By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews

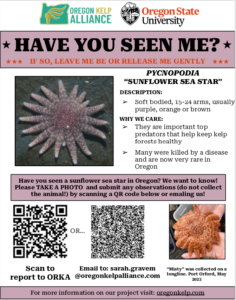

An iconic species of sea star has disappeared in such astonishing numbers along the Oregon coast over the past decade that researchers are now circulating what amounts to a “wanted” poster to help people figure out what to do if they spot one.

Researchers estimate that as many as five billion sunflower sea stars have died since a mysterious “wasting syndrome” began decimating their numbers in 2013.

So it was with surprise and delight recently when an Oregon Coast Aquarium crew discovered 25 of the critically endangered sunflower sea stars on the sandy seafloor of Yaquina Bay.

“To come across not one, but 25 sunflower stars?” Tiffany Rudek, an OCA aquarist, said in a statement. “It’s incredible. It’s unprecedented. I am so excited about what this could mean for the species.”

The group was searching for fish and invertebrates, which the Newport aquarium is permitted to gather a limited number of annually, when the staff documented one adult and 24 juvenile sunflower stars. The largest measured just six inches across.

Rudek has spent the last several years developing a treatment for sea stars impacted by stress, injury, or disease — including those suffering with wasting symptoms. She continues to refine the method, collaborating with marine life groups involved in sea star research efforts.

Fully grown sunflower stars can reach up to four feet across and have as many as 26 arms. That makes them far larger, obviously, than the mussel-eating orange and purple ochre sea stars that populate ocean tide pools, and which have bounced back far faster since the sea star wasting syndrome was first reported off the coast a decade ago.

Scientists still don’t fully understand what caused the outbreak, although possible causes are thought to include a virus, warming ocean temperatures, human impacts or a combination of any or all of those.

The syndrome causes healthy adult sea stars to first show lesions before literally melting into a gooey, broken-limbed mess.

The syndrome has taken such a toll on sunflower stars that Sarah Gravem, a research associate in Oregon State University’s College of Science, said in a 2020 interview with YachatsNews that only seven observations of any sunflower stars off the Oregon coast had been reported by anyone, from professional researchers, to divers, to citizens reporters, in the three prior years.

The coast aquarium’s finding is “great,” Gravem said in a new interview this week, adding that if “people are seeing them, even in small numbers, there are probably more out there.”

But she cautioned against declaring that anything resembling a widespread species recovery is now underway.

“This is one group in a bunch of drip, drip, drips we’ve been getting over the past weeks, months and years,” Gravem said. “These are first steps, certainly, but nothing compared to the billions of sunflower stars that once were everywhere off our coast.”

Why it matters

Any possible bounce back of sunflower stars extends far beyond the excitement of new sightings, she said. That’s because the formally named “pycnopodias” are considered a “keystone predator” of purple sea urchins.

In their absence, urchin populations have exploded, leaving them free to feast on the large, off-shore kelp forests that historically have hosted near-countless populations of marine animals and helped support coastal economies.

Entire swaths of areas once covered by kelp forests have been, in essence, clearcut, as armies of urchins enjoy luxurious meals of kelp without fear of being eaten themselves.

Divers recently counted more than 400 urchins crammed into a single two-by-five-meter patch in the Redfish Rocks Marine Reserve just south of Port Orford.

“Right now, it’s just a buffet for them out there,” Gravem said. “There’s absolutely nothing for them to be scared of.”

A search for answers to what is now a stark imbalance between urchins and sunflower stars is very much on. To that end, Gravem will join other researchers in Alaska next week to dive in the only area off the West Coast that features healthy numbers of urchins, sunflower stars and kelp forests.

One of the group’s goals will be to determine how the presence of sunflower stars in significant numbers affect the feeding habits of urchins. Key questions include how many urchins can a single sunflower star eat? Is the mere presence of a sunflower star sufficient to scare urchins away? If so, will an urchin retreat into a crack in a reef for only an hour? For days?

And, at the heart of it all, how do chemical communications between the competing species actually work?

“Right now, urchins have nothing to be afraid of,” Gravem said. “But what if we do the equivalent of releasing a tiger into a grocery store? People aren’t likely to keep shopping there, are they?”

All of that, she noted, is dependent on the research community’s ability to reintroduce sunflower stars in anything close to pre-wasting syndrome numbers. Jumping from the 25 found in Yaquina Bay back to billions, obviously, is a reach.

“But if sunflower stars are as important as we think they are, this could be a really big lever to pull,” Gravem said. “If it can work, this will be a very important step to take.”

In the case of the stars identified by the Oregon Coast Aquarium crew, each was photographed, measured and returned to the soft seafloor below.

“This concentration of juvenile sunflower stars may be a precursor to the species’ recovery,” the aquarium said in a news release, “though only time will tell.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com