By DANA TIMS/YachatsNews.com

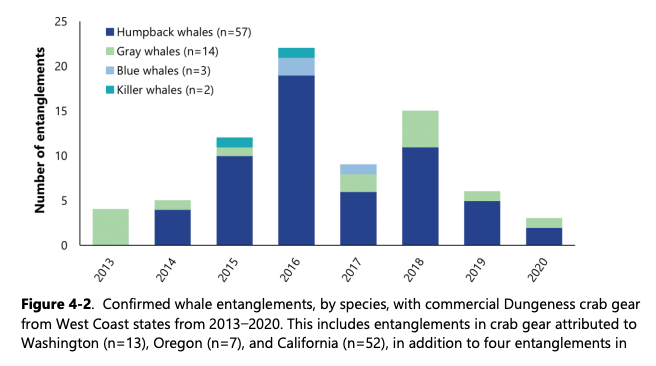

Since 2013, only seven humpback whales are known to have become tangled with commercial crabbing gear in Oregon’s coastal waters.

The number seems small, but humpbacks are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. So unless Oregon creates a plan to monitor and limit future entanglements, the federal government could move to shut down the state’s multi-million-dollar Dungeness crab industry.

Now, however, after four years of collaboration involving the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, commercial crabbing interests and environmental groups, that plan is almost finished and on track to be submitted this winter for federal approval.

“There is a lot at stake here and this is a problem we really need to solve,” said Caren Braby, who manages the ODFW’s marine resources program. “The alternative of closing the fishery forever is a really dire prospect.”

A number of the proposed plan’s key elements have already been implemented on a three-year trial basis, she said. All those steps involve trying to keep commercial crab boats as far as possible from waters where humpback whales are known to be swimming. Those measures include, for instance, reducing the number of crab pots that can be deployed at certain times of the year and, knowing that humpbacks tend to inhabit deep waters, setting maximum depths at which pots can be set.

The goal now is to “dot all of the i’s” in the plan, Braby said, and get it ready to submit to federal authorities – in this case, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — sometime this winter.

Such approval would grant the “incidental take permit” the state and commercial crabbers are seeking. The Endangered Species Act prohibits the “take” of listed species through direct harm or habitat destruction. Permit holders can thus proceed with an activity that is legal in all other respects, but that results in the “incidental” taking of a listed species.

“This is a request for a 20-year permit with a strong emphasis on adaptive management,” Braby told members of the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission during a virtual presentation Friday. “This will ensure that the plan can change as it needs to.”

The plan does not address entanglements with gray whales since that species has recovered to the point it is no longer listed under the Endangered Species Act. Blue whales and leatherback sea turtles are mentioned in the plan because they do have ESA listings. However, neither of those species has been reported to have been tangled in crab gear in waters off the Oregon coast.

Plan has industry support

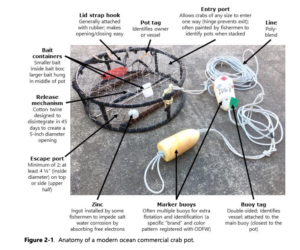

Entanglements occur when humpback whales, migrating off the coast, get fouled up in the lines, nets or traps deployed by commercial crab boats. Since these incidents almost always occur in deep waters, it’s often not immediately evident to the respective boat that an entanglement has even occurred.

In addition, whales can end up dragging the equipment that snared them for long distances, and the entanglement, if spotted at all, may not make clear in whose waters the incident originally took place. Braby told commissioners that some entanglements are likely never observed at all.

Of the 57 total entanglements of humpback whales along the entire West Coast from 2013 through 2020, only seven are known to have occurred in Oregon waters. Of those, two were in 2015, with one each in 2014, 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Tim Nototny, communications manager for the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission, said he and virtually all commercial crabbing interests support moving ahead with all elements of the plan.

“The bottom line is, industry doesn’t want to entangle whales,” he said. “It’s not good for whales, it’s not good for the environment and it’s not good for the fishery.”

The state’s crab industry is the most valuable single species commercial fishery in Oregon, according to state statistics. More than 16 million pounds of crab have been harvested in each of the past 25 seasons.

“Over the past 10 years, commercial crabbing has injected $1 billion into Oregon’s economy,” Novotny said. “So this isn’t important just for fishermen. It’s important for every Oregonian to see us succeed.”

Commissioners, during their virtual presentation Friday, did get some pushback from some environmental advocates.

Ben Enticknap, a campaign manager and senior scientist at Portland-based Oceana, said that climate change is driving a change in animal behavior, and that the proposed plan’s timeframe should be reduced from 20 years to a shorter duration to provide more flexibility to address those changes.

Francine Kershaw, a staff scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Fund, called the plan “a positive step forward,” but said additional steps are needed to reduce risk to whales. Most significantly, she added, sufficient funding must be sought to ensure that the plan’s various elements are enforced.

Braby said that a five-year horizon would be ideal, but given that it has taken more than three years just to get this far, a 20-year window may be the best one available.

“What we submit this winter allows for modification and adaption to the degree we needed it,” she said. “If we have to, we’ll reinitiate it and start all over again.”

- Dana Tims is an Oregon freelance writer who contributes regularly to YachatsNews.com. He can be reached at DanaTims24@gmail.com