By QUINTON SMITH/YachatsNews.com

WALDPORT – It may have been Louis Southworth’s unveiling, but it was Jesse Dolin’s doing.

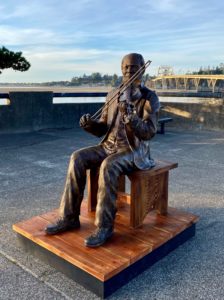

Eighteen months after he suggested to the city of Waldport that it name a big, new downtown park after Louis Southworth, Dolin helped unveil the life-sized statue of the former slave who bought his freedom and homesteaded along Darkey Creek just east of Waldport in the 1880s.

The statue was revealed in ceremony attended by 150 appreciative people under bright November skies Saturday at the Alsea Bay Bridge Interpretive Center, where it will sit until the park is completed in 2-3 years.

Dolin grew up in Waldport, still lives nearby and works for the Oregon Coast Visitors Association, a regional arm of Travel Oregon, the state’s tourism promotion agency. Dolin was the one who brought to local prominence Southworth’s history in Waldport, suggested the city honor Southworth’s legacy by naming the park after him, and then got Travel Oregon to pay for the statue.

“The day I learned of his story was the day they took down the Darkey Creek road sign … one of the unfortunate names given to him,” Dolin, who grew up near the creek, told the crowd. “Why hadn’t I heard of his story before?

“Slavery is a hard history to accept,” he said.

The statue and park are now one way the Waldport community is remembering Southworth, his remarkable story and his contributions to the community more than 125 years ago.

“It’s an incredible honor to shed light on Uncle Lou’s life,” Dolin said, repeating a term for Southworth often used by turn-of-the-century newspapers.

Southworth’s life is in the spotlight because of Dolin’s idea, the park’s new name and the work by bronze sculptor Pete Helzer, who spent months creating the statue in his Dexter, Ore. foundry.

“From the very beginning it was an honor to engage in this project,” Helzer said. “The more I read, the more I became motivated on this sculpture.”

Southworth’s history

Southworth was born in Tennessee on July 4, 1829, according to census records, or 1830 according to his gravestone. While his father’s last name was Hunter, he was born into slavery and therefore given the surname of his master, James Southworth.

James Southworth brought Louis, then 24, and his mother to Oregon in 1853. Within a year Louis Southworth was in the southern Oregon and California gold fields, where he was able to earn money playing music. By 1859 he had saved $1,000 to buy his freedom, eventually settling in Buena Vista northeast of Corvallis where he worked as a blacksmith and ran a livery stable. There he met and married Mary Cooper, who had a son Alvin McCleary.

In 1880, the family staked claim to 40 acres of land on a creek feeding into the Alsea River a few miles east of Waldport. Besides working his land, Southworth also ferried passengers and cargo up and down the river and across the bay.

In 1883 Southworth donated half an acre of land on Alsea Bay for the construction of the area’s first school and later served on the school board.

Locals named the stream along which he lived Darkey Creek. In 2000, the Oregon Geographic Names Board changed the name to Southworth Creek, but it took years before the Forest Service changed the name of Darkey Creek Road.

Mary Southworth died in 1901, and in 1910 Southworth sold his land and moved to Corvallis. He married again in 1913, but by 1915 he was struggling financially. The community rallied to support him, collecting enough money to pay off his mortgage and petitioning the government for a soldier’s pension for him. He died in 1917 before that effort had made its way through the bureaucracy.

Southworth in context

With Southworth’s story getting better known, one of Saturday’s three speakers said it was important to put his remarkable life in context of Oregon in the 1880s.

Zachary Stocks, executive director of Oregon Black Pioneers, said the picture used by Hezler to create Southworth’s statue was taken in 1915 by John Horner, an anthropologist at Oregon State University who studied human skulls stolen from Native American graves to find proof of racial hierarchies.

“Why would this anthropologist take photos and write an article about Louis Southworth? Stocks asked. “I can’t help but think of the staged images of Indigenous peoples that anthropologists and photographers used to document the tragedy of the supposedly ‘vanishing’ Indians. It seems to me that Horner was making a similar documentation of Louis. No one was suggesting that Black Americans were disappearing from Oregon in the 1910s – in fact, Oregon’s Black population was the highest it had ever been — but Louis represented something different. He too, was the last of his kind — the last of the enslaved Oregonians, the last trace of the ‘Old South’ which had emigrated west during the pioneer days.”

Stocks said at the same time Horner’s article about Southworth was printed in The Oregonian newspaper, “Oregon voters rejected a ballot measure to repeal the state’s ban on interracial marriage, and rejected a measure to remove the Black exclusion language from the Oregon Constitution, even though it was no longer legally enforceable.”

Stocks also said Southworth’s time in Oregon spanned the most transformational moments for Black Americans in the state.

“… around the year Louis Southworth was born, York the first Black person to reach Oregon by land, died likely less than 200 miles away,” Stocks said. “The year Louis Southworth died, Mercedes Diez, who would go on to become Oregon’s first Black judge in the 1970s, was born.”

Southworth, he said, was a link in the chain of notable Black Oregonians that stretched from 1770 to 2005.

“No doubt, Louis Southworth was a remarkable individual, but his story is not an individual story,” Stocks said. “It is the story of every 19th century Black American who made a life for themselves in Oregon in the face of legalized inequality. And it is the story of those who fought against that inequality, because they recognized the goodness in those who were different from them. Our ancestors knew that ordinary people could make a difference in the fight for racial justice, and that all of our participation is required in the construction of a more inclusive society.”

Stocks said he was very proud of what the Waldport community was doing to honor Southworth.

“He was probably the most well-known Black in Oregon during his lifetime,” Stocks said. “Louis represented something different. He was the last of enslaved men.”

- Quinton Smith is the founder and editor of YachatsNews.com and can be reached at YachatsNews@gmail.com

-

To read YachatsNews’ original story about Louis Southworth, go here

-

To read a story about Pete Helzer’s work on the Southworth statue, go here

-

To read about the city of Waldport’s plans for Southworth Park, go here