By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews.com

For the second year in a row, an open-air laboratory is being nurtured south of Yachats as part of a decades-long effort to save the Oregon silverspot butterfly from extinction.

Building on research conducted last year in fields at Rock Creek and on Brays Point, a mower will roar into action in early June to recreate butterfly-friendly habitat that, due to development and other factors, no longer exists in the wild.

The work was initially scheduled to get underway two weeks ago, but had to be delayed after the machinery’s operator realized the mower and trailer were too big to fit through the access point off U.S. Highway 101 to the meadows. A second contractor, using smaller equipment, has been hired to take over the project.

If the collaborative effort to bring the butterfly back is successful, project managers say, it could start the clock ticking to ultimately delist a species that has been federally labeled as threatened since 1980.

And the key to that success, they add, is understanding how to best manage a mere handful of coastal “salt-spray” meadows that are the butterflies’ only known home on the planet.

“Even in recent years we didn’t want to go too far, too fast, because we didn’t want to accidentally impact the silverspot in a negative way,” said Deanna Williams, head biologist for the Siuslaw National Forest. “But what we have going for us this year is the knowledge to launch into a much larger scale of influencing the entire meadow system, rather than just focusing on individual silverspots.”

Questions and answers

A team of anywhere from 10 to 12 biologists and specialists will be working through late summer, when the butterfly emerges from its caterpillar’s chrysalis, to answer questions such as: How far do the butterflies travel upon emergence? How are larvae responding to climate change, especially increasingly hot and dry conditions? Will more butterflies continue to come out of meadows that have been closely clipped, versus areas not shorn at all?

Another key question burning right now involves the attempt to better understand where wild female butterflies – as opposed to the captive-reared larvae that are also integral to the restoration effort — go after they emerge.

Researchers, wielding Sharpies, marked at least 130 wild butterflies last June, Williams said. Of those, only a handful were females. Then, starting Aug. 5, wild females starting showing up in far larger numbers.

“So where did they go?” she asked. “To interior meadows to find interior flowers? We hope to start to answer that this year.”

Landowners get involved

One new strategy to help answer that dispersal question involves enlisting some of the several hundred private landowners who reside near Rock Creek and Brays Point, said Samantha Derrenbacher, wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Since butterflies were recorded last year at sites within four miles of Rock Creek and Brays Point, she said, landowners living within that distance can sign up to designate a portion of their property for habitat studies this season.

“This is really an effort to get more boots on the ground to look at adjacent meadows that haven’t been really examined in the past,” Derrenbacher said. “We are hoping that a big effort to expand the search range will better help us understand butterfly travel and behavior.”

At least one landowner in the targeted area has recently signed what’s called a “safe harbor” agreement to use a designated piece of his property for study, said Tyler Clouse, a water quality monitoring and assessment specialist with the Lincoln Soil and Water Conservation District.

Such agreements stretch over 10 years, giving researchers considerable time to deepen their knowledge of where the silverspots travel.

The pacts also call for specialists to plant specific pollinating wildflowers, such as goldenrod, fireweed and yarrow, which known to provide food for silverspots, Clouse said.

“The butterflies need early, mid and later pollinating flowers to get them through an entire season,” he said. “This is a great way for us to expand both what they can feed on and where they can find it.”

Additional critical help

Two elements of past efforts to restore the silverspot population will again play key roles in this year’s efforts.

The first is use of butterfly larvae from the Oregon Zoo’s breeding program. Staff there provide hundreds of silverspot larvae each year, which are then introduced into the meadows where native butterflies are known to exist.

Adult females are brought to the zoo, where they lay eggs. The eggs are hatched in special jars and then refrigerated over the winter to match winter conditions on the coast.

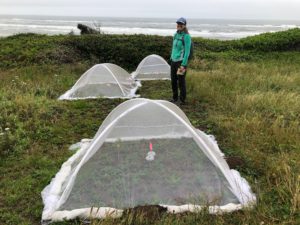

In spring, the caterpillars are taken from their jars and fed with early purple violets – the only known source of food that caterpillar larvae eat. After going through six phases of growth called “instars,” the young pupae are taken from the zoo and placed in protective cages on the coast. Biologists can then monitor their growth daily as they move toward release to join free-flying wild butterflies.

Williams said it’s impossible to overstate the role the zoo’s breeding program is playing in efforts to bolster silverspot populations.

“The zoo is just critical to what we are all trying to do,” she said. “We wouldn’t be where we are without this.”

The second are the caterpillar-tracking detection dogs from eastern Washington that will once again take to the meadows to point out what researchers almost certainly would never find on their own.

The dogs, which are rescue animals and not considered especially suitable as pets, are trained by Rogue Detection Teams to find caterpillar poop, or “frass.” When they find a hit, they wait patiently as researchers scramble over to see what they’ve found.

“It’s the most amazing thing,” Williams said. “We used to think that all we had to do was find some purple violets and watch for caterpillars eating them. What the dogs have taught us is that the caterpillars move around much more than we realized.”

She added, “Without the dogs, we’d be spending a lot of time looking and not seeing a thing.”

A call to action

One new element of this year’s work plan calls for public involvement in everything from attending sessions on how to create backyard pollinator gardens to rolling up your sleeves out in the habitat meadows themselves.

While some scheduling details remain to be ironed out, informational sessions are slated for the Oregon Coast Aquarium, the Newport Farmer’s Market and Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area.

“If anyone wants to get their hands dirty in helping to restore silverspot habitat,” Derrenbacher said, “this is the year to do it.”

In addition to the need for getting additional hands involved, she and other project leaders hope the sessions help the public to better understand why saving one species of Oregon coastal butterflies matters so much.

“The silverspot butterfly is like the canary in the coal mine,” Williams said. “It’s happily singing until something happens and suddenly it dies. It’s there to warn people that something really toxic is occurring.”

The silverspot’s inability to survive in its habitat could well portend the extinction of myriad other species depending on that same habitat, she said.

“Using the butterfly as a platform to care is a way of saying we know there’s something wrong in these habitats and that’s really what we’re trying to fix here,” Williams said. “It’s not just one species that’s at stake here, but countless other ones, as well.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com

-

To read a YachatsNews story about last year’s research, go here

-

To see a Forest Service documentary on its Rock Creek area research, go here