By MIRANDA CYR/The Eugene Register-Guard

EUGENE — The University of Oregon’s newly launched earthquake research center will bring together 16 institutions in the effort of researching earthquakes, their risks and impacts, and, in particular, “The Big One.”

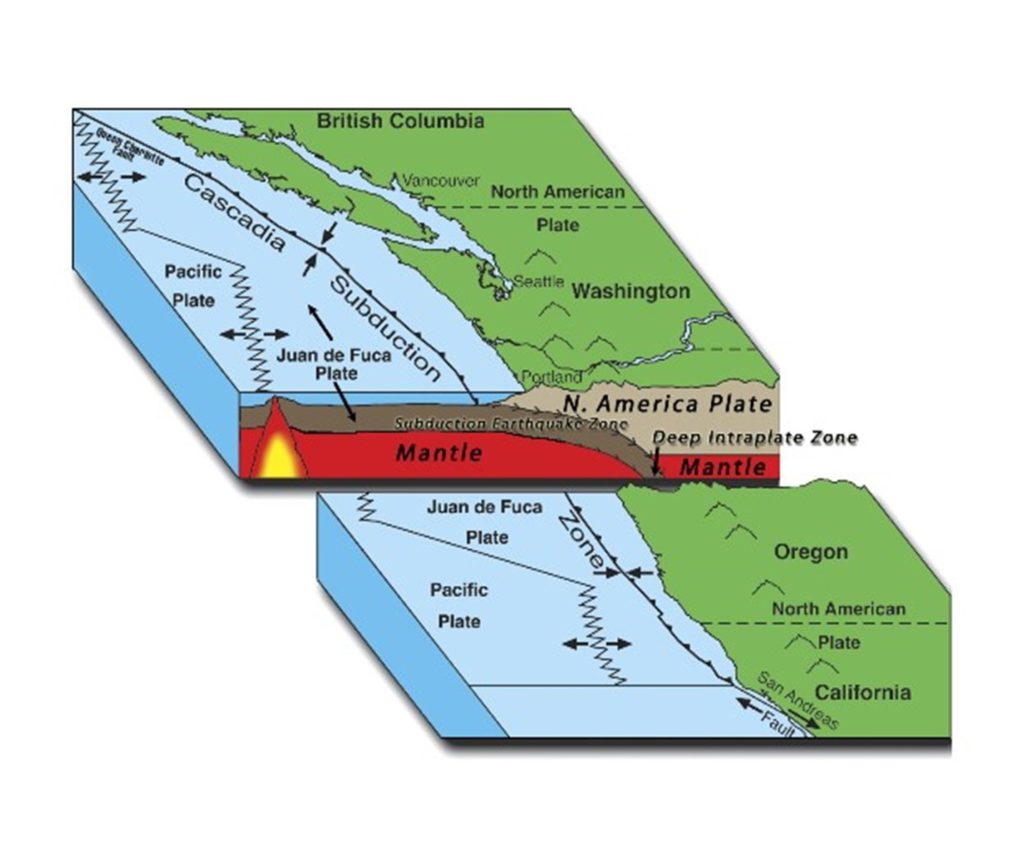

The Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center – to be known by the acronym CRESCENT — will be the first center of its kind in the nation focused on earthquakes at subduction zones, where one tectonic plate slides beneath another.

There are other similar earthquake research centers around the nation, such as the Southern California Earthquake Center at Caltech, but CRESCENT will focus solely on the Cascadia subduction zone, an offshore tectonic plate boundary that stretches more than 1,000 kilometers from southern British Columbia to northern California.

The 1700 Great Cascadia earthquake was the most recent big quake in the zone. If one similar to it were to occur now, researchers say it would have significant impacts: 10,000 casualties, thousands of buildings destroyed and thousands of households displaced. Depending on location, it could take weeks to years to restore basic utilities.

CRESCENT will not push for preparation or infrastructure readiness, said Diego Melgar Moctezuma, associate professor of earth sciences at UO, who has been named the center’s director.

The scientists will research when a significant earthquake might occur, what magnitude it could be, how long shaking could go on, how frequently these earthquakes could occur, as well as questions about tsunamis on the West Coast.

Faculty and staff will research and publish to inform agencies on how to adjust building codes, for example, said Melgar Moctezuma.

“Those are really important things to know, because that informs the building code,” he said. “You can’t be infinitely strict, because that would mean buildings to be extremely expensive. The building codes need to be just right. They need to be tough enough for the worst earthquakes that we can expect in a region.”

Shaking up the field

Creation of the center has been in the works since around the start of the Covid pandemic, according to Melgar Moctezuma.

Interest in earthquake science and seismology has grown significantly in the Pacific Northwest, as indicated in part by the growth of such departments in nearby public universities, he said. He and his colleagues saw a spike in seismologists working on much of the same research, but there was no organization and not enough collaboration.

Melgar Moctezuma said many of his colleagues came from the Southern California Earthquake Center and know the value of a collaborative research center and how useful it could be in the Pacific Northwest.

Then, in 2021, the National Science Foundation announced a solicitation for geohazard research at university-based centers.

“It was just an obvious thing to do,” Melgar Moctezuma said. “It was a little bit lucky − a consequence of the money being made available by the federal government, but also of enough people being here that care about those things.”

CRESCENT was funded by a $15 million grant through the National Science Foundation:

The center will also push for more diversity in the earth sciences field, which has the “worst track record” of all STEM fields, with low proportions of women, Latinx and Black professionals, Melgar Moctezuma said.

The 16 participating institutes have plans for student learning and experience opportunities at the high school, undergraduate and graduate levels.

The three “pillars” of CRESCENT:

Science: conduct research

Partnerships and applications: connect with state geological surveys and other federal, state, county and city agencies.

Geoscience education and inclusion: seek to diversify the field of seismology by providing more opportunities for young people to get involved and learn about earthquake science.