By KRISTIAN FODEN-VENCIL/Oregon Public Broadcasting

Simply getting aboard the Essayons is a hairy proposition.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge ship stretches the length of a football field and surges through the surf. To reach it, a motor launch pulls alongside, matching the Essayons’ speed, and two enormous hooks are attached. Then the whole launch — passengers included — is hoisted up and out of the water.

“In the unlikely event someone falls into the water, if you see it, you shout: ‘Man overboard!’ and point,” the safety instructions flash back to mind.

Ocean-going transportation is key to Oregon’s economy. For bulk products like wheat and cars, there is no more efficient way to get goods to market. Last year, $22 billion worth of cargo was shipped through Pacific Northwest waterways.

But sand silts up many rivers, including the Columbia, making them dangerous to navigate. That’s where the Essayons comes in, dredging up sand to maintain a 43-foot-deep navigation channel. During this time of the year, it’s working along the Columbia River Bar, a treacherous stretch at the mouth of the river known as the “Graveyard of the Pacific.”

Some 2,000 vessels have met their demise here, where the river meets the ocean.

The problem is the mixture of bad weather, complex ocean currents, large volumes of water flowing out the Columbia River and massive Pacific Ocean waves that have been building momentum for 3,000 miles.

“It gets dangerous, especially when the tide gets low,” said Steven VanHorn, a second mate on the Essayons.

From the bridge, seven stories above the water, VanHorn is surrounded by maps, compasses and computers. It’s his job to control two enormous dredge arms that hang over the sides of the ship.

The arms drag along the ocean floor, sucking up sand like two enormous vacuum cleaners. They empty into cavernous holds on the vessel causing the whole ship to gradually — and rather ominously — sink toward the waterline as it fills.

The Essayons heads to the Columbia Bar during the fall because the weather is comparatively calm, and the dredging is less likely to disturb migrating salmon.

But in October and November the winter storms start rolling in.

“One of the main rules of dredging is you always have to be making headway,” VanHorn said. “If you go backwards, you could break a drag arm. And when those swells get big enough, sometimes you go up a swell and come back down the other side. That will make you slide backwards.”

When that happens at full power, it’s time to pack up for the year.

Some of the wrecks that speckle this area have long since been taken out of the 600-foot-wide navigation channel, so that’s no longer a problem for the dredge arms. But like vacuum hoses at home, they can get blocked. Around the bar, it’s usually just with large pieces of wood or rocks.

“But when we were digging in Pearl Harbor we would get some ammunition and unexploded ordnance from World War II,” VanHorn said.

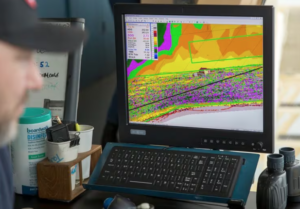

Old weapons aren’t an issue along the Columbia Bar, so VanHorn spends his days in front of a bank of computers, guiding the dredge arms to high spots along the channel. Red warning dots on his screen turn green as the sand is sucked up.

“It’s basically like a little video game,” VanHorn said, laughing. “It’s not as easy as PacMan though.”

It’s own, small city

Over his shoulder, Capt. James Holcroft watched, sipping an enormous cup of coffee. He’s been top dog at the 350-foot Essayons for 20 years and likens the job to being mayor of a small town.

“It’s basically a small floating city,” Holcroft said. “We have our own hospital. We have our own fire department. We have our own security force. I have my own electricians. [We] generate our own power. We have our own environmental system for sewage treatment and water treatment. Everything a small town would have, we have it here.”

The 25 crew members live on board for two weeks at a time, working 12-hour shifts so dredging can continue round the clock.

There’s a galley and a weight room, but not much else for entertainment.

After 40 years on the water, Holcroft isn’t overly concerned about the Columbia Bar, although he concedes it can get disconcerting when the vessel dumps sand near the beach through the massive holes in its hull.

“Sometimes, when we open the doors, some of the material stays in there a little bit longer, so the ship will heel over 20 to 25 degrees,” he said. “And we’ll be heeled over, working in the surf. And normally you don’t see a ship this size heeled over in the surf that’s not in trouble.”

Over the years, several people have called 911 to report problems with the Essayons.

“But that’s just our job,” he said, laughing.

The floating city isn’t always floating off the Oregon coast. During different times of the year it sails to different locations — to hit environmental windows for endangered species.

In the spring, the ship dredges in Grays Harbor, Wash., working around green sturgeon. In summer, they head down to San Francisco Bay, working around smelt runs. Fall means avoiding endangered salmon along the Columbia River Bar.

But as soon as the first big winter storm rolls in, the Essayons will head back to the shipyard for five months of winter repairs.

- YachatsNews is a news partner with Oregon Public Broadcasting, where this story originally appeared Nov. 3.