By CHERYL ROMANO/YachatsNews.com

For decades, people who make their livings forecasting natural disasters have known an unsettling truth about the Pacific Northwest coastline — it’s poised to crumble into the sea.

It could happen in a few days or many years, depending on which scientists you follow. But they all seem to agree on one scenario — a shattering earthquake and resulting tsunami of up to 100 feet high will likely re-shape the coast as we know it.

“Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast.” That was the assessment of a Federal Emergency Management Agency executive quoted in the now-infamous article in The New Yorker magazine a few years ago that spurred a flurry of awareness.

Some 10 years before that, the city of Yachats launched an Emergency Preparedness Committee that has worked regularly to prepare for “The Big One.”

First, however, it’s useful to look at just what the threats are.

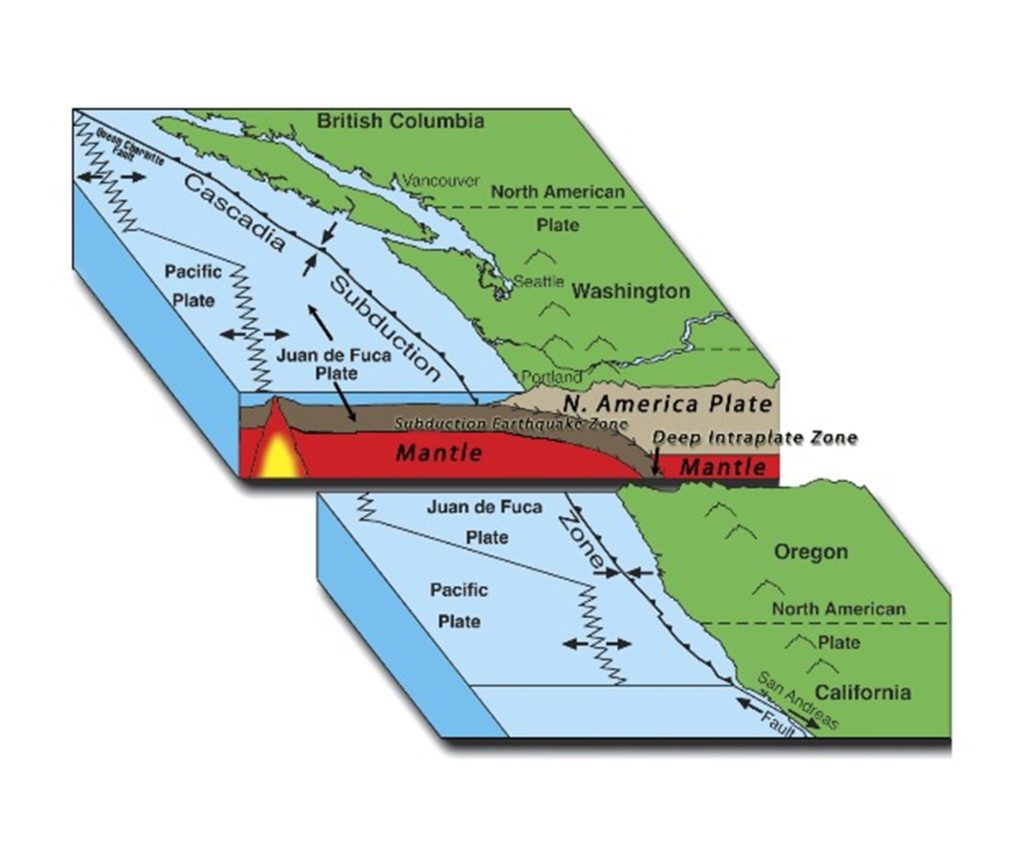

There’s a fault line that runs from northern California, past Oregon and Washington, up to British Columbia, called the Cascadia subduction zone. About 600 miles long, this giant fracture sits 70-100 miles offshore. On average, every 244 years the Cascadia subduction zone — that giant slab of the earth’s mantle called a tectonic plate — slides underneath another.

It usually happens over eons and humans barely notice it. When it occurs fast, the violence can rearrange continents and oceans, with epic earthquakes triggering disastrous tsunami. The last major event happened 321 years ago — again, the average is every 244 years.

Victim or survivor?

“So, are you ready? Will you be a victim or a survivor?”

That’s the question posed by Jim Kusz in his annual course at Oregon Coast Community College titled “Disaster Preparedness in the Pacific Northwest.” A retired captain with North Lincoln Fire & Rescue District in Lincoln City, Kusz has been teaching the popular class for six years.

“Attendance spiked early on, after word spread about the article in The New Yorker,” said Dave Price, the college’s vice president of engagement and entrepreneurship.

Although it was the first year that a $15 fee was charged and the first year for an online class via Zoom, it was “our best-attended in years,” said Price.

Victims of another type of disaster — wildfires — benefited from the tuition fees. At Kusz’s behest, $1,000 in class fees were donated to the Echo Mountain Fire relief fund for Otis fire victims.

“The wildland fire is going to get us long before the tsunami will,” Kusz says.

The devastating wildfires that scorched Oregon and California last year were grim reminders of how quickly life and property can be destroyed. And let’s not forget about COVID-19 — the only pandemic in contemporary American history has upended what used to be “normal” life.

For Kusz, all these factors mean “it’s important to empower people. Whether it’s earthquake or tsunami, wildfires or pandemic, my key message is, ‘Don’t be paranoid — be prepared’.”

Why is preparation so vital?

“Because nobody else is going to do it for you,” Kusz says. “Think about the roads sliding into the ocean, fires breaking out all over … No mutual aid will respond, no FEMA trailers will roll in to save the day.”

Help, if any arrives, he says, will be “weeks, perhaps months out, all communications will be overwhelmed, thousands will be homeless and food, water and shelter will be scarce.” While Kusz jokes about a “zombie apocalypse,” he isn’t kidding about the apocalypse part.

It sounds like a disaster movie, only the scenario isn’t fictional.

The Oregon Office of Emergency Management soberly has this to say on its website: “The Cascadia Subduction Zone has not produced an earthquake since 1700 and is building up pressure … Currently, scientists are predicting that there is about a 37 percent chance that a megathrust earthquake of 7.1+ magnitude in this fault zone will occur in the next 50 years … With the current preparedness levels of Oregon, we can anticipate being without services and assistance for at least two weeks.”

That means no electricity, no water, no rescue units, no firefighting, no medical services, no ready food supply — and in the Yachats area in particular, probably no access to nearby towns. It’s likely that bridges will snap, roads will disappear, hillsides will flatten and homes will wash away or fall into the earth.

Preparing to be a survivor

What does preparation look like? At the very least, experts from FEMA to the American Red Cross to people like Kusz urge everyone to have a “go bag” in their home and in their car. The contents (as many as possible in a backpack) should include items like these:

- Water and water purification kit

- Non-perishable foods like energy bars

- Copies of documents such as insurance policies and passports (or digital copies on a thumb drive)

- Flashlight with spare batteries

- Portable radio

- “Space blanket” and extra, wet-weather clothing

- Sturdy boots and gloves

- Cash

- Can opener (non-electric) and Swiss Army-type pocketknife

- First Aid kit

- Medications

- Pet food and supplies

- Duct tape and plastic sheeting or large plastic bags to make a shelter.

- Waterproof matches

Of course, individual needs will vary. But the point, as experts hammer, is to be ready.

What if the ground shakes you out of sleep at 3 a.m.? What if your partner is shopping in Newport when a tsunami rolls in and you’re at home with the emergency supplies? What if a wildfire erupts in the woods around your home?

All the “what if’s?” have to be answered when the “when” occurs.

No bridges, no helicopters, no Red Cross

People need to understand the risks and have a plan, including a communication plan to help support each other in the aftermath of a severe event, says Tracy Crews, chair of the city of Yachats’ Emergency Preparedness Committee.

“There will be no bridges, no helicopters rescuing us, no Red Cross, no cell phone service; it’s hard for people to wrap their brains around,” Crews says.

Preparing for such disasters takes committee members out into the community every three months to check on the two supply containers sitting high on hillsides. Inside the shipping containers are food, blankets, first aid kits, sleeping bags, water purification devices and body bags —yes, body bags.

A goal for this year is to establish another container site and make an official evacuation site at the new Yachats Rural Fire Protection District station on the north edge of town.

On a recent cold, drizzly morning, Crews and several committee members laid out the supplies on tarps to check expiration dates and conditions. The fact that many items are in cardboard boxes dampened by the rain underscored another goal — to get the supplies secured in watertight plastic containers.

Among the committee’s crew that morning was city of Yachats safety co-leader Kimmie Jackson, who shares that title with Kevin Kentta of the Public Works department. A member of the committee since 2012 and also the city’s deputy recorder, Jackson feels that many fulltime residents — and most part-time visitors — are “not as prepared as they may think.”

“If there was a way to receive donations and have volunteers put together ‘go bags’ it would be a good start,” Jackson said.

Meanwhile, she advises, “Start putting together your emergency bag — even if you buy just one or two items at a time to start.”

Drinking wine, watching the wave come in

Disaster prep is a big planning job, but not everyone takes the threat to heart. When “The Big One” hits, a number of Yachats residents have told Crews that they will “Sit on my deck drinking wine, watching the wave come in.”

To that, she counters, “But what if you don’t die? If you’re on the west side of the highway and you drown in the tsunami it’ll be fairly quick — but what if you’re up on the hill and your house pancakes?”

Yachats has no warning siren. “Our warning will be the actual shaking of the earth,” Crews said.

And the blue “Leaving Tsunami Zone” signs painted on roadways in Yachats and up and down the coast?

I certainly wouldn’t stop when you get to that blue sign — I would keep going,” she advised. There is a Yachats hazard map available on the city website outlining the areas of potential danger and safety.

Crews’ job as Oregon Sea Grant marine education manager at Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport has given her a lot of experience with getting prepared. She’s involved with the South Beach tsunami cache group, formed originally with seven state and federal agencies, plus Oregon State University researchers who study tsunamis and earthquakes. And as a Yachats resident, she knows what the potential perils are for the city.

“We live in a small, isolated community and will likely be cut off when bridges fail,” she said. “Having at least several weeks of food for ourselves and our pets will be needed, as there are limited supplies in the city-managed caches.”

Like others knowledgeable about preparation, she recommends keeping a backpack with a three-day supply of food, water and medical supplies in your vehicle.

On a local level, she urges residents to help spread the word about disaster preparation to neighbors, and encourage them to stockpile supplies. She also suggests these actions:

- If your home isn’t bolted to the foundation, consider having it done.

- Think about adding earthquake insurance to your homeowner’s policy; it isn’t standard hazard coverage.

- Sign up for the Lincoln County alerts program to get emergency emails, texts and phone calls.

- Consider volunteering with the Yachats Emergency Preparedness Committee.

“It’s really up to each of us to prepare ourselves and those that we love,” said Crews. “We need to understand the risks and have a plan.”