By GARY A. WARNER/Oregon Capital Bureau

and QUINTON SMITH/YachatsNews.com

The record wave of COVID-19 cases in Oregon and Lincoln County appears to have crested, but the long recovery will likely stretch into the winter holiday season.

“I’m happy to deliver some promising news — daily cases and hospitalizations are slowly coming down from record highs,” said Dr. Dean Sidelinger, the state epidemiologist, during a Thursday call with reporters.

New infections and deaths also remain high but are trending down the past two weeks after eight weeks of rising numbers driven by the highly contagious delta variant. But it will take as long to get down from the crest as it took to get there, about two months, according to state forecasts.

“The Delta variant remains a formidable threat,” Sidelinger said.

With more than 1,000 COVID-19 hospital patients statewide — nearly all unvaccinated — hospitals are reeling and medical attention is delayed to not just virus patients, but heart attack victims, those injured in car crashes and other life-threatening incidents.

“These capacity levels are not sustainable. Our health system remains under significant stress,” Sidelinger said.

The Oregon Health Authority on Thursday reported 46 new COVID-19 related deaths in the state, raising the overall death toll during the crisis to 3,536. Despite the recent sharp rise in cases, Oregon’s overall per capita death rate ranks 46th among the 50 states.

Cases slowing in Lincoln County

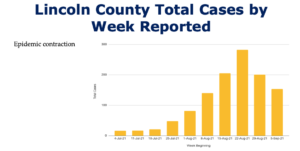

Lincoln County’s acting health director said Wednesday that COVID-19 cases — while still high — and hospitalizations seem to be leveling off. Through the first 15 days of September, the county had 355 reported cases of COVID-19. That’s higher than any month of 2020, but a slower rate than the record 789 cases in August.

“I want to remain cautiously optimistic,” Florence Pourtal told Lincoln County commissioners in her weekly report.

As of Wednesday, there was just one person with COVID-19 hospitalized in Lincoln County but seven local residents in hospitals outside the county, according to the health department. Pourtal said 88 percent of the local COVID-19 cases are occurring among the unvaccinated.

“The unvaccinated are driving cases and hospitalizations,” she said.

Pourtal said she is now watching to see the effect of the start of classes in the Lincoln County School District. On Wednesday in its weekly outbreak report, the Oregon Health Authority reported eight students and one staff or volunteer at LCSD schools had tested positive for COVID-19 between Aug. 31 and Sept. 9. Single cases involving students were reported at Crestview Heights, Yaquina View, Newport Middle, Siletz Valley, Toledo Junior/Senior High, Eddyville Charter and Taft High schools. One staff or volunteer tested positive Sept. 5 at Taft Elementary School.

Better by the holidays?

COVID-19 trend forecasts from Oregon Health & Science University last month held out the possibility that after dropping through September and October, COVID-19 levels could fall to levels not seen since the very beginning of the pandemic. But the latest forecasts show a later and slower decline. Hospitalizations are projected to be below 200 per day by Thanksgiving. Oregon residents should hope for the best, but prepare for the virus to once again impede holiday cheer.

“We’re not fortune tellers,” Sidelinger said. “We will probably all be considering celebrating differently. We may shiver a bit out in the cold.”

The rebound could slow or stall amid challenges from several factors, including Labor Day holiday weekend socializing, K-12 schools reopening to in-class instruction, the return of college students, and major events such as the Pendleton Round-Up and college football games.

“Every opportunity that brings people together is an opportunity for the disease to spread,” Sidelinger said.

The severity of the flu season and the level of wet and cold weather that may cause people to congregate indoors more could also contribute to infection levels.

All are occurring as the state experiences its highest infection rates of the entire crisis, which is now into its 19th month since the first case in Oregon was reported at the end of February 2020.

Sidelinger’s comments came just after the announcement that Reynolds High School in the Portland suburb of Troutdale, the state’s second largest high school, would close for a week because of likely COVID-19 exposure.

Setbacks to in-class instruction were expected, Sidelinger said. He noted the Oct. 18 deadline for school staff to be fully vaccinated. Anyone — teachers, staff, parents, students — who believes they were exposed to COVID-19 needs to isolate and not come to school.

“They are not drivers of infection,” Sidelinger said of schools. “The drivers of infection is the community.”

Following masking and social distance protocols and encouraging anyone who has not been vaccinated to get their shots was the best counterattack. Those who remain unvaccinated, go unmasked and gather in groups are being selfish because their decisions put others at risk, Sidelinger said.

“Come together as a community,” he urged. “Vaccinations work, masks work.”

Fatigue over the warped daily reality of living with COVID-19 can easily set in. But giving in to the fatigue will only give the virus a chance to grow again.

“This is going to be with us through the fall and the winter and perhaps beyond,” Sidelinger said.

Vaccination rates are slowing again, leaving millions of Oregonians without protection. But many of those already inoculated could be eligible for booster shots of vaccine within a month. Those with compromised immune systems are already receiving third shots, a total of 610 people last week. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention committee will meet for two days next week to set policy on booster shots for more people, particularly the elderly or those with medical conditions that make them more prone to severe cases of COVID-19.