-be wife, Linda Dies, in their southeast Portland neighborhood. There, he ran into Jackie West, owner of the newly opened Graystone Gallery on Hawthorne Boulevard. The two had become friends during Snider’s years at Menucha art camps, where West was on the Menucha board of directors. West invited the couple to stop by the gallery.

“I had never even been in a commercial art gallery before, so this was all new,” Snider said. “After looking around for a time, my attention landed on this beautiful life-like rendering of an iris. It hit me that it was unique, there may be others like it, but none exactly like it. In the middle of this revelation, a voice from behind me said, ‘You know, we do lay away.’ ”

Four hundred dollars and several months later, Snider and Dies hung the wash watercolor by Kirk Lybecker in their apartment.

“It was a slow but steady windup from there,” Snider said.

He began going to openings and exhibits, attending upward of 45 events monthly and soon earning a reputation for being everywhere that mattered. Art became Snider’s lifeline. Where once he’d turned to drugs and alcohol to combat the depression that came from the drudgery of a production job in an optics lab, now art became his drug.

“I just got completely addicted to the whole panache and going to gallery openings, hanging out with the rich folks,” Snider said. “That has colored my beliefs, viewpoint, outlook more than most anything else. The art world is designed to keep the common man out of it. I am proof that art is for everyone and not just for the highly educated, the rich. Art touches all our lives. Art is the thing that separates us from every other creature on earth … the ultimate expression of who and what we can be.”

Early on, Snider collected ceramics because they were accessible and affordable. But as he was able, he began adding works from numerous mediums. In time, his collection grew to include Todd Walker, Jock Sturges, Holly Andres, Katherine Ace, Kevin Kadar, Zoe Keller, John Frame, Frank Boyden, Terry Toedtemeier, Robert Nelson and Jose Sierra and on and on and on.

Today the paintings, sculptures, photographs, books and pottery color the walls, shelves, nooks and crannies in the open-floor plan home designed for a comfortable retirement, easy entertaining and, of course, to showcase the art.

“One of everything”

The work reflects the description Snider adopted as his own after at a talk by former Portland Museum of Art curator Bruce Guenther.

“He said there’s basically two kinds of collectors,” Snider recalled. “There’s the one that’s really focused that picks out one or two artists and goes very deep into their careers. There is the other kind that is a stamp collector that just wants one of everything. I am a stamp collector. I have paintings, sculpture. I know an awful lot about ceramics. I learned by buying and living with it. I like stuff that is highly detailed. That’s one common thread.”

His attraction to the meticulous and intricate led him to becoming one of the first, if not the first, patrons of Chuck E. Bloom, known for his surreal depictions of structures. There are 33 of his works coloring the walls of Snider and Dies’ home.

“He is one of the most under-appreciated artists I’ve ever met,” Snider said. “His meticulous attention to detail, the repeated use of different elements and the infinite number of combinations … To my mind, the title he gives to the piece itself completes the piece, gives the viewer something to grab on to. One of my great goals in life is to get that body of work into the Hallie Ford Museum” in Salem.

Bloom was one of several artists who made the trip to the coast for Snider’s 70th birthday party in August – the balloons from the celebration still bobbing in the sun lightened house days later.

“Literally, this was the first time in my life anyone threw me a birthday party,” Snider said. “It has turned out to be one of the most life affirming experiences I’ve ever had.”

At the party, Premore recalled, Bloom mentioned how supportive Duane was of his artwork and credited Snider with being a huge motivator towards becoming the artist he is today.

“Duane rarely buys art without first meeting and ideally getting to know an artist,” Premore said. “This is a value he holds dear.”

Although photographs make up just a fraction of Snider’s collection, they are some of the most important. Like most pieces in the house, they come with a story.

There’s the Holly Andres photograph destined for the trash until Snider spoke up, and the Todd Walker piece, a first edition print of a possible 20-print edition. One of the first digitally manipulated photographic fine arts pieces, it was created by Walker, who, pre-Photoshop, wrote a program to digitize a photograph, then digitally painted it pixel by pixel.

One of the most haunting pieces in the collection is a black and white photograph by John Frame of a sock monkey poring over a large book.

“It caught me because it’s a sort of metaphor for kind of what is happening in the world right now,” Snider said. “This being looking down on the world on all this information and not having any idea what it really means. I think it is one of the most enigmatic and mysterious images I’ve ever been drawn to. And I’ve got some mysterious and enigmatic images in my collection.”

Snider doesn’t talk about the monetary value of his collection, though if pressed, say for insurance purposes, he guesses it’s worth triple what he paid. But to him, the real value has nothing to do with money.

“The value is in the quality of the connection it helps you find within yourself and how it helps you find your own unique identity, what you believe in. It should not be about finding design pieces that match your curtain and couch.”

Wanting to share his collection

The question of what will become of Snider’s collection remains a “work in progress.” But with Wilson and Premore on board to catalog and curate it, he no longer worries it could be lost to “Goodwill.com or Storage Wars.

“Being on the inside and being an outsider the whole time, my goal is to get more art into the hands of people who might not think of having a piece of original art,” Snider said. “I want to give people that experience.”

Wilson has two goals: to honor Snider’s intentions, but also to see the collection exhibited in order to inspire others to be patrons of the arts, to understand how valuable it is to live with artwork and how it can contribute to our lives.

“I think for me the ideal would be to do some exhibitions to really have that conversation in a more public way so they could see kind of the unique character of the collection and how the works to talk to each other,” Wilson said. Exhibits could also help heighten appreciation for the Oregon art scene, as well as documenting 38 years of art purchasing within that scene.

Early this year, Snider’s life was shadowed by uncertainty, frustration, disconnection – the sense that having left Portland “no one would care.” But today, having experienced a surprising show of kindness and appreciation, as well as news that word of his impending demise was a bit hasty, Snider is – again – grateful. Abundantly so.

“A lot of what we’ve done here, accomplished here, made going through this whole nightmare of facing my death a whole lot easier,” Snider said. “Where we live and how we live is the most accomplished creative statement I’ve made in my life. I was able to face the prospect of death without any real regrets. All the things I believed art could do for a person they’ve done for me. If that isn’t the point of my life, I don’t know what in the hell is.”

- This story was originally published by our community partner Oregon ArtsWatch. It is supported in part by a grant from the Oregon Cultural Trust, investing in Oregon’s arts, humanities and heritage, and the Lincoln County Cultural Coalition. For more arts news coverage go to Oregon ArtsWatch