By QUINTON SMITH/YachatsNews.com

Take a look at your watch and count the seconds to 120.

One, two, three …. 61, 62, 63 … 118, 119, 120.

Two minutes.

It can be a really long time, says Doug Toomey, a professor at the University of Oregon who is leading the effort to install a seismic alarm system along the Oregon coast and in the Willamette Valley to give people a warning before an earthquake strikes.

Toomey says an early warning can be enough to help get you to safety in the event of an earthquake or headed out the door a bit earlier in case of a tsunami.

“Two minutes is actually a lot longer than you realize,” Toomey says. “You have a mental awareness of what’s about to happen … and then you can react.

“It can do quite a bit of good,” he says.

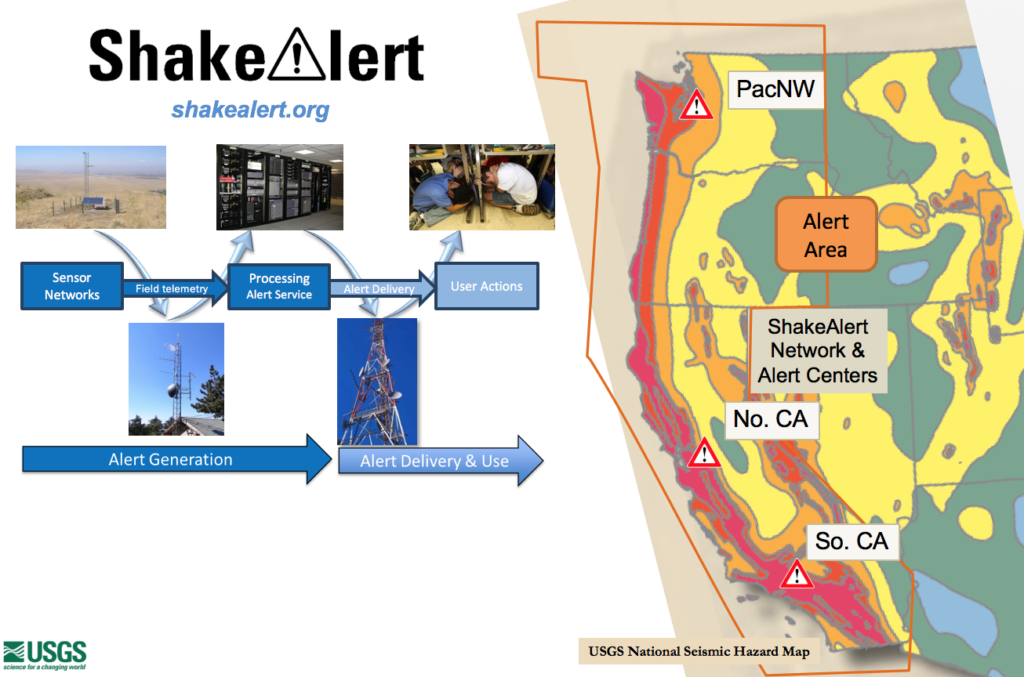

Toomey, the UO and the state of Oregon have been working with the U.S. Geological Survey and a consortium of colleges in California and Washington since 2014 to build an early-warning system called “ShakeAlert.” The goal is a three-state system of real-time monitoring stations that can warn the public seconds or minutes before an earthquake.

Part of the system is already operating in southern California, thrusting the program into the spotlight in early July when magnitude 6.4 and 7.1 earthquakes hit 100 miles east of Los Angeles.

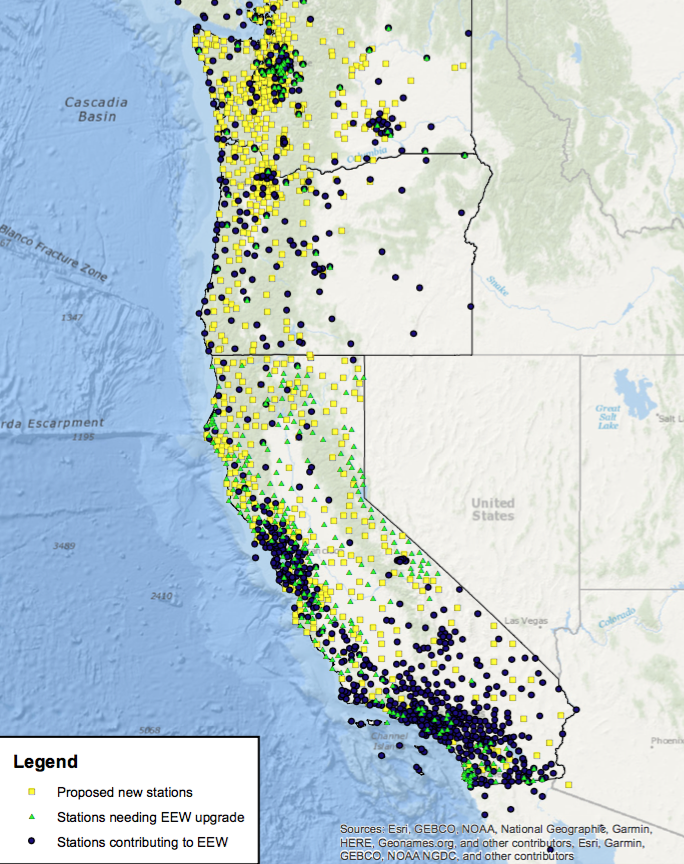

The plan is to have a total of 1,675 seismic stations up and running by 2023. There are 1,115 now, the majority in California. In Yachats, there is one adjacent to a city water reservoir on Horizon Hill Road.

Of the 238 planned in Oregon, 125 should be completed by Aug. 1. Although the partial system is capable of sending alerts to scientists and people in southern California, Toomey says in Oregon ShakeAlert needs 75 percent of its stations operating – it’s at 59 percent now — before it can be rolled out to the public.

Once Oregon builds the stations — they cost from $10,000 to $40,000 each — it turns over operation and maintenance to the USGS.

But the plan to build more stations in Oregon took a big hit in the final days of the 2019 Legislature early this month. As part of her statewide resiliency plan, Gov. Kate Brown had asked for $12 million to finish building Oregon’s seismic network and join Nevada and California in a wildfire alert program. The money was cut at the last minute by lawmakers.

“Oregon has been doing a spectacular job until recently,” Toomey said. “But something went sideways in this legislative session. I’m disappointed. But I don’t think it’s because of a lack of support for what we do.”

As if on cue, on Wednesday a magnitude 5.3 earthquake struck about 175 miles west of Reedsport, according to the USGS. The earthquake occurred at a depth of nearly 9 miles in the Blanco fracture zone, the USGS said, an area of frequent seismic activity but not indicative that a larger earthquake is imminent on the nearby Cascadia subduction zone.

Earthquake science and how ShakeAlert works

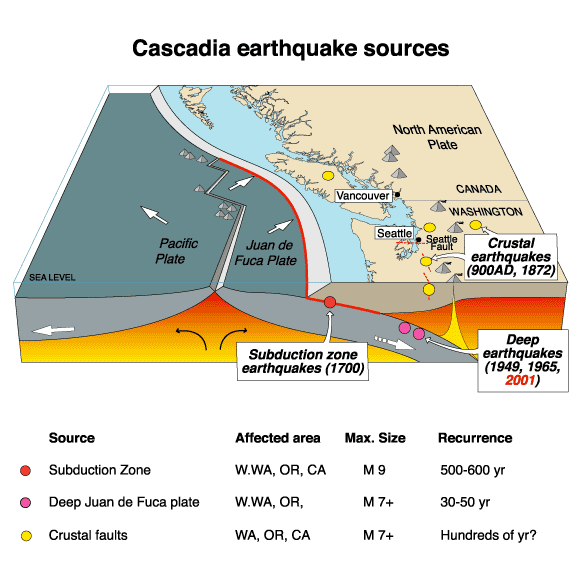

The biggest earthquake concern along the Oregon coast originates from the Cascadia subduction zone in the Pacific Ocean running from northern California to Canada.

During the next 30 years, according to the USGS, Oregon has a 10 percent chance of being hit by a magnitude 8 to 9 earthquake along the Cascadia zone. The last major Cascadia earthquake occurred in 1700, producing a tsunami that pushed water far inland and causing damage as far away as Japan.

Earthquakes create two types of energy — primary waves and secondary waves. Primary waves travel faster and usually don’t cause much shaking or destruction.

By detecting those initial primary waves, seismic sensors in the ShakeAlert system can measure the strength of a quake, relay the information to a central messaging center and create a warning – giving people warning of the stronger earthquake soon to follow.

Toomey said if the Cascadia Subduction Zone were to rupture from its southern end and move north like a zipper, people on parts of the coast and in the Portland area could have up to two minutes warning.

Toomey and the UO’s Oregon Hazards Lab where he works are already testing the ShakeAlert system with agencies such as the Eugene Water and Electric Board and the Oregon Department of Transportation. Those agencies are interested because an early warning could allow them to begin shutting down water or electrical systems or alerting motorists to hazards caused by earthquakes.

The goal – if and when ShakeAlert becomes fully operational – is to also link it to colleges and universities, schools, hospitals, and local emergency responders who already have notification systems.

Toomey has asked – and received permission – from the Central Lincoln People’s Utility District to place seismic equipment at some of its electrical substations along the coast stretching from Reedsport to Newport.

“Central Lincoln is a pretty forward-looking utility,” he said. “They said, “Sure, we’ll work with you.’”

Adding wildfires to the equation

The UO Hazards Lab has also added Oregon’s other growing emergency threat – wildfires – to its work by joining with two other universities to build a network of cameras in remote forests.

AlertWildfire is a consortium with the University of Nevada-Reno and the University of California San Diego to establish a network of state-of-the-art fire cameras to help firefighters and first responders discover, fight and monitor wildland fires.

Money in the governor’s budget – should it have been approved – would have paid to set up 85 WildfireAlert cameras in Oregon. Without state funds, Oregon’s program is now stalled.

“The fire camera program is essentially on hold,” said Leland O’Driscoll, program manager for the Oregon Hazard Lab. “That’s the program that really got hurt.”

The AlertWildfire system has 1,000 cameras already working in parts of California and Nevada, Toomey said, and should have full coverage of the state by the end of the year.

The public can log onto the AlertWildfire website, put in their location, choose cameras near them and then monitor any wildfires.

“We do this because we think the public needs to know about wildfires in their area,” Toomey said.

The camera system can also aid fire commanders in deploying resources to battle wildfires, he said, and then monitor them when the main fight is over.

The UO lab is also trying to work with the Oregon Department of Forestry and some private timberland owners in Coos and Douglas counties, which operate rudimentary camera systems on some of their timberlands.

What happened and what now?

The earthquake alert system is one of six “planks” in Brown’s overall plan – called Oregon Resiliency 2025 — for the state to better deal with catastrophic events. That money for earthquake and wildfire warnings were cut in the last days of the 2019 Legislature has left Toomey and other proponents of the system both mystified and disappointed.

Brown has appointed a “chief resiliency officer”, Mike Harryman, to oversee the state’s efforts. He declined to explain to YachatsNews.com what happened the money for the warning systems, referring questions to the governor’s media office.

“Legislators who didn’t include it in the legislatively approved budget are the ones who are best able to answer why they did not support it,” a governor spokeswoman, Kate Kondayen, said in an email.

Rep. Dave Gomberg, D-Lincoln City, who is a member of the so-called “Coastal Caucus” of legislators from the Oregon coast, said he never heard much about the issue.

“I did not hear anything about it,” he said. “It wasn’t raised to the Coastal Caucus.”

Rep. Cassie McKeown, D-North Bend, who represents the Yachats area, was on vacation and not available to comment.

But Gomberg was heavily involved in two other related issues during the session – cancelling a 1993 state law prohibiting building of public facilities like schools, hospitals and fire stations in tsunami zones, and putting the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries on a smaller, one-year budget. The agency, which had overspent its budget the past two bienniums, had proposed more adjustments to tsunami zones building requirements.

“We’re creating these zones but we’re not getting help getting out of the zone,” Gomberg said. “As the inundation line continues to creep east we’re running out of room to build.

“I don’t think we should build schools on the waterfront … but I don’t think communities should go bankrupt trying to find a place to build.”

Gomberg, Harryman and Toomey do not believe the tsunami issues were related to the money for the ShakeAlert system being denied.

Toomey says ShakeAlert supporters will keep trying to build the system, relying more on federal grants, possibly state bonds and bringing up the issue when the Legislature meets for a one-month session early next year.

O’Driscoll said federal grants should allow Oregon to install 29 more seismic stations in the next 12 months, bringing it close to but not meeting USGS’s 75 percent coverage threshold to go public. “We’re just not accelerating the program,” he said.

Toomey, however, expresses more frustration and disappointment.

“Along the West Coast, the only area falling behind and not receiving alerts will be the state of Oregon,” Toomey said. “We’re losing out on public safety, on federal investment and now getting even further behind to detect earthquakes and detect and suppress forest fires in our state.”