Kama Almasi of Yachats has lived in Japan, been a paralegal in Seattle, taught college in Wisconsin – and this spring taught math to middle school students in Toledo.

But starting in August, Almasi will spend 11 months in Washington, D.C. as one of 15 Albert Einstein Distinguished Education Fellows. The 30-year-old program is sponsored by five federal agencies to put science, technology, engineering and math (called STEM) teachers in touch with national education programs and policymakers.

Her goal is to learn how to better involve, instruct and challenge minority and lower-income students in the sciences.

Almasi will work in the Youth and Education in Science office at the U.S. Geological Survey headquarters in the Washington suburb of Reston, Va. She plans to focus on diversity and inclusion on USGS projects, bring the agency’s extensive data into classrooms, and build support for STEM programs.

That includes working on “next generation” science standards for public education, Almasi said, and working on ways to bring more diversity to STEM instruction.

“Our teaching isn’t equitable,” she said.

Of course, the coronavirus pandemic has changed some procedures and practices of how Almasi will work during her fellowship. She has already met online with other Einstein Fellows, plans to meet everyone in person in August, but has heard from the USGS that she will have to work remotely in the beginning.

“We haven’t heard much, but we think COVID-19 will probably change the focus of our work a little bit to incorporate remote education,” Almasi said. “And many of us already planned to work on social justice and equity issues, so the social unrest around racism has just made us that much more committed.”

Teacher is always learning

Almasi’s educational journey isn’t a straight line.

“I can’t seem to stop learning,” she says.

Almasi was an Asian Studies major in college, although while growing up in Seattle she hoped to be a marine biologist. She worked as a paralegal, studied at the University of Washington before entering a doctoral program at the University of California-Davis. She earned her PhD in ecology in 1998 and headed to Newport for post-graduate work at the Hatfield Marine Science Center. Then came a college teaching stint in Wisconsin.

In 2007 Almasi and her husband, Rex Smith, decided to return to family property near the mouth of Tenmile Creek.

She started volunteering at Crestview Heights School, where her son, Koa, was a second-grader. Almasi applied for a teacher’s aide job, but the school district thought with her background she could get a provisional Oregon teaching license.

She started teaching math at Waldport High School in 2011 and in two years got her regular teaching license.

Almasi left Waldport High in 2017 to help the Lincoln County School District spread science, technology engineering and math instruction into elementary schools and help redesign sixth-grade educational programs for the district’s annual outdoor school.

She returned to the classroom this year to teach seventh- and eighth-grade math at Toledo.

Almasi is the second Yachats educator to be selected for the prestigious fellowship. Ruth McDonald, now retired, participated in the program in 2007 and encouraged Almasi to seek a nomination.

During the last few years, Almasi said, she became more and more focused on how to improve science education for students of color and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

“We’re doing really badly with elementary school science,” she said. And that’s why her emphasis on improving the diversity of students in STEM programs, which matches what the USGS wants her to focus on.

“They want my expertise to help in fixing their education units … and to improve equity in STEM,” Almasi said.

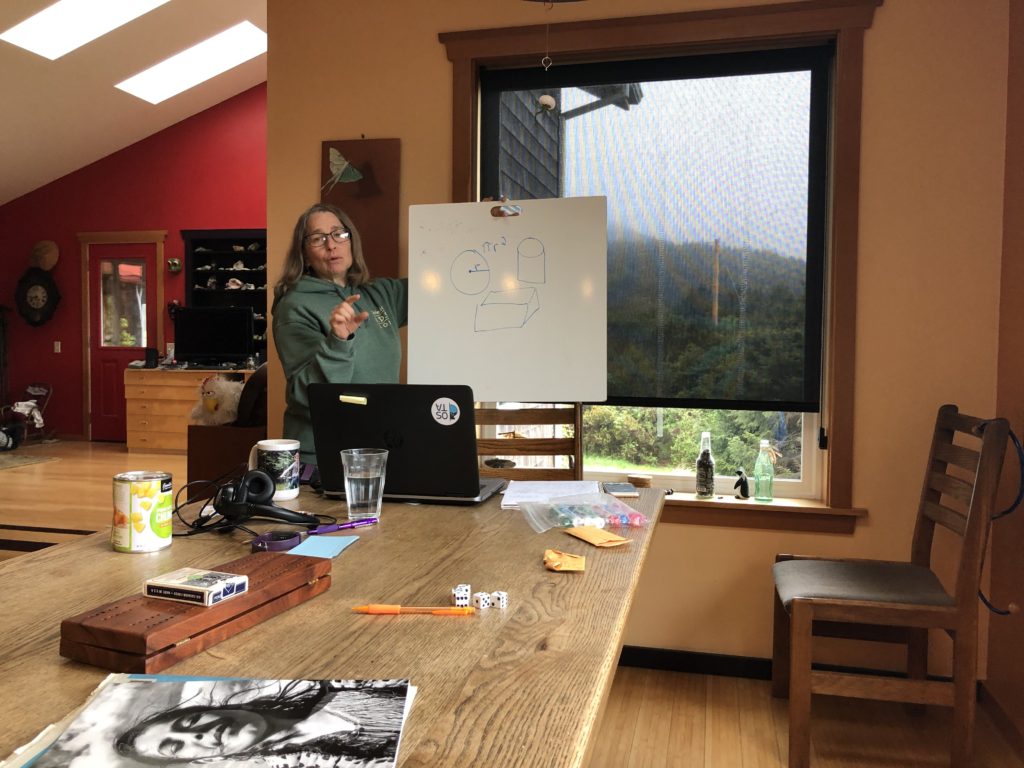

That ability to adapt and change is being tested daily during the coronavirus pandemic and since mid March the closure of all Oregon schools. Now that the district has begun offering online instruction, Almasi teaches math classes via a video platform from her dining room table or home office, and then follows up with independent lessons or written packets of information for students not yet connected to the internet.

Almasi says it’s a big change for teachers used to being able to see students in the classroom – to see faces, to interact, to get a sense of whether they’re understanding the instruction.

“It’s a big challenge. It’s hard,” she said. “But it’s also an opportunity” to see if other forms of instruction can work for some students.