By QUINTON SMITH/YachatsNews.com

and GARY A. WARNER/Oregon Capital Bureau

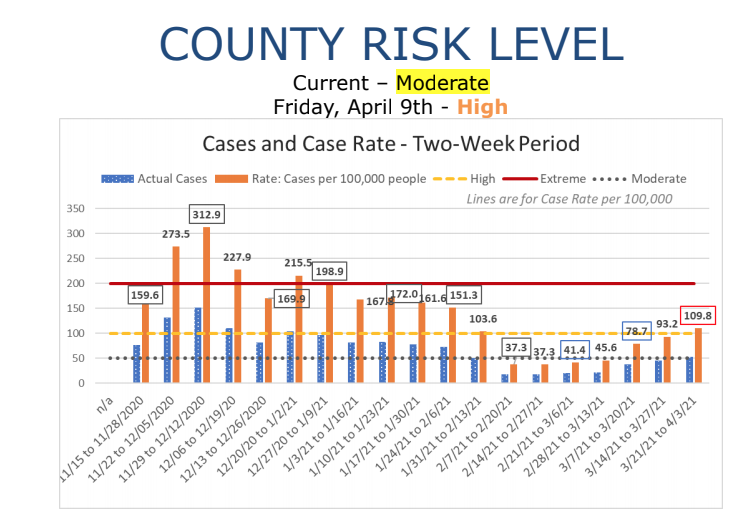

A month-long rise in COVID-19 cases is moving Lincoln County into the state’s “high” risk category Friday, tightening social and business restrictions that only four weeks ago were one of the loosest in Oregon.

Lincoln County is one of five across Oregon moving from “moderate” to “high” Friday as the number of cases increase across most of the state. It was only two weeks ago that the county moved from “low” to “moderate.”

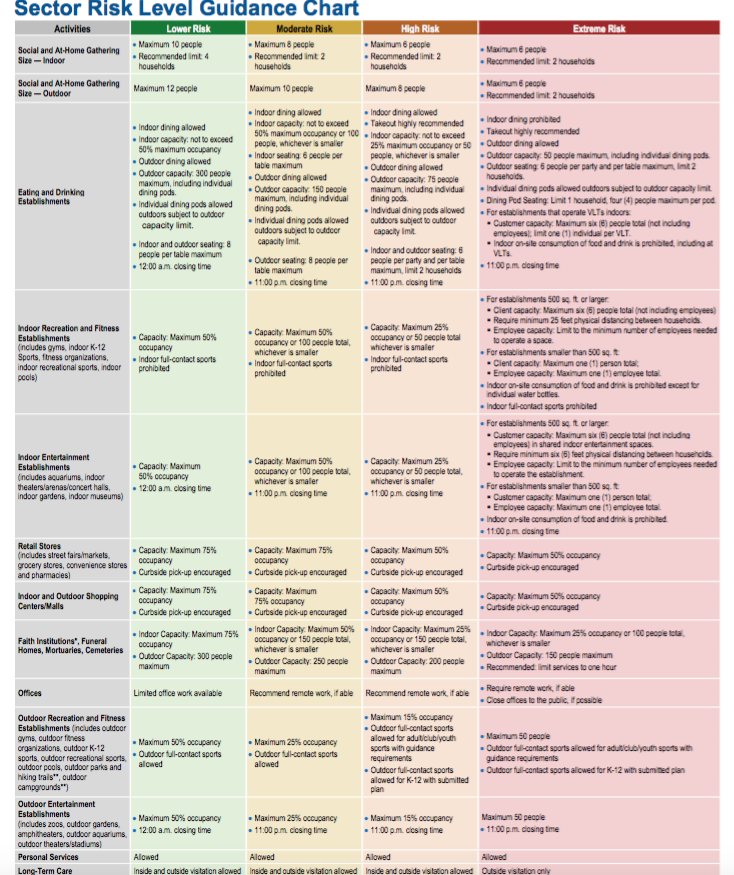

While the “high” risk ranking means restaurants and bars can continue with indoor dining, they are supposed to restrict capacity to 25 percent, half of the current 50 percent capacity. The same is true for indoor entertainment like theaters and aquariums.

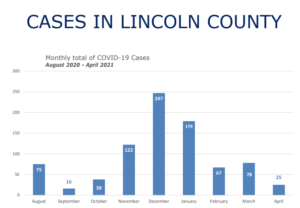

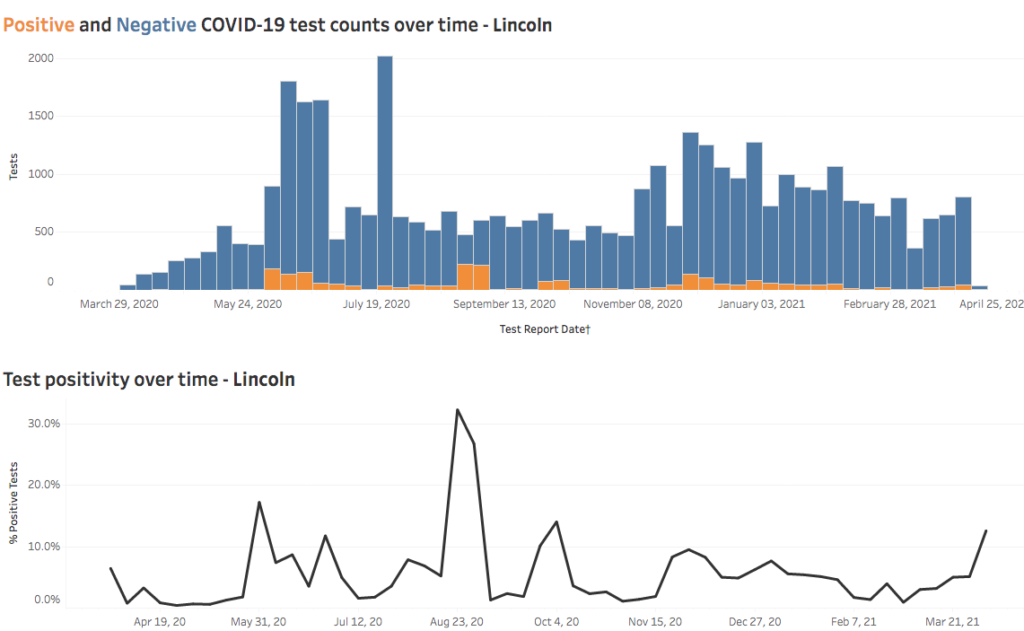

As of Tuesday, there already have been 28 new cases reported in Lincoln County this month, one-third of the number in all of March. But it was the number of cases between March 21 and April 3 that pushed the COVID-19 rate over the 100-case-per-100,000 population threshold and into tighter restrictions. Twelve of this month’s cases occurred among Lincoln County Jail inmates and staff.

The change comes as Lincoln County Public Health and its health partners vaccinate residents at one of the fastest rates in Oregon. It has given first or second doses to 20,000 people of the 28,000 to 30,000 county residents expected to want them. Clinics this week are scheduled to deliver another 2,200 first doses and 1,200 second doses, according to LCPH.

The county is already inoculating front-line workers, their dependents and people with health issues ahead of the state’s schedule. It also vaccinated more than 500 seafood workers and fishermen during special clinics last week on the Newport bayfront, and is working with other groups conducting clinics aimed its Hispanic and indigenous residents. The Confederated Tribes of the Siletz also reported Monday that it had vaccinated 5,000 members of its tribe and the general community.

Health officials said the increase in numbers was due to an outbreak at the county jail which affected eight inmates and two staff and from employees of several restaurants. In addition to getting vaccinated, officials urged residents to keep wearing masks, continue to social distance and wash or sanitize hands.

“We’re definitely headed in the wrong direction,” said LCPH deputy director Florence Pourtal.

Is the U.K. variant here?

On Tuesday, Gov. Kate Brown – following a directive from the Biden Administration – dropped all eligibility restrictions for getting vaccinated beginning April 19. That’s two weeks earlier than planned.

Oregon had previously planned to drop all eligibility restrictions by May 1, with some counties possibly offering appointments as early as April 26.

“We are locked in a race between vaccine distribution and the rapid spread of COVID-19 variants,” Brown said.

Until April 19, Brown said Tuesday, Oregon would continue to prioritize vaccinations for people with underlying medical conditions, essential workers, and communities underserved during the pandemic.

The move comes as infections and hospitalizations have started to rise after a long decline since January. The state has reported over 400 cases per day in the past week and has seen rising numbers of hospitalizations, despite having fully vaccinated over 777,000 of the state’s estimated 2.8 million adult residents.

An Oregon Health & Science University forecast released last week estimated the current spike will lead to an average of 1,000 cases per day by next month.

Evidence of the virus rebound was also found in the latest infection risk level ratings for Oregon’s 36 counties, issued Tuesday. After a steady trend of counties moving lower in the four-tiered risk ratings, the report this week showed a number of counties with infections on the rise, requiring a return to tighter controls on activities, gatherings and dining.

While COVID-19 deaths have continued to stay lower than previous peaks, health officials have remained concerned about possibly more virulent variants of COVID-19 spreading across the country and into Oregon.

The CDC has singled out one variant originally found in the United Kingdom — B.1.1.7 — as the main version of the virus hitting about two-thirds of the country. The Oregon Health Authority has reported 19 cases of the U.K. variant in Oregon, but believes there are many more.

Lincoln County sent six COVID-19 tests conducted last week to the Oregon Health Authority lab in Portland to see if they are the U.K. variant.

“Because of the increase here, we’re worried that the variant might be here,” LCPH spokeswoman Susan Trachsel told YachatsNews on Tuesday. “It’s in every state.”

The other concern of Lincoln County health officials is that the positivity rate of local COVID-19 tests has ballooned to 12.5 percent – the highest rate since October. It had been below 1 percent in late February.

Vaccine supply an issue

Brown and OHA Director Pat Allen have said the greatest impediment to widespread inoculation is supply of vaccine. Over the past week, Oregon has questioned the federal allocation process state officials believe could be short-changing the state on vaccine allocations.

“My office will work closely with the White House to ensure Oregon receives our fair share of federal vaccine supplies, so we can continue with a fast, fair, and equitable vaccine distribution process,” Brown said.

Oregon health officials said there have been more than 2 million doses of vaccine delivered into the arms of Oregonians. Most of the shots are for the two-dose Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

The one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine has accounted for just over 50,000 shots in Oregon. It remains in limited supply nationwide due to a botched processing system at a subcontractor in Baltimore that ruined 15 million batches that had to be destroyed. Doses currently offered are the correct mixture.

Several weeks of falling infection numbers had led the state to relaxing limits on eating at restaurants, holding public events, and limiting the number of customers allowed in businesses at one time.

The rise in numbers will lead to the return of some restrictions. Brown announced on Tuesday that the most extreme limits would only go into effect if more than 300 Oregonians with COVID-19 are hospitalized and the number increases 15 percent or more over a 7-day period.

As of Tuesday, Oregon hospitals reported 205 patients with COVID-19.

The rankings for all counties

Under the new rules, three counties qualify as extreme risk, but will be at high risk restriction levels: Josephine, Klamath, and Tillamook. Baker, Columbia, Lane, Polk and Yamhill counties are in the two-week caution window allowed when a county drops into a lower level, only to rebound in the next period back to a higher rate. They are allowed two weeks to reverse the trend before higher restrictions are applied.

Fifteen counties are in the lower risk category: Baker, Crook, Gilliam, Grant, Harney, Hood River, Jefferson, Lake, Lane, Malheur (moved from moderate), Morrow, Sherman, Wallowa, Wasco and Wheeler.

Seven counties are moderate: Clatsop, Columbia, Polk, Umatilla (moved from high), Union, Washington, and Yamhill (moved from lower).

Eleven are in the high risk category: Benton, Clackamas (moved from moderate), Coos: (moved from extreme), Curry: (moved from extreme), Deschutes: (moved from moderate), Douglas, Jackson, Marion, Lincoln (moved from moderate), Linn (moved from moderate), and Multnomah (moved from moderate).

Three are extreme: Josephine (moved from high), Klamath (moved from moderate), and Tillamook (moved from moderate).

Breakaway cases are at 164 for the state after vaccines with 3 deaths through April 4. Wear your mask, do as you have been doing. Just because you’re vaccinated doesn’t mean its 100 percent.

And yet the push is on for schools to be all in person. The district hierarchy claims it doesn’t spread in schools, but it’s easy to say when children have not been crowded together, studies say otherwise, and schools as close as Albany are having issues. One could easily look at the information and see that staff and students have already tested positive. Many issues exist in this erroneous endeavor including bending the expectations to fit the situation (the Ready Schools, Safe Learners states that middle and high school students must be at six feet distance when cases are as high as they currently are). The push to put children in buildings for the final eight weeks will not improve their learning as staff are required to be six feet away. Children must take turns eating and watching others eat in many classrooms in order to follow protocols. Bussing will most likely not maintain distancing measures. Are we so certain that the leadership of the district has the best interest of the students and staff at heart when they keep themselves separated and haven’t the slightest clue about the real situation at hand?