By OSU NEWS SERVICE and OREGON CAPITAL CHRONICLE

The U.S. Department of Energy has awarded $25 million to eight groups for the testing of wave energy technologies at Oregon State University’s PacWave South facility off the central Oregon coast between Waldport and Newport.

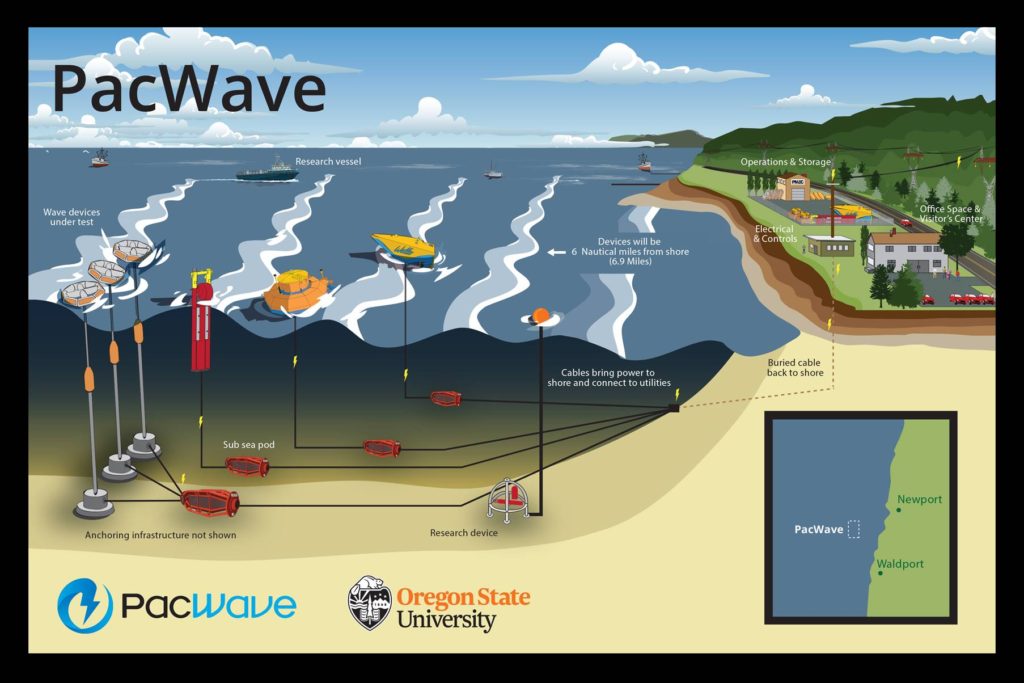

Construction began in June 2021 on the approximately $80 million facility, to be located about seven miles offshore. When completed, PacWave South will be the first commercial-scale, grid-connected wave energy test site in the United States. It is expected to be operational in 2023, and grid-connected testing is anticipated to begin the following year.

“The DOE’s announcement represents an exciting new development in the pursuit of producing renewable energy from ocean waves,” said Oregon State’s Burke Hales, PacWave’s chief scientist. “This commitment to in-water testing at the PacWave site is the bridge from conceptual or scaled-down designs to operational power production in the fully energetic open ocean. It also shows the agency’s long-term commitment to the completion and operation of the PacWave test facility.”

The funded projects will focus on wave energy converter designs for use in geographically remote areas or on small grids; converter designs that can be either connected to or disconnected from the grid; and research and development related to environmental monitoring, instrumentation systems that operators use to control wave energy converters, and other technologies.

Portland State University, with a $4.5 million award, is among the funding recipients. Others include the University of Washington, which is receiving $1.3 million; CalWave Power Technologies Inc. of Oakland; Columbia Power Technologies Inc. of Charlottesville, Va.; Dehlsen Associates of Santa Barbara; Oscilla Power Inc. of Seattle; Integral Consulting of Seattle; and Littoral Power Systems of New Bedford, Ma.

The Department of Energy and Oregon State entered into a partnership in 2016 to build the PacWave South facility for exploring how to harness the carbon-free wave energy created from wind blowing over the surface of the sea. PacWave South, prepermitted by the DOE, is designed to alleviate the challenges associated with testing technologies in the open ocean.

The universities and companies will be the first round of projects tested at PacWave, a new wave-energy test facility off the central Oregon coast that was developed by the federal Energy Department, the state of Oregon and Oregon State University.

Portland State University engineering professor Jonathan Bird is teaming up with engineer Bertrand Dechant and Alex Hagmüller, president of Portland wave energy startup AquaHarmonics. They will develop buoys that can sit atop and move with waves, gathering their momentum and converting the energy into a higher speed motion that gets sent through undersea cables to an onshore or offshore transmission center and then off to a local electrical grid.

“The sea has a lot of energy but the motion is very slow,” Bird said.

The buoys work as a wave energy converter, amplifying the speed of the wave energy with magnetic gears and springs.

“In order to cost effectively generate electricity from the sea you need to come up with a way to convert the low speed motion the sea makes into a higher speed, bigger motion,” Bird said.

A handful of European companies are testing similar buoys, but Bird said they suffer a fatal design error. They use mechanical or hydraulic springs, which could need maintenance or break under massive wave pressure and storms.

With magnetic gears and springs, the buoys should be able to withstand inclement weather and not need maintenance, Bird said.

“You design it like a satellite – put it out there and hope it keeps operating,” he said.

The weather off the Oregon coast will be the biggest challenge to wave energy generating projects, according to Hales. The deep ocean waves off the coast near Newport can be brutal.

“We always say, never put anything in the ocean that you really want back,” Hales said. He also said the infrastructure needs to be simple and be able to function around the clock without interference. “The ocean does not like complicated,” he said.

The future of wave energy for electricity is still distant, according Hales, and it is still not cost competitive with solar or wind power.

But about 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a coast, according to the United Nations. This is what Bird thinks about when he thinks about his buoys and the future of wave energy.

“If we could somehow harness it, it could be very beneficial to a large population,” he said.

Construction on the PacWave testing facility began in June 2021, and is scheduled to completed by 2023. It consists of anchors seven miles out to sea southwest of Newport that connect via undersea cables to a facility three miles north of Waldport, then to a transmission center to connect to the Central Lincoln Peoples Utility District grid.

The projects receiving the federal funding will be tested at PacWave in 2024.

Hales said it could be 30 years before wave energy becomes a viable source of energy in Oregon, but each year they wait to do the research makes that an even more distant reality.

“We’re 20 years behind wind,” Hales said of wave energy technology, “and we think the testing bottleneck is the reason for that.”

- Alex Baumhardt of the Oregon Capital Chronicle contributed to this report

“It won’t be extracting or transmitting energy from the waves,” he said, “It will be the Oregon coast in the winter time.”

If its chief scientist says the project won’t be extracting or transmitting energy, what exactly is it for?