By ALEX BAUMHARDT/Oregon Capital Chronicle

To avoid major lawsuits under the federal Endangered Species Act, state and federal agencies have crafted a plan to reduce the amount of timber logged from Oregon’s western state-owned forests annually by up to 40%. Officials in some counties that have relied on those timber revenues for the past 80 years are angry and worried about the impact that could have on their budgets and social services.

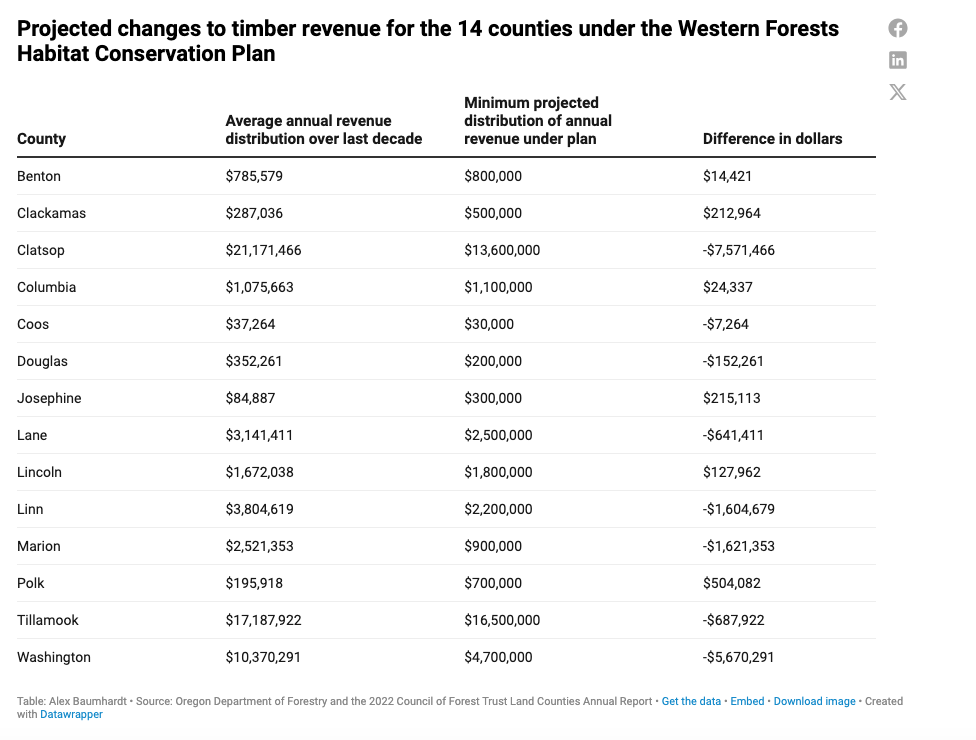

On Monday, the Oregon Department of Forestry released its long-awaited projections showing how much timber revenue each of 14 western Oregon counties would get a year for the next 70 years following the adoption of a landmark proposal that’s expected to be adopted next year. The Western Oregon State Forest Habitat Conservation Plan would govern logging and conservation on about 630,000 thousand acres of state forests to protect 17 threatened or endangered species. The plan awaits approval from the Oregon Board of Forestry and the federal government.

If the habitat plan passes as expected next year, total annual timber revenues to eight counties could decline by as much as $18 million compared to the past decade’s averages, according to the forestry department’s latest figures. Six counties stand to earn thousands of dollars more in annual revenue under the plan, but eight could lose up to several hundred thousand dollars each year. Clatsop and Washington counties appear to be staring down multi-million dollar losses.

The Board of Forestry is scheduled to discuss the projections on Thursday, Dec. 14. Its chair, Jim Kelly, was unavailable to discuss the findings and Mike Wilson, the forestry department’s state forests division chief, declined to comment before the meeting.

Habitat gains

For conservationists, the latest figures show that the forests can still offer plentiful financial benefits to the counties as well as better protection for critical habitat. On average, the counties have received a combined $63.9 million each year during the last decade from logging. Under the new plan, they stand to receive between $46 million and $51 million.

Michael Lang, Oregon policy manager of the nonprofit Wild Salmon Center, said Oregon’s western state forests have been overlogged for decades, and especially during the past 20 years. About 11% of them are considered “complex” or “layered” forest suitable for myriad species, and less than 10% of the original old growth in those forests remains, according to data from the Oregon Department of Forestry.

“We hope they push forward and finalize this habitat conservation plan and the new forest management plan,” Lang said. “It’s looking to the future and not in the past, which is unsustainable.”

But some county leaders say the costs to their budgets under the habitat plan are too high. Courtney Bangs, chair of the Clatsop County Board of Commissioners, said timber revenues fund positions for police, firefighters and teachers. She also worries about jobs in nearby timber mills going away following a dramatic cut to the amount of forest that can be logged.

“Any reach into our pocket has a pretty long lasting and extreme response,” she said.

For Tillamook County Commission Chair Erin Skaar, any revenue loss is too much.

“No loss is acceptable,” she said.

Timber losses

On average, 252 million board feet of wood, or enough to build about 16,000 average homes, has been harvested from Oregon’s western state forests each year for the past 10 years. As part of an 80-year-old deal between the state and the counties where the forests are located, 65% of the revenue from those harvests each year goes back to the counties and smaller “taxing districts” within them – an average of nearly $64 million each year during the last decade. Klamath County state forest land is not covered under the habitat conservation plan, and is thus omitted from the projections.

The state has given Clatsop County about $21 million and Tillamook County an average of $17 million in timber revenues each year during that time. These two counties encompass the largest share of western state forests that are logged, and leaders from both have been the most outspoken against the habitat conservation plan.

While most counties could lose several hundred thousand dollars each year, Clatsop County and its smaller taxing district losses would be the highest – a maximum of $7.6 million per year. Lincoln County would actually see an increase of $128,000 a year.

Clatsop County’s operating budget this year is $98 million. Clatsop County Commissioner Courtney Bangs said the $7.6 million cut would likely curtail the county’s public services, including schools and police.

As an example, she pointed to the Jewell School District, which serves 133 students in Seaside. It runs entirely on about $5 million a year in county timber revenues, rather than the state school fund. Bangs said the school would be gutted.

The Oregon Department of Education, however, said it would step in to fund the school if it lost its timber revenue.

“The funding formula for the State School Fund is designed to take into account changes in local revenue. So, a loss of timber sales would mean that the district would start receiving State School Funds,” Peter Rudy, an education department spokesperson, said in an email.

Most of the counties appear to be facing a smaller impact from lost revenues than previously anticipated. Former Tillamook County Commissioner David Yamamoto had told reporters months ago that the state timber revenue accounted for almost 25% of Tillamook County’s general fund budget and that cuts would be difficult. Under the latest projections, Tillamook County and its taxing districts would lose a maximum of about $688,000 per year. The county’s operating budget for 2023 was more than $145 million.

Skaar in Tillamook County is concerned that the forestry department’s numbers aren’t accurate and that they don’t take into account other potential financial losses from reduced logging. But she acknowledged that the impact appears to be far less than anticipated for her county.

“We are probably one of the least damaged in this,” she said Wednesday.

Still, Skaar said she stands with her colleagues in other timber communities who are concerned about losing timber revenue.

“Every dollar we lose is a service that somebody could lose,” she said.

Promise of passage

The Western Oregon State Forests Habitat Conservation Plan would govern the bulk of Oregon’s Coast Range forests that are managed by the Oregon Department of Forestry. Currently, the state forester can change conservation areas in state forests without agency and public input.

Under the new plan, the state forester would no longer be in charge of such decisions in conservation areas, and some previously logged areas in the forests would be off limits to logging for at least 70 years.

If approved, the conservation plan would protect the state from lawsuits over 17 species that are protected, or expected soon to be protected, under the Endangered Species Act. Among them are Northern spotted owls, marbled murrelets, salmon and steelhead, martens, red tree voles and torrent salamanders.

The Western Oregon State Forest Habitat Conservation Plan itself has been decades in the making. But it was accelerated around 2018 and again this year following lawsuits over species loss in Oregon’s western forests and a settlement this spring between the Oregon Department of Forestry and several conservation groups over logging and endangered coastal coho salmon. Part of that settlement included the forestry department’s assurance that the Western Oregon State Forest Habitat Conservation Plan would be passed.

- Oregon Capital Chronicle is a nonprofit Salem-based news service that focuses its reporting on Oregon state government, politics and policy.