By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews.com

Barbara Schmaltz has weathered countless economic storms during the 37 years she’s owned the Chalet Restaurant & Bakery in Newport.

But she has never endured anything like the hiring issues now plaguing hospitality businesses up and down the Oregon coast.

“Not a single person has applied to work in our kitchen for weeks now,” Schmaltz said. “Summer is the season we count on to make enough to get us through the winter and it’s just not happening. It’s really scary.”

One obvious answer to what’s causing the severe shortage of workers is the enhanced unemployment benefits available to workers laid off in the immediate aftermath of the Covid-related shutdown that hit 13 months ago. Those benefits, which run through mid-September, allow workers who were earning at or slightly above minimum wage to now make just about as much – or more – by staying home.

But there are other factors in play, as well, which combine to present long-term challenges to a hospitality industry that makes up fully half of Lincoln County’s economy.

For one thing, extremely low housing availability makes it difficult for anyone outside the area to consider moving to the county, even if jobs are plentiful, said Erik Knoder, a regional economist for the Oregon Employment Department.

Also, the rising cost of available housing – whether renting or buying – makes it difficult for hospitality workers making $13 to $20 an hour to afford a place to live.

In addition, some potential workers are staying home to care for family members still recovering from COVID-19, Knoder said, while others can’t find the child care resources necessary to let them get back on the job.

“It’s a very tough situation for everyone,” Knoder said. “There are just no easy answers right now.”

Other sectors of the coastal economy are still being affected by the coronavirus-related slowdown, he said. Construction jobs, for instance, are still down 80 positions from where they were prior to March 2020 – despite what appears to be a building boom.

But leisure and hospitality positions have seen the bottom fall out, having shed 1,150 jobs in that same period.

“That’s where the big job loss was,” Knoder said. “And very little has changed since then.”

Hiring issues for lower-paying jobs

The problem is by no means limited to the coast.

Employers across Oregon are reporting similar shortages of people applying for lower-paying jobs according to a new paper published by the Oregon Employment Department and the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis.

A number of factors are now at work, the paper concludes, that make the current pandemic recovery very different from typical economic recoveries.

“These include a reduced or altered labor force due to COVID-related issues, transfer payments and benefits supporting households more during the pandemic, and rapid hiring during the re-opening period creating more intense competition among employers for workers,” according to the report by Josh Lehner and Gail Krumenauer.

Unemployment benefits are playing some role – but not the only one — in persuading potential workers to stay home, it said. The paper notes that the $300 per week enhanced federal benefits, on top of the average $370 per week state benefit, add up to an average payment of $670 per week.

That’s roughly the same as earning $16.75 per hour for someone working full time, the report found. For perspective, the report added that someone earning $670 per week year round would make $34,800 in gross earnings.

“By comparison, the median earnings for full-time workers in Oregon was $50,712,” the report states. “With ‘Now Hiring’ signs in many business windows and stronger wage offerings as employers compete for available workers, it’s unlikely that this benefit, in itself, is keeping a vast number of workers on the sidelines.”

A Census Bureau survey taken in late March showed that 6.3 million didn’t seek work because they had to care for a child, and 4.1 million said they feared contracting or spreading the virus.

But smaller companies that can’t offer pay and benefits as generous as larger companies have a tougher time.

“A shortage of talent is nothing new for small businesses, but the circumstances surrounding this shortage are entirely different,” Jill Chapman, a consultant with Insperity, a human resources provider, told The Associated Press.

Harder hit are businesses whose employees couldn’t work from home – grocery workers, retail of all types, restaurant and motel front desk workers – all of whom deal face-to-face with customers

Employers get more creative

Still, employers are going to unprecedented lengths in an effort to find the workers they’ll need to survive through the summer and into the fall.

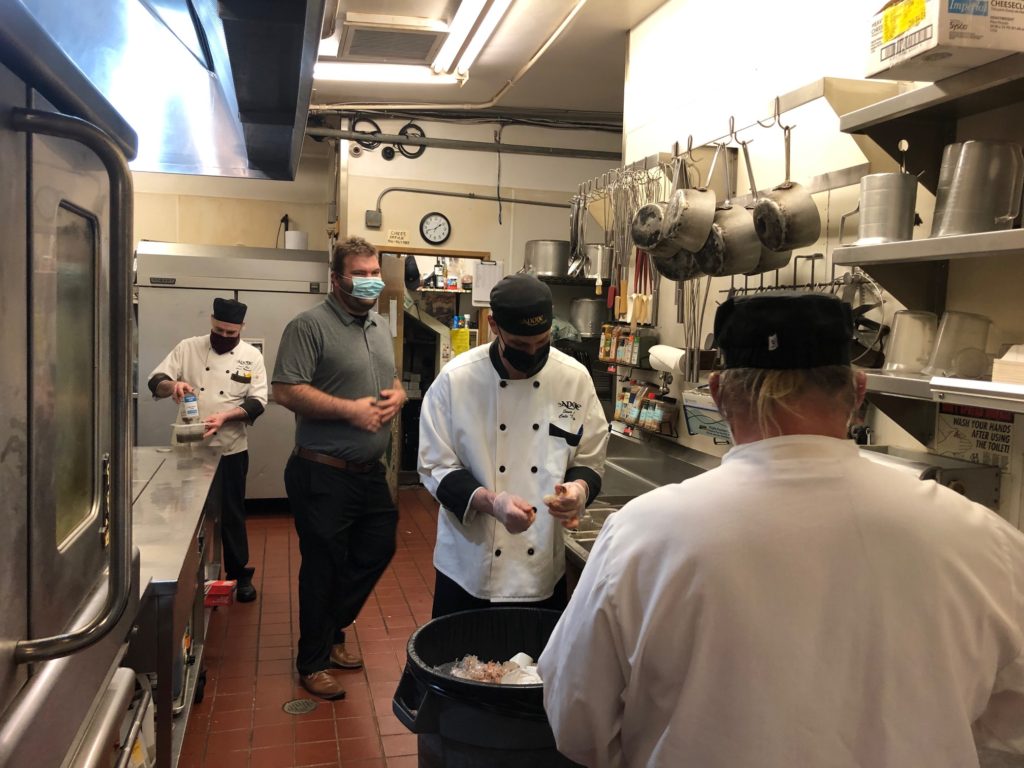

At The Adobe Motel and Restaurant in Yachats, general manager Anthony Muirhead has given up on the prospect of hiring anyone currently receiving unemployment benefits. So he’s looking instead at younger people – 16- to 21-year-olds – who weren’t working when the massive layoffs started a year ago.

He recently hired a culinary-school graduate who was working in Newport, but living in his car because he couldn’t find a place to live. Muirhead is letting his new cook live in a motel room until he can find permanent housing.

It’s not a sustainable situation, Muirhead said, because he can’t afford to let one of The Adobe’s regular rooms be taken out of circulation. He noted also that business is still booming, so much so that his reduced-level restaurant and housekeeping staff is working six days a week to meet demand.

“Obviously, this is only temporary,” he said. “We’re all realizing that if you don’t have a housing component as part of getting new employees, you’re not going to get them.”

Nearby, at the Overleaf Lodge and Fireside Motel, operator Drew Roslund is asking the City of Yachats to allow him to create a temporary RV area on the property to house seasonal workers.

He told City Council members that waiving current restrictions would allow him to offer RV spaces and hookups to people who travel around the country to work.

Other employers are also exploring novel solutions to a problem most didn’t even see coming as recently as a month ago.

At Ona Restaurant in Yachats, for instance, owner Michelle Korgan recently lost one of her best cooks to a higher-paying job in Alaska because he also lost his rental house. The new job, however, lasts only through July, and Korgan, is considering buying an RV to lure him back.

She is also offering bonuses to employees who work through the entire summer season.

“With tips even entry-level employees here are making $20 an hour,” she said. “But even with that, I’ve only been able to hire one person in the past month and a half, and I need at least six more people to open up more. What can I say? It’s grim.”

What’s perplexing to Korgan and others is that demand for services is incredibly high right now. The only reason her restaurant isn’t racking up peak-season revenues, she said, is state-mandated restrictions on indoor dining.

“I’m having to turn down requests for reservations because we have no space for them,” Korgan said. “These are definitely difficult times.”

On Friday, the Lincoln County School District announced it was having to suspend a nearly year-old weekend meal program for children because of a staffing shortage.

Hurting expansion plans

The worker shortage comes at a particularly tough time for Robert Anthony, who is smack in the middle of expanding his Luna Sea restaurant in Yachats with a new outlet in Seal Rock.

“It’s a nightmare,” he said. “I’m through the roof in terms of the business we’re doing, but limitations on staffing obviously play a big role in just what we can hope to offer the public.”

Since he actually owns two adjoining lots at the former Yuzen restaurant in Seal Rock, he is toying with the idea of acquiring a manufactured home sit on one of them.

“Like a lot of people, I’m trying to get creative,” Anthony said. “Some tents? A fire pit? A lot of young people might love that. Anything that will solve the problem is something I’ll be considering.”

In an ironic twist, the enhanced unemployment benefits that are at least partly responsible for keeping workers home are due to expire right around the time that coastal businesses would start laying people off as winter approaches.

“The whole thing is backward,” said Cyd Cannizzaro, manager of the Sylvia Beach Hotel in Newport.

In her own case, she added, “Just give me two more housekeepers. That’s all I ask. People are tired. They’re fried.”

Larger employers in the hospitality business are facing the same shortages.

“We are absolutely having similar problems,” said Pam Hickson, recruitment and compensation specialist at the Three Rivers Casino in Florence, which employs about 350.

“People left hospitality because there was no work, then the counties opened up all at once,” she said. “We’re all competing for the same workers.”

In the past, upwards of 50 prospective employees would show up at the casino’s big March job fair, Hickson said. The most recent one, held a week ago, drew two.

“The ballgame right now is retention,” she said. “What no one can afford is to lose the people they already have working.”

A recent Waldport hiring event sponsored by Vacasa, a vacation property-management company, attracted about a dozen potential housekeepers, most of them lacking experience. David Wilson, who oversees Vacasa operations on the central coast, said he hoped to find at least eight workers of the total 30 positions he’ll need to fill this summer.

Asked whether he’d ever seen the local labor market so tight, he answered flatly, “No.”

If there’s any upside to the unemployment benefits aspect roiling the coastal economy, Knoder, the state economist, pointed out that Lincoln County residents have received nearly $100 million in state and federal unemployment benefits since Covid started.

“That’s a lot of money that’s been pumped into the economy,” he said. “That’s also kept the labor force around so when conditions improve, workers will still be available to fill those spots.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com

Hospitality jobs, and especially those that depend on tips, have always been unsustainable and leveraged in the employer’s favor. The pandemic has just made clear the problems that are already there.