By MICHELLE KLAMPE/OSU News Service

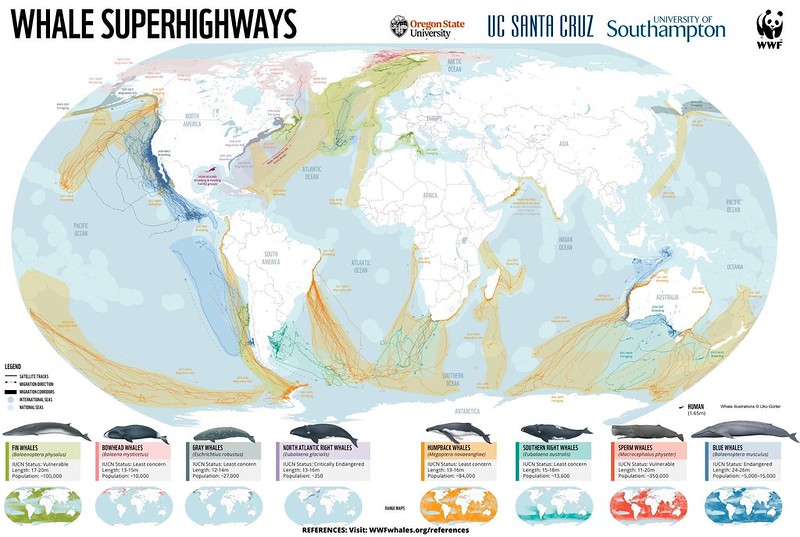

NEWPORT – A comprehensive new map and report tracking whale migrations around the globe highlights where they go in the high seas and the cumulative impacts the animals face from industrial fishing, ship strikes, pollution, habitat loss and climate change.

“Protecting Blue Corridors” was developed through collaborative analysis of 30 years of scientific data contributed by more than 50 research groups, with leading marine scientists from Oregon State University, the University of California, Santa Cruz, the University of Southampton and others.

The report, released by the World Wildlife Fund provides a visualization of the satellite tracks of 845 migratory whales worldwide. The report also outlines how whales are encountering multiple and growing threats in their critical ocean habitats – areas where they feed, mate, give birth and nurse their young – and along their migration superhighways, or blue corridors.

“Contributing years of data from Oregon State’s satellite tracking studies, pioneered by marine mammal researcher Bruce Mate, we see migrations across national and international waters creating conservation challenges for populations to recover,” said report co-author Daniel Palacios, endowed associate professor in whale habitats with OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport. Mate, now retired, is the institute’s former director.

The cumulative impacts of human activities are creating a hazardous and sometimes fatal obstacle course for the marine species, said Chris Johnson, the global lead for whale and dolphin conservation at WWF.

“The deadliest by far is entanglement in fishing gear – killing an estimated 300,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises each year. What’s worse, this is happening from the Arctic to the Antarctic,” he said.

Six out of the 13 great whale species are now classified as endangered or vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, even after decades of protection after commercial whaling. Among those populations most at risk is the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, a species that migrates between Canada and the United States. It is at its lowest point in 20 years – numbering only 336 individuals.

Palacios is an expert in the study of whale movements in relation to environmental conditions and human threats. His contribution to the report centered on the eastern Pacific Ocean.

“For a report of this nature, it was necessary to incorporate the data and expertise from many colleagues doing similar work in other parts of the world,” Palacios said. “For the first time, we were able to map whale migrations on a global scale and identify their superhighways.”

Protecting Blue Corridors calls for a new conservation approach to address mounting threats and to safeguard whales through enhanced cooperation on local, regional and international levels. Of particular urgency is engagement with the United Nations, which is set to finish negotiations on a new treaty for the high seas in March.

The benefits from protected blue corridors extend far beyond whales. Growing evidence shows the critical role whales play maintaining ocean health and the global climate – with one whale capturing the same amount of carbon as thousands of trees. The International Monetary Fund estimates the value of a single great whale at more than $2 million, which totals more than $1 trillion for the current global population of great whales.